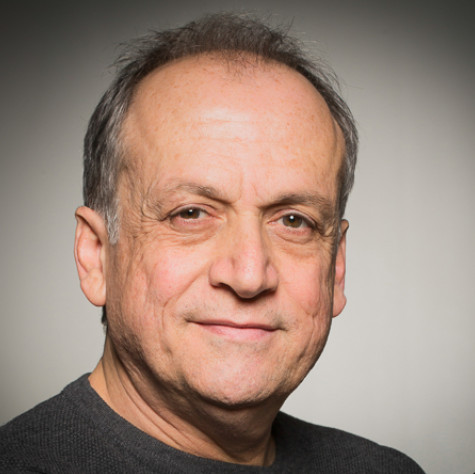

JOE LETTERI is a legend in the visual effects world. A five-time Academy Award winner, including one for technical achievement, Joe’s acclaimed work is best known to moviegoers and fellow craftsmen alike for films like, “Avatar”, “The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers”, “The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King”, “King Kong”, and, of course, the “Planet of the Apes” trilogy – DAWN, RISE and now WAR FOR THE PLANET OF THE APES.

Senior Visual Effects Supervisor for WETA Digital, one of the world’s premiere visual effects companies, thanks to Joe’s leadership and vision, WETA is synonymous with “creativity and innovation” and has not only created memorable characters and cinematic moments, but has helped shape the VFX industry, and by extension filmmaking, with ever-expanding technological advancements which has pushed the development of large-scale virtual production to unprecedented heights.

A big year for WETA, Joe Letteri and his team of Animation Supervisor Daniel Barrett, Visual Effects Supervisor Dan Lemmon and Special Effects Supervisor Joel Whist, picked up both a BAFTA and an Oscar nomination for Best Visual Effects for their work on WAR FOR THE PLANET OF THE APES. Their WETA colleagues, Digital Visual Effects Supervisor Guy Williams, Overall Visual Effects Supervisor Christopher Townsend, Framestore Visual Effects Supervisor Jonathan Fawkner and Special Effects Supervisor Dan Sudick, were also nominated for their work on “Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2.”

Heading into the final voting weeks for Oscar, film critic debbie elias had a chance to go in-depth with JOE LETTERI and talk about the visual effects process of WAR FOR THE PLANET OF THE APES, including the development of the Manuka renderer, Manuka PhysLight tools, and Totara – the next generation simulation tool for creating environs, as well as the all-important element of emotionality of performace.

First of all, congratulations on another Oscar nomination! I am thrilled to be talking with you, Joe! I spoke with your colleague Dan Lemmon back in October about WAR.

Thank you, thank you very much.

I am excited to speak with you now and cover a lot of the things that Dan and I didn’t talk about. One of the standout things of WAR that I hope all the Academy voters really take a good hard look at is that with WAR FOR THE PLANET OF THE APES, you have really captured something with the emotionality of the characters and conveying that through performance, especially Andy Serkis because we have a whole shift in that Caesar, in this film, realizes he’s not a human as he’s tried to think of himself as in the prior films. He now realizes he is an ape stuck in a human world and you really celebrate and capture that and bring it to life with the work that WETA does. Body movement and performance can only go so far, but then you’ve got to tweak the weightiness, the actual physical onus and burden that we see unfold, and what you’ve done in achieving that is just amazing.

Oh, thank you! Thank you! Yeah, you’re right. This film is kind of a turning point for Caesar. It is darker because of that realization and it’s told in almost like an interior monologue in a lot of it; it’s what’s happening behind his eyes. Matt Reeves just holds on these long close-ups of Caesar and it all just unfolds very subtlely and we did spend a lot of time trying to translate what we’re seeing and watching Andy do, to make sure that when you saw Caesar do it, it has the same weightiness and it has the same feel that drew you in to what he was thinking.

It really, it really does. I know that had to be such a challenge and at the same time, so gratifying when you achieved it in putting that together because we’re shooting on 65mm film, which gives you a shallow depth of field in terms of separating your foreground, your background. But then you’ve got to come in and work your magic in painting out, applying, moving those things around and capturing the physical lighting in the computer world.

