Composer BRIAN TYLER has been “wowing” us for years with his scoring, instrumentations, and orchestrations. The composer and conductor of over 70 films, his work speaks for itself: Rambo: Last Blood, Iron Man 3, Avengers: Age of Ultron, Thor: Dark World, Crazy Rich Asians, Eagle Eye, The Expendables franchise and so much more, including the film logo music for Universal Pictures, the theme music for the NFL on ESPN, the U.S. Open Championships, and the Marvel Studios logo in 2014. While picking up multiple Emmy nominations over the past few years on several different series, for the past two seasons, and now into a third, BRIAN TYLER has brought the American Old West to life scoring Taylor Sheridan’s hit television series, YELLOWSTONE.

One of Tyler’s greatest strengths is that as a multi-instrumentalist and orchestral conductor, skilled in playing piano, guitar, drums, bass, cello, world percussion, guitarviol, charango, and bouzouki, amongst others, he has the unique ability to bring a multiplicity of different strings and woodwinds in varying ranges into the score of YELLOWSTONE, creating a defining tone that carries throughout the series but then is uniquely emotionally punctuated to a moment in the story, a character or an event.

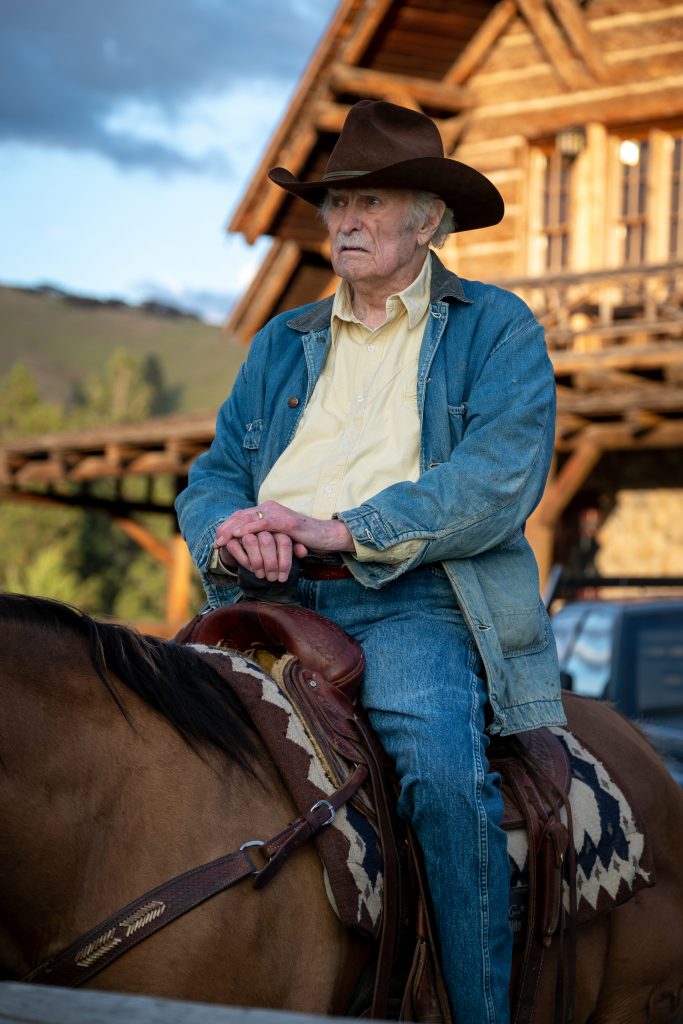

For the uninitiated into the world of YELLOWSTONE, this is the ongoing saga of the Dutton family, led by John Dutton, who controls the largest contiguous ranch in the United States. Set in present-day, YELLOWSTONE boasts the values of the Old West where men still wear white hats and black hats, but there is a lot of grey to be found in between thanks to the Dutton ranch being under constant attack from land developers of various ilk, an Indian reservation, and the United States of America’s first national park. Led by Academy Award winner Kevin Costner, YELLOWSTONE boasts an extraordinary ensemble cast including Wes Bentley, Kelly Reilly, Luke Grimes, Cole Hauser, Gil Birmingham and in Season Two Episode Ten, a special guest appearance by Dabney Coleman in a flashback as John Dutton’s father nearing the end of his life.

