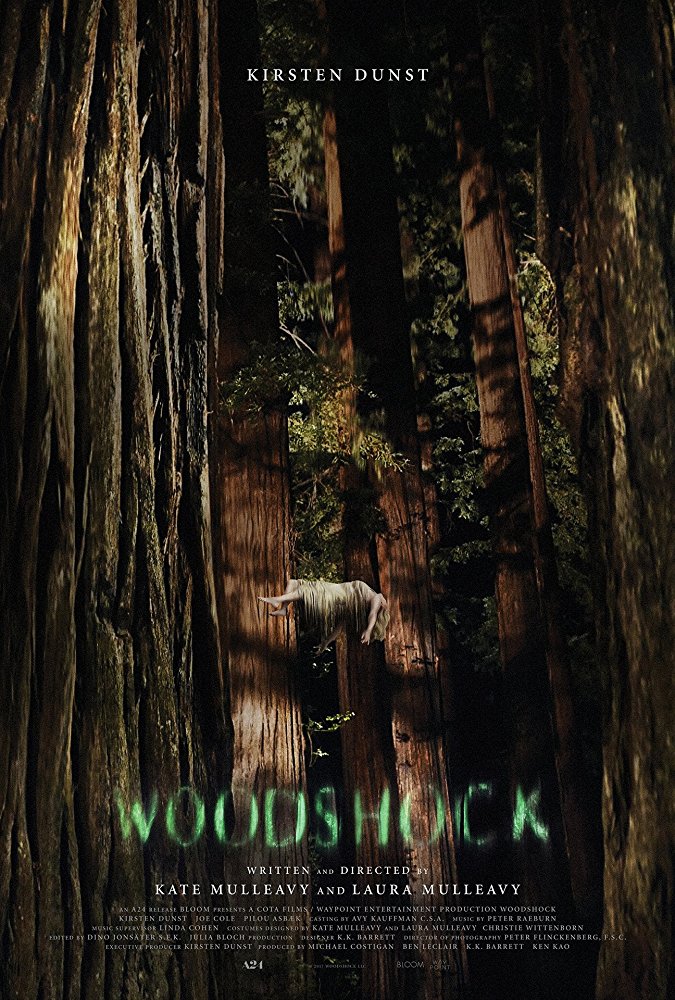

Sensitivity, creativity and passion flow through and from sisters Kate and Laura Mulleavy. Already known for their couture label, Rodarte, they now bring their design sensibilities and visual aesthetic to the big screen as they make their joint debut as co-writers/co-directors with WOODSHOCK.

A visual stunner, WOODSHOCK explores the mind of Theresa, a legal cannabis dealer in redwood country who has a knack for concocting lethally laced marijuana combinations for those in need or, in Theresa’s case, just strong enough to propel her own spiraling psychotropic trauma following the death of her mother. Thanks to an almost mystical yet celebratory visual construct, Peter Flinckenberg’s cinematography is beauteous with its use of lens flares, play of lighting, watercolor effects, layers upon layers of superimposition, unusual and asymmetrical framing amongst the beauty of nature’s redwoods, all to great metaphoric effect splintering reality from altered reality and hallucination. There are an agelessness and timelessness with an added ethereal quality to the overall tonal bandwidth that is beguiling. Kirsten Dunst fascinates with her tortured performance as Theresa while Pilou Asbaek, as Theresa’s employer/friend Keith, deals with his own alcohol and marijuana-infused reality, lending to a wonderfully enticing, yet volatile chemistry, between the two.

I sat down with the stylish and creative duo, appropriately clad in matching Rodarte-designed silk blouses in opposing colors of black and white, for this enlightening and engaging interview into the world of WOODSHOCK.

WOODSHOCK is beautiful. A visually exquisite film. As I was watching, I kept getting the sense of a Terrence Malick kind of feel.