Mm-hmm. We’ve been really lucky to have three films to kind of work this out on because we started on the first film just trying to model realistic looking chimps, and Caesar was based on something that’s pretty close to a real chimp. We made a couple of allowances in his muzzle design knowing that he was going to have a little bit of dialogue, but we’ve tweaked that over the course of the two films because Caesar has had more and more dialogue, and more and more close-ups. So, by this time around, even though he looks the same, for us, the Caesar that we worked with is a new model. He’s just got a lot more detail in the skin, in the fur, in the eyes especially, and around the eyes, and the way those micro-movements can translate. You see that all reflective live as he’s performing it. So that’s really where we spent our effort, is to just try to lock down on the details on this one.

Since you came on board and you guys knew you’d have three films, giving R&D a great chance to work on things and develop over the course of the years, how exciting was it for you and how did it enhance your own capabilities with the software, the Manuka software, the light tool set?

We didn’t know that we were going to have three films. When we did the first one, we were just hoping it would work, and fortunately, it did, enough to get us a second and a third film going out of the story. But the software that we developed to do this, software like Manuka, that was years in the making. In visual effects, we start to see what we’re going to be called on to do, and it’s a really broad spectrum of work. So we start developing these big tools like Manuka that can handle rendering in a more physically correct way. You try to find the right project to roll that out on to make sure that it’s all ready to go. On DAWN, we were able to use it for some of the background characters, it was the first time we could test it. But on this film, we deployed it in the full close-ups, and that really allowed us to get the richness of lighting that you couldn’t get any other way.

We came up with this idea called “spectral rendering.” Well, not that we came up with it. We came up with the idea that we were going to make it work this time. Typically, a camera records red, green and blue, but you record that after the world has done all its interactions with light. But out there in the world, it’s an infinite number of light colors, and when you have things as complex as eyes or fur and all the light is bouncing around and transmitting, there’s a richness to the color that you can only capture if you can capture the full range of light that’s out in the world. So we wrote this new software on top of Manuka called PhysLight that does that and allows us to capture the full range of dynamic lighting and match it to what the ALEXA 65 was recording, so the two fit together in a way that hopefully defines digital cinematography better than we’ve been able to do it in the past.

I have to tell you, I was so impressed watching this because in the past, in so many films, not ones that WETA has worked on, but where other VFX has been involved, you can often see the differential between what is live and what is computer generated when you start looking at the minutia of the lighting, the cinematographic lighting design. Here, it is impossible to tell. I have watched this film several times. I have had my face right up to the screen in my house looking at it. It is seamless. You cannot differentiate between where the natural production light is and where the VFX light came in.

Well, thank you, Debbie! That’s what we were after. That really was the goal of all this work, to get the technology working to the point where we could just be thinking creatively about the lighting, and kind of fitting what we were doing into the natural lighting that Michael Seresin was doing.

And Michael’s lighting is absolutely gorgeous. And here again you have now expanded the environs that you’re now working in. You’re out there, you’re out in nature, you’re out there with snow, you’re now utilizing a lot of rain. Dan and I talked about that and how it came into play with the fur, which is the best I have ever seen. But then now you’ve got this new cutting-edge Totara . This is going to be the next big thing in VFX, is it not?

Well, it’s one more piece, or one more tool, that we can use because it worked really well for us here. It’s just going to depend on what the next story is, whether we’re going to have to create things like that or not. As I was saying before, we developed a large suite of tools because you never know what you’re going to be asked to do. But then we focus in on the development on what any particular film requires and what the story requires. But there are some things that are universal, and lighting and cinematography are universal for any film where you have to create realism. So that’s why we put extra focus into those tools.

I do have to say it works beautifully, but with the Totara program, I love this. This whole idea of building the forest and natural environs. I find that fascinating.