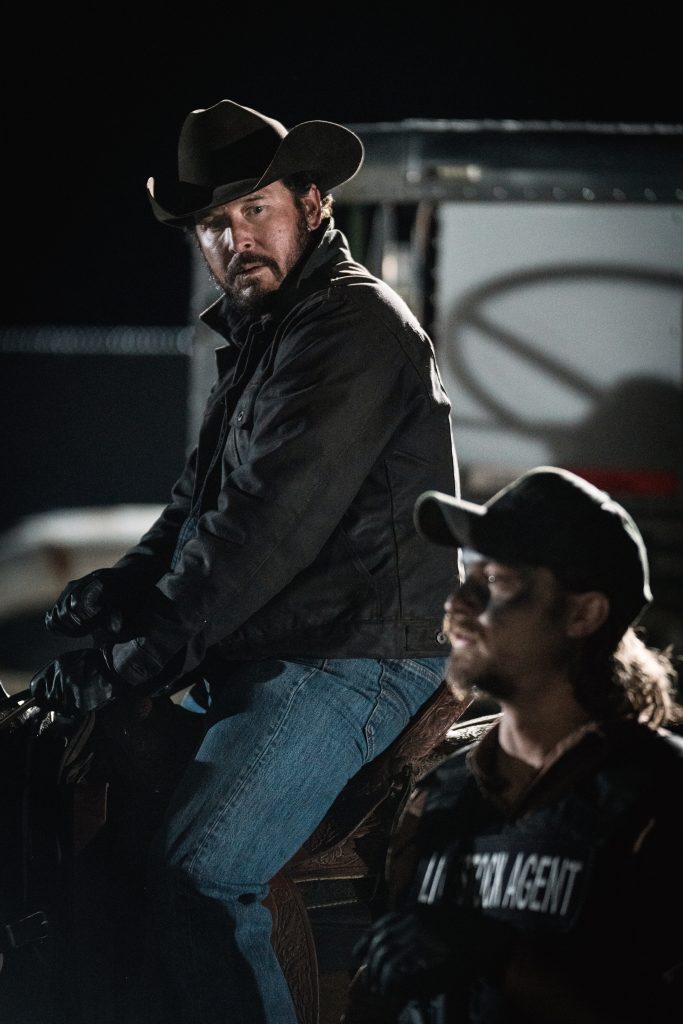

Season Two of YELLOWSTONE took us on an emotional rollercoaster ride as John Dutton was forced to joins forces with territorial enemies in order to not only save his ranch and the ranching way of life but save his grandson who was kidnapped by Malcolm Beck, an enemy to all. In a climactic nailbiting season finale, Sins of the Father focuses on the feud with Beck coming to a head as John and his family, together with local land management and law enforcement, developer Dan Jenkins, and tribal leader Thoma Rainwater put aside their differences to save a child. A tearjerker to be sure, much of the story and emotion of this episode comes from and through the music. It is this episode that BRIAN TYLER has submitted for Emmy consideration for Outstanding Music Composition For A Drama Series (Original Dramatic Score)

Always a joy to speak with BRIAN TYLER, especially about YELLOWSTONE, of which we are in agreement should be an annual get together “forever”, this year began on a more somber note thanks to the pandemic lockdown which found Tyler “in isolation.” Finding it “fantastic in terms of the creative process, I miss people and doing concerts and things like that. But, it’s been interesting. I had a bunch of projects, some of them went right up to the finish line, right up to when it all went down. Actually, I was right about to conduct a score and that got pushed, obviously, until after all of this. I did a movie, Clouds, which just finished up and that was all me playing all the instruments. YELLOWSTONE has been going and that’s been amazing. Then, of course, Those Who Wish Me Dead with Taylor [Sheridan], so it’s been quite a run.”