KM: Oh thank you. I’m so excited to hear you say that. Because I come from a world that loves visual, and with filmmaking especially, I think those are films that I connect to in an extreme way. The way that we developed the visual aesthetic of the film and the world of it was because we were gonna go on this stream of consciousness, kind of subjective journey, with this lead character Theresa. We felt like the entire world of the film had to be inside of her head. And because of that we had a very specific way with the production design and the way you experienced her inner world. Interestingly enough we didn’t have a lot of film references, although Laura and I love film and we love so many different directors, so many different movies. Even in our editing room we had a poster of The Ecstasy of Saint Theresa. So it was kind of an interesting thing. But I think that came more from our own creative process, in terms of what we felt like when we would work on shows. We would always get inspiration and just work in our own headspace. I think when we wanted to film it felt more creative to work with a cinematographer. We would say every day on the set, “How can we shoot this in a more interesting way?”, instead of burdening him by saying “Here are all the shots we want to reference.” So, I think that led to a real creative freedom.

LM: And I think too, Terrence Malick is a great example of stream of consciousness narrative in filmmaking and about the slowness of nature. Someone said to me, “You know, it’s so interesting that we slowed down time.” So you’re at that pace. Theresa’s lost time in this kind of moment of isolation of grief. She’s kind of stuck in a world where there isn’t time. It’s very abstracted for her because I think it’s meant to feel like your world’s changing. The things that you would normally say or do; you would wake up and you know when you are awake, and when you go to bed, but she’s sleeping all the time. There’s things like that. But, I think when I probably first loved his films, or discovered them, that was the thing that struck me about them. And as a reader, and someone that was an English literature major, the idea of a stream of consciousness narrative always seemed the most thrilling to me. It just seemed I could relate so much to it and this idea of getting lost in someone’s head, or the way they are talking about things.

KM: And I think this is a movie about the mystery of the human mind and life. The truth is, which you know, we were saying [to] come inside this woman’s mind as she’s expanding and opening different doors that lead to different doors opening and maybe parts of the consciousness that we don’t always access. In that sense, there is a real parallel to nature. Like Laura said, it’s like almost slowing down to the pace of nature, and at times speeding up.

And then there’s your metaphor. The fact that you set WOODSHOCK in redwood country, because you’ve got the deforestation issue, equates to Theresa’s world collapsing around her. But at the same time, there is the agelessness and timelessness of life and nature.

KM: Right.

LM: You’re making me cry. It’s true. That’s a beautiful way of saying it. That’s the story.

This is the gift of good filmmaking. This is storytelling and you’re using all of the tools. Then you take all of that visually, and what you have done collaborating with your cinematographer Peter Flinckenberg, is just magical.

KM: I feel like we were as children. We grew up right in Santa Cruz. Our father was a mycologist, so he studied mushrooms, so we were around a lot of people that were in nature. And we were always in the redwood forest. That landscape had such a connectivity, and not only in our creative process, but also, I think in our sensitivity to human experience. I think Laura and I realized standing in those trees, how small you are in the grand scheme of life. When we started working on this film, the starting point was Laura and I both saying, “Well we want to do something where we really explore what these trees make you feel like” because, I think it is vitally important for us to connect to these types experiences because we’re moving away as human beings, further and further from, from nature and the fact that we’re a part of that. I think that that’s where this all started. Theresa was born from that landscape and I think her journey is very much linked to the beauty, but also to the destruction. One of the things we would say is, “Well, imagine if you lived, if you grew up in this area, and they were taking down trees that were larger than the Statue of Liberty.” They’ll tell you that when a tree would come down like that you’d feel vibrations for miles. We would say, “Well, what’s the psychic repurcussions of that?” Because you put up defense mechanisms and then you don’t really experience, you try to distance yourself from the experience. So we said, “Well what if you’re really sensitive and that’s just something that your body absorbs?” So I think she was born from those questions.