Again, it just goes back to when you’re shooting out in the real world, what are you getting? We get a lot of stuff for free because it just happens. You know, plants grow and they do what they do, and you go out with your camera and you find a nice spot where the light is coming in, and the composition is what you want, and you just start photographing it. You didn’t have to grow those trees. But if we’re doing it, similar to how you might be creating it on the set, what you would do is carve and mold a bunch of trees and dress them and move them around and hang up a bunch of blue screens and try to make it look as natural as possible just going by eye. And that works, that’s definitely been done in the past, usually on live action, and it can work well.

But I was really interested in the richness that you get in the real world that’s just difficult to create by hand, and that richness really comes from natural growth processes. Things grow and die each year in a forest, and it’s not just the trees, it’s the branches within the trees, it’s the leaves. Everything about it has its own cycle, and if you could capture that variety, I was hoping that you would get something that looks natural. So that’s what Totara did for us. We were able to grow a pine forest on a mountain, let it grow for a hundred years, get that natural kind of feeling where every tree is unique, and looking the way it would based on where it is on the slope of the mountain in relation to its neighbors, and how much sunlight it’s getting, and all these other factors that affect it. Then adding the snow on to it so that you have the weight of the snow on the limbs. Again, all this works in a very natural way if you can kind of understand what the real world is doing and figure out a way to recreate it. So, for us, that was the great thing about Totara, just trying make that all come together for the first time.

And the result is exquisite. Just going in cold and seeing the film, I had no idea you were not shooting on location, on the side of a mountain, that every tree I was seeing was not real. This would be like going up and down a mountainside in the middle of winter in Canada, in Europe, in the Pacific Northwest. The realism is unparalleled.

Oh, thank you. All these tools work together because if you build a forest like that, to render it, to basically image it photographically, is hugely complex. But again, because we were building Manuka in parallel to handle that kind of lighting complexity and those very large scenes, we were actually able to render what we were creating. Because again, in the past, that would’ve been so much data and so much lighting to compute that it wouldn’t have been impossible. But now, you’re getting every interaction as you should in the real world. You know, light passing through the pine needles and bouncing off the snow and doing all those things that it should do.

I’m glad you mentioned light bouncing off the snow because I have to say, the reflection and refraction of firelight and exterior with snow is incredible.

Thank you. That’s one of the things that this whole spectral rendering idea gives us because one of the things we’ve always struggled with in the past is firelight. Because firelight, when you photograph it, it’s pretty much red-orange, but real fire, if you look at its spectrum, has a complete range of colors. That’s where when you see the effect of real fire on skin, on fur, there’s a richness there that’s hard to get if you’re just using a simple color scheme. But because we actually simulate the fire now as a blackbody source and compute the spectral emission along with it, we can photograph that using the same sensitivities that the ALEXA 65 has. So you get that natural feel of fire reflecting everywhere that, again, would be difficult to do, pretty much impossible to do, if you weren’t thinking about all these factors going into it.

And as you mentioned, with the full spectrum of colors with the fire, we see that play out because as you said, when you look at a fire, you see ranges that go into the blues and even some purples, depending on the radiant heat that’s being emitted.

Yes, exactly.

We see all of that and that, of course, then creates a different reflection on skin surfaces, which with apes is different than human skin.

Exactly, exactly. It gives it a real richness really all throughout. Like fur, because fur is just like tubes that are almost like glass. They just refract color through them, and it’s a very deep color, especially with the dark fur but it’s still colored nonetheless, and it changes every time you pass from one fur to the other. That’s the kind of complexity that we wanted to see in this film that we couldn’t achieve before.

Because you’ve been on this ride, the APES ride for all three films now, I’m curious about your research process. Because in capturing the apes, the various kinds of apes, in fact, in each film you’ve introduced new kinds of apes, what kind of research did you and your team have to do in order to realize what we see on screen?

Well, it’s a number of factors. For the apes themselves, you’re looking first off at the model, the general shape. What makes an orangutan look like an orangutan versus a chimp? What are the factors that go into how you see it move? And that would be, what does the skeleton look like because we have to build the skeleton for each of our creatures. We try to then infer what the muscles would be, so there’s a muscle system underneath each one. There’s a fat layer, and how does that affect what you see moving, how does that affect the skin? Especially for an orangutan. The males get those flanges on their heads and they’ve got that wattle on their chest. So we try to break out all the physical components, as well as all the visual components of lighting, and what the skin looks like, and what the fur looks like and how it all interacts.