Briefly catching up on Rambo: Last Blood, which Tyler considers to be “[S]pecial because it’s so emotional and kind of epic at the same time”, part of what makes it special is that “Sly is a music guy for sure. He loves to feel. He always wants it really emotional, which is right up my alley”. The same can also be said of BRIAN TYLER and his collaboration with writer/director Taylor Sheridan, the formidable force behind YELLOWSTONE. Tyler and Sheridan are so in tune with the multi-dimensional way to tell a story and the importance of music in storytelling, that it’s impossible to imagine anyone but BRIAN TYLER composing for YELLOWSTONE.

Digging in deep once again in this exclusive interview on the show and the musical arch, we explored the musical nuance not only of Season Two, but specifically Episode Ten, as Tyler goes against the expected grain with his composition and instrumentation evoking palpable emotion.

Brian, I am thrilled that you’re tossing your hat back into the For Your Consideration Emmy ring again this year for YELLOWSTONE, Season Two, and most particularly for your submission episode of Sins of the Father the Season Two finale.

Yes! Yes. Sins of the Father.

I cried my eyes out when I watched it last summer and then I actually rewatched the whole season again over the weekend in anticipation of speaking with you this week, and cried again with Episode Ten. I am so happy that you chose that episode to submit.

It’s so powerful. When they’re saddling up; there’s so many scenes that stick out; that riff going into certain moments. You have this heart wrenching overarching thing with a child and how they band together. And this idea with the music, instead of doing something that’s militaristic, doing these adagios that are just very slow and moving, as opposed to what normally would be done in that, which is kind of pumping up the adrenaline. It’s not that. That’s there naturally, so you want to feel these scenes with your heart.

Almost the entire episode is adagio, however, there are moments where you bring the tempo up a bit. You never quite hit allegro. You’re kind of at the andante stage. So beautiful Once again, I love your instrumentation. What you do in composing with the instrumentation and then tying your motifs and tying your score in with the needle drops is so well done.

That’s an important part of it. That’s why we all kind of work together on that. Andrea von Foerster is the music supervisor. The music has always gone on as a unit and even the instrumentation and whatnot and kind of the idea of doing these pieces in the score that have their own flavor but can tie it together. I’m writing in the style of doing laments. You know? It’s the kind of music that’s reflective, like the style of Irish laments and things like that, where you’re reflecting on the loss or the hope or these things. It’s all kind of just out of reach, which gives you a very melancholy tone. YELLOWSTONE is such an interesting peek at the psychology of being either trapped between decisions that are impossible or kind of a peek into the darkness that even surrounds the side that you would hope would have the upper hand. Those shades of gray I think are so interesting musically and emotionally than kind of the simple good-bad and nothing in between.

If you saw my notes for Episode Ten you would see that I have “lament, woeful, sorrowful, melancholy” all over the pages.

You nailed it! There’s something just so interesting with that, and if you kind of have a window into that and you get to feel it through another vehicle, like either theater or literature or a movie or whatever, or YELLOWSTONE or music, it’s cathartic. Because we experience those emotions, it’s kind of like the catharsis comes from feeling the anonymity with the characters. The music can really bring that home. It can also steer it in a completely different direction. You can imagine when one of Rainwater’s tribal members is painting the horse and Rip is getting on it, if it was doing this kind of march into battle music, how different the entire tone of the entire show would have been, just from that scene. Completely different.

Just before that scene, at the 31-minute mark, you have a very woeful cello as it’s decided Rip is going to draw the fire so that Dutton and Jamie can go get Tate. We’re shifting scenes into the horse, the war paint, and Rip, and you bring in the piano very soft, very slow, and then you bring strings up. At the 35:27 mark, boom, you interlace the YELLOWSTONE theme motif but slow down the tempo. Then all hell breaks loose and the music is pounding. It’s fast. It’s moving. It’s pulsating. It’s palpable. Just that one segment, a seven-minute segment, is so incredibly constructed, Brian. You take it all the way up into this rapid crescendo and then at 37:08, boom, a decrescendo down to just the simple cello again.