We have to figure out how to dress all the fur, which is all done essentially by hand, even though it’s in the computer. It’s all hand-placed and hand-groomed. Then we have to work out a full dynamics simulation on top of that, which means when the character moves, what is happening to the fat and the muscles and the fur on top of it. So it’s layers of complexity that, as I was saying before, in the real world, you get all this for free. We have to think all that through to make sure that it all works together and comes together at the same time.

How does shooting with the 65, how does that impact your work? Is it a help, is it a hindrance? Other than the shallow depth of field, which has its benefits and its disadvantages, how did shooting in 65 impact your work?

Well, for us, it’s a stylistic choice. The technical consideration really is the depth of field because shallow depth of field means you have less accurate information sometimes in your background photography. One of the important things that we have to do is look at a background plate and make sure that everything locks down. For example, if you’re in a closeup and you’ve got out of focus ground in the background, but we have to put chimps in the background that have to lock to the ground. If the ground is sharp, you know that you’ve got the footfalls exactly in the right place. If it’s soft, it’s harder to know exactly where it is. So it’s just one of those things that adds a little bit of a technical challenge to it, which we work around by putting other cameras around the set so we can see what’s really going on.

So technically, it adds a little bit of complexity but not hugely. It’s mostly important as a stylistic choice. Matt Reeves wanted that feel for this film, you know the big, wide, cinematic look for it. So we’re happy to go down that route.

What happens when someone like Matt Reeves comes to you with what he wants. Do you have moments of head scratching where he says “Okay, I want to shoot 65, I want it widescreen, I want it cinematic.” Is there a moment where you guys sit there, scratch your head and say, “Hmm, got to think about this” Or is it something you just jump right in and say,”Yes, we’re up to it.”

You know, it’s a little bit of both. We definitely wanted to do it because when Matt first brought it up, he didn’t even have to say any more than that. We kind of knew what he was after and why he wanted to do it, and we thought it would be a great idea. But yeah, you do start doing your homework because you want to make sure that you don’t forget anything that may come up because you’re working with a new camera that you’re not prepared for on the day. So it’s both.

How much liaising is there between you, your team and cinematographer Michael Seresin, in terms of the lighting?

Well, there’s a fair amount because on set we’re trying to capture what Michael is doing all the time. So it’s not so much about direction. For the live action, Michael will set the direction, but because we’ve worked out this way of bringing the actors into the set and capturing them live, that actually is one of our greatest contributions to the lighting because Michael can light Andy Serkis or Steve Zahn, and that’s the lighting that we’ll start with to light Caesar or Bad Ape. I say “start with” because we want to capture the feel of what he’s doing as exactly as possible, but there will be differences because of the body proportions. Apes have deeper eye sockets, for example, so Michael may have a catch light in Andy’s eye, but when we put it on Caesar, his head is in a slightly different position because of the length of his back compared to his legs. That may mean that we have to angle his head slightly to get the gaze in the same place, but now the light that Michael had no longer works.

So we have to kind of make slight adjustments to get the same feel because you want, say, that sparkle in the eye, and we do it in a way that we hope you don’t notice the slight differences, the slight variances that we’re adding to it, that it fits in with the overall scheme. Then we carry that on if there’s a sequence that is entirely digital. We’re looking at that same style so that it doesn’t break with the style of the film, but those will all get lit by us at WETA, and we just pick it up and run with it.

How many scenes in the film were totally digital?

In the hidden fortress, a lot of that was pretty much digital once you were behind the waterfall, except for a small portion that was built for interaction with the humans, you know, when the colonel comes in, the soldiers come in with their weapons. A small piece of that was built and then we used that as a guide and built all the rest of it digitally for the apes. So the general rule is we like to work physically as much as possible but if there’s not going to be live action actors in the set where the photography is really the thing that’s driving it, then it will tend to get built as a digital set.