Yep. All the way down. That’s the kind of the soul of the episode. In fact, that hearkens all the way back to the very opening scene of Episode One of Season One where you hear that with a horse and the car accident and Dutton, John Dutton, talking to the horse. That kind of really spare cello that’s become such a voice, the voice of the Duttons, and now the extended family that they have. It feels so plaintiff and melancholy. There’s these victories, but they’re pyrrhic victories. They’re never quite complete. I think it speaks to where you’re not just going to have everyone smiling and jumping up and down. It’s not that kind of thing. It’s really a victory to get to the next day, but maybe you lost something along the way, too, or you had to do something you didn’t want to do. They had to do these things where they’re not happy about it and it takes a little part of your soul because you had to kill somebody, some crazy thing that kind of eats away at you, just so you can keep the family together and keep going and surviving It’s a give and take. That’s what I was saying about why dwelling in the shades of gray is so interesting. That’s why I kind of relate this story more to a Shakespearean tragedy, like King Lear and things like that, and it’s why that kind of thing has always been interesting, all the way back to the Iliad and the Odyssey or even before. The greats of storytelling kind of dwell in the complicated, the in-between, the emotions that are in between the major emotions.

It’s funny because after we get that, the crescendo, the decrescendo, and John has shot Beck once, twice, three times, we have a constant – and I love this – a constant, very, very low modulated lamentation with strings. I don’t think you were using cello there.

Boom, boom, boom! Yeah. It’s a bass. The low C-string of the cello couldn’t go that low. Not often do you have a bass solo! There’s a certain type of resonance, too. It sounds very dark.

It felt like death.

A lot of things that would normally be, for instance, violin solos, I have to do on viola in YELLOWSTONE. I kind of go one instrument down. The woodwinds tend to be the contras. There’s contrabassoon, the contrabass clarinet. There is also, when it’s trombone, it’s bass trombone. Everything has a bit of a lower notch to it than normal. It creates that kind of darker tonality.

I definitely agree. There is nothing high pitched. I think the highest pitch thing we hear, especially in Episode Ten, is back when Kayce is ready to take off and he tells Monica, “I’m going to get him [their son] back,” and she goes, “Promise me, you’ll kill him,” and then I get my beloved Bernard Herrmann strings and that feathering of the strings.

Yeah, yeah! Still, it’s done in kind of a chamber-y way that has a little bit more of a baroque tone to it than the super Hollywood kind of thing. It’s more like an Eastern European type of tone. Yeah.

I’m curious, Brian, because there are so many moments in this episode, and throughout the series, throughout both seasons that you’ve composed, but in this episode in particular, there were so many moments where we’re getting that one note, that one string note held for so long. I’m curious how that is done, how you know to bring that in. Is that decided when you’re writing it or while you’re actually working with the instrument? That is so effective and it’s like nails on a chalkboard in the same pitch and never deviating.

It almost ends up being something that is hypnotizing. I find that I write most of the music, at least in a sketch way, when I’m watching it for the first time. It’s just kind of in my head. When I see something, I’ll watch it with no music. I’m very much a “first instinct is usually best” kind of person, so I just write down what I’m hearing. That’s part of the mystery of the entire thing. I don’t quite know why I naturally just make these choices as I watch something. I don’t exactly know where that comes from. It is part of the process. I’m such really an impressionistic composer, so much so that before I had the luxury of scoring these beautiful movies and shows and things that people like Taylor Sheridan shoot, in my younger years I would, instead of just writing in a vacuum, I would read a novel and I would write music to it or I’d look at a painting and I’d write music to it. That’s how I learned to compose was not from listening to music. I learned to compose from reading.

You compose through your imagination, from your emotion.

Right. It’s an emotional reaction, so much so that my early years, and we’re talking way, way, way back when I would write music on paper, when I was like 12, I would read these books – I don’t know if I told you this story before – but I was very into both nonfiction and fiction of all sorts, but I loved all the Carl Sagan books and I was very interested in science and astronomy, but I was also interested in science fiction books. I read the Frank Herbert books, the Dune series. One of the earliest things I did that I had down on paper that I really wrote kind of a “score” for, orchestrally, I was like 12 and I wrote to the Dune books. I wrote all these themes. Of course, I imagined in my head what they’d sound like with an orchestra. This was just a dream. It was just a pipe dream. I couldn’t play it on piano because it was too multi-chamberal, there were way too many parts. I don’t have 30 fingers. I can play the melody, but I could never express to my parents or friends what this sounded like in my head. Cut to way, way, way, way, way later, and I’m a film composer and Greg Yaitanes calls me up and says, “Hey, Disney is doing this mini-series movie, kind of a six-hour event of the Children of Dune and Dune Messiah combined as a movie. I’m directing it. Would you be interested?” I’m thinking, “What? Yeah!” What happened was, since I had written this theme, even at 12, by just the nature of that story affecting me that way, there was no way I could even get around the fact that that existed. The theme that’s at the beginning, the very first thing on the soundtrack of Children of Dune and the very first theme you hear in the movie is the theme that I wrote when I was 12. It still stuck with me all those years, that melody. I got to conduct it and have the orchestra play it. Boom, finally the dream of this child reading his science fiction novels ended up being the theme of the movie.

Oh my God! Brian, that’s amazing!

This is literally one of those things that was the dream. Also, this is kind of poetic that as a child I dreamed about this, and then I ended up being able to do it. Sure enough, there it is. Finally, I got to say to all the people who I had described this to, my parents and friends, “Well, here it is.” Now I do that one in concert. When I do my concerts, I always make sure I do that one.

You’re making my heart smile.

Good.

Well, you also made my heart smile at the end of Sins of the Father because after Tate gets rescued, all of a sudden there’s no dialogue at all. It’s just music and somebody picking a guitar, very easygoing as if it’s waiting. But it’s a good wait. An easygoing wait. There’s no dialogue. We just see John getting the call, going into tell Beth and Monica, and then we cut to Rip and Beth outside, and as John finally then comes out and is on the porch crying, it’s just a very easy guitar that then dissolves into Ryan’s [Bingham] song, The Weary Kind. You leave us on such an upbeat hopeful note because as we see John crying, part of it is out of sorrow because the world is changing and he might lose Yellowstone, but it’s also relief.

Yes, it is. There is the other side of catharsis where that coda occurs. Often in these situations, it’s kind of rearranging the natural progression of a tragedy into having the coda not end in a way that’s expected. That’s what’s unexpected about this show that is dark, and that it does these things that you really, I think, are feeling throughout the season, that is going a certain way. Then to have that kind of breath of fresh air is how John Dutton is having his release. I think that with something that has simplicity to it, it allows room for you to have that emotion. If it was way over the top and this big kind of moment, it would end up feeling like different things, like Gone With the Wind or something.

We don’t need Max Steiner here.

Right. No, it’s not that kind of thing. It’s honest. The realism of this is what makes everything feel really contemplated and hits you emotionally right in the heart. Sometimes the restraint is best. there’s a lot of restraint in the score overall. The scenes you’ve even described earlier today, but certainly that’s one of them that we could have gone another way and probably most likely most cases would have gone another way. I think just the instincts that Taylor and I have are so similar that we’re not fighting over these things and we can actually go with the, “You know what I was thinking here, why don’t we do this? I know that’s not …” Absolutely. We don’t have to kind of wrestle over doing something that might be counterintuitive, which is great.

What I love about Episode Ten is that I go back and I look at some of the earlier episodes in the season. For example, you’ve got The Protector, you’ve got Hell to Pay. Your motifs are all there. Especially Hell to Pay. I love that. Where you’re building to the crescendo, then the decrescendo, but you’ve got a twang of strings in there so it sounds like a wolf howling in the distance. You build up you. You increase the tempo. We’ve got tribal drums continually going. It’s either a war dance or pulsing heartbeat. You’ve got little marimbas shaking. You hear something like that, you hear something like The Protector segment where it sounds like you’ve actually got a flute going on in there, but everything is such an Old West feel.

Oh man! Yeah! All sorts of tension. Dissonance and an alto flute, I believe.

You created this entire world of the American Old West and you did this with Season One. Last year we talked about the train sounds and all of that that you incorporated into the music. You continually do that. People could just listen to the soundtracks for Season One and Season Two and they would know exactly what the Old West in the American West was.