Does it present any kind of added challenge to you when you have scenes with apes and humans together? When you are making those adjustments, as you mentioned, the light to get the sparkle in Andy’s eye that was picked up. Does that present any kind of challenge to you or anything that you have to consider when we have a tight shot?

In some ways, that’s actually the bulk of our work. Translating what we photographed into what we can create with the apes to get the same feel, and it starts right with the performance. You’ve got an actor who’s a human who may have arm extensions, say for example, to mimic the longer arms on the legs. But they still, even with that, don’t have the same proportion of long arms and short legs that a chimp has. So we might capture that but we’ll have to then look at adjusting that onto our chimp bodies, and that’s going to change the body language slightly, which means the head position and the eye position change a little bit. We have to move all that around so that it still believably matches into the performance of what we got from the actors, and from there, make any lighting adjustments.

Also, looking at facial expressions and dialogue because we think of chimps as very much like humans. They’re closely related to us. They have eyes and nose and a mouth that we can relate to, but they have a lot of features that are different than ours. So when you’re translating an actor’s performance, some of the landmarks that we’re used to seeing in the actor’s face, chimps just don’t have and we have to come up ways to convey a quizzical expression or a smile because these are things that chimps can’t do in the same way that we do.

I’m curious, Joe. If you have Woody Harrelson and Andy in a scene together, Woody Harrelson’s character of the Colonel and Caesar, because you’re working with a real person say on the right and the chimp on the left, is that an added difficulty factor to you because the lighting in the chimp has to match what we have with the human that he’s talking to?

Yes, it most definitely is. But again, that’s the whole beauty of this technique. That’s what allows us to do this kind of integration because we’ll have Woody’s lighting or his presence I should say, affecting Andy’s lighting and vice versa, and we can use that to our advantage. If we shadow or default on Andy, then we animate Woody in the computer so that when we light Caesar, we have a shadow of Woody that falls on Caesar in exactly the same place. Those are things that we just have to look at visually and just to make sure that we have all that interaction working. That’s really all done by hand.

If you had to pick one, do you have a favorite scene or sequence in this film of which you are the proudest of the work that WETA has done?

You know, no, not really. It’s pretty consistent all the way across. I was pretty pleased with the way everything worked across the board. It’s hard to pick favorites.

A proud parent there speaking, I can tell! One last question before I let you go, Joe. You have now been at the forefront with WETA working on this wonderful performance capture, motion capture to performance capture. You’ve worked with Jim Cameron, you’re going to do more with Cameron, you’ve worked with Matt Reeves on the APES trilogy, you worked on “Lord of the Rings” with Peter Jackson. Now that you have completed this journey of APES, what did you personally take away from this experience that you will now take forward into your future work, into the “Avatar” sequels with Cameron and beyond?

To me, it’s still learning about performance because no matter how many times you do this, every performance is different, even if you’re doing it with the same actor. We’ve worked with Andy so many times now, but he does things with Caesar in this film, the expressions that he makes and subtleties of emotion, that we’ve not seen him do before. You just realize you can’t be complacent. There’s no point that have you seen it all. I think Andy said it himself because I know he got asked about playing Caesar when he’s already done King Kong, and he said, “Well, no one goes to a human actor and says well you’ve already played a human before, why would you want to do that again?” Every film is different, every scene is different, and just when you think you know what you should be doing, you’ll see something unique like that that really opens your eyes. But that’s what I love about doing these films. That, to me, is why WAR was so great because it was a whole different direction that we weren’t expecting.

This is the height of emotionality and performance that we see from Andy, that we see from Terry [Notary], and the human counterparts on screen. It’s just amazing the way that you really embraced that and allow moviegoers to experience exactly what they’re bringing to the performance.

Well, it’s nice to hear that, Debbie. I’m glad that it worked because that’s really what we were after. When this franchise first came to me, when Fox came to me with the script for one, I just knew that I wanted to make it because I was such a big fan of the original and I knew what kind of a film it could be. I was really glad that it turned into the series of three films as they were because I just enjoy watching them. I think they’re just really good storyline and good films to watch.

by debbie elias, interview 02/10/2018