Right. Yeah. No, you’re right. Thank you. It paints a very vivid visual picture. Just knowing the setting and then the tone of it, it’s like anything that when I would listen to music that would kind of create a story in my mind. I feel that the kinship and the close-knittedness of the music to this particular story and these visuals is so tight that they evoke each other in a way. Sometimes something can create a picture in your mind, and especially when it can create the exact emotion that you’re going for is what I hope for. If you’re going to have me on music or Taylor directing, the one thing you’re not going to have is kind of just sonic wallpaper for score. If it’s there, it’s going to be there for a reason. If there’s something that isn’t going to say something, if there’s going to be a scene where you have music and it’s not really going to say something, then just don’t have any music there. Sometimes directors will get nervous and they’ll put music everywhere, even where it’s not needed, and then you have no dynamic range for when it comes in or when it leaves. There’s no reason to have music that hides in the background like just some wallpaper. It’s very deliberate. The ratio of efficacy that the music has is very high in YELLOWSTONE because it’s spotted in a way that it is so deliberate that it has to say a certain something if there is music. Taylor and I are very similar in that way; that we believe in that mantra. When it comes in, you kind of key in and you emotionally get on what’s happening. The music does two things, I think, in this as well. The number one job of the music is to create the emotion, but the number two job is also to shape the narrative of what’s happening in the scene which is very much in YELLOWSTONE. As Taylor and I started working together, he realized he could sometimes have in these scenes less dialogue and less kind of exposition than would normally be in it because he felt that the music was doing so much to kind of almost create a musical exposition of literally the story, of who and where. You’re used to themes of, okay, here’s Rip and here’s Kayce and it kind of would outline what’s happening. You didn’t need to have that much dialogue. Maybe it’s more effective to just have the music. It’s interesting how the music has actually affected the way it’s edited, as well.

I know that you have to go, but I have to ask about Season Three.

I’m on season three. I’m doing it now. It’s amazing! It’s amazing! You won’t believe where the show is going but it’s amazing.

You did this to me last year when we talked about Season One and you teased me about Season Two that “you won’t believe where this is going” and boy were you right. Ben Richardson did that to me, too. Of course, Ben didn’t come back for Season Two because of working on Taylor’s next feature.

I’m not going anywhere. I’m doing the score with Breton Vivian who is one of my instrumentalists on Seasons One and Two. He played some of the instruments on it. He’s actually worked with me for, I don’t know, three, four years. This cool thing about the music is that some of it with those mandolins and everything, it’s really fun for me, kind of like a band where you get to play off each other. I’ll play the cello. We’re going to do the soundtrack and everything.

So far this season is intense! And you build that intensity making use of crescendo.

Yeah. It really is. It’s going to build and build. I started working on three, just the music for it, last year. I build up because when we do is I record, thank goodness, I record a lot of things from script ahead of time with orchestra and then do these building blocks that then can be the thematic building blocks for things that I record on my own here by design. I had no idea COVID was coming. In a weird way, it was like, whoa, just a really good kind of coincidence in a way that I was able to do that and now we’re in the refining process. We have these huge building blocks of all the chamber and orchestral music, then on top of it recording all the mandolins and charangos and bouzoukis. I have a balalaika that I’m playing quite a bit on it. There’s all sorts of different ones that you’ll hear that are new stringed instruments popping into the score.

I’m already in love with the Season Three score. The July 5 episode was intense musically, story-wise, too, but musically it was one of the most intense episodes that we’ve had.

It really was. It even gets more so. It’s really an amazing season. I feel like a lot of shows really hit their stride in season three. It’s like the Riker gets his beard in Season Three of The Next Generation kind of thing. Boom! All of a sudden. You kind of have to build characters. The first two seasons, you have to establish them, but then the interesting part is when you break the rules with those characters. What you know of them, now you can kind of do things with them that’s unexpected, but you can’t do that right away because then you would just ruin the baseline for that character. You’d get confused. Now we’re in that zone where you really have the latitude to do really interesting things in the story. Taylor has that long view where he knew where it was going even way back.

by debbie elias, exclusive interview 07/06/2020