LM: I sometimes look at it as a creation myth. This character – there’s this moment that she is standing in this riverbed. It’s very beautiful and vast. It’s like the Venus de Milo. She comes out of this oyster shell, or the clam shell, but she’s out at this river bank. And it has so much power to me, the more and more I see it, I think about that more and more. And I guess it’s because she is so connected to these two sides, the human imprint and then also the impact of nature and the beauty of it. [But] she’s never connected to humanity. She can’t connect to the people in her life. I would say that at the end when she finds that tree and she dissolves into it, that’s such a powerful feeling for me because she’s gotten to a place where she’s been so disconnected, that this is the thing that she’s longed for. She’s one with it and she’s a part of it, and she’s transformed. So the levitation is very much cathartic. You know, you go through this emotional journey with the character and instead of feeling weighted down by this, the heaviness of the story, I feel like it’s enlightening in some way. I don’t feel burdened by her story. I feel this is an exploration that I can connect to and that I can relate to myself.

KM: For me, I watch it now and I think Kirsten’s is such a nuanced performance in this movie. She’s so amazing. We essentially asked her, we need to take all your internal fears, we need to take the sensitivity that we have with this natural world, and we have to bring it external. It’s not going to be a backstory that explains things to people. You’re never going to get to know Theresa necessarily through the characters around her. In a sense you do, but she’s so disconnected with them. I would say Keith is different because he knows something about her. But even in her own home, the man that she lives with is a stranger. A stranger to her and, he’s a stranger to the audience. So we asked her to bring so much internal processing, external. I can’t think of anyone else that we could have done that with.

LM: Who could touch a wood wall and make it feel like everything you needed to feel? It’s like if she’s rubbing a real tree, she’s talking to her mother. That imprint? That’s a very beautiful thing that she’s somehow able to access and convey.

I’m glad you brought in the character of Keith. I was so drawn to Keith, and to Pilou Asbaek’s performance. I really wanted to learn more about Keith.

KM: We kind of did that on purpose.

LM: He’s seductive. That’s the character, he is seductive. He’s the character that has no boundaries, he doesn’t have rules. Even Theresa’s is like, “Why can’t I be like that?” She’s so burdened and holed up and isolated, and she’s like, “How come I am weighted down by this decision that I’ve gone through, even though it’s so giving and beautiful.” Because of her experience at the beginning, she interacts with the world so differently than Keith. And she has a rage towards that. So, he is supposed to be this thing that you care about, but you’re confused by, just because she is.

KM: He also represents some of the freedom that she seeks. In going back to nature, part of what she embraces is the wildness of human nature. Lets not forget, we have clocks, we do a lot of things to make logical, to regulate our lives. I wake up, I eat dinner at night. Why? I don’t know. But I was told from a little kid, we eat dinner at night and breakfast in the morning. We make a system. Theresa eventually abandons the system and in a sense, Keith is on the road to that, but he’s an interesting character because in a lot of ways, a lot of what we did with Pilou and those scenes, was improv-ed. The first days of shooting, he said, “I don’t know how to improv. I won’t be able to do that.” And Laura said, “I need for you to really quickly shoot this card scene, this poker scene.” We go on camera and he improved the whole thing, so Laura said, “Okay great. Every scene we shoot with you as Keith we’ll give you something before we shoot it, and we’ll just change that each scene and we’ll see where you go with it.” So everything, like the birthday candle, I gave him that trick candle right before shooting, that all happened in one take. The toothbrush and the bird, we both gave him the toothbrush right before. But all of that was about that the character is free. So, whatever we captured of him in the film really was not only the freedom of his performance, but I think also just the freedom of what that character was.

Of course, by having Keith, creating him the way you do, it really gave your music supervisor, Linda Cohen, a chance to shine with your needle drops.

LM: We said, “This person would have very specific music tastes.” And source music was only given to him. It wasn’t given to Theresa. Theresa had score. Keith had source music.

KM: It’s interesting how you can use things like that to build understanding in an audience. We always said, “Keith represents Northern California counterculture.” Since we grew up there, there was this push and pull of the character that’s this kind of danger; dangerous, yet seductive. There’s something attractive about this personality. And wild, not burdened by rules, and that’s what counterculture means to us. So that’s kind of where the music needed to slide in. Linda’s amazing. She just got it right away with Keith. Linda was so great. We met the composer that did the score through Linda, too. When she came on board with this movie, she said, and every one felt this way. “You can’t put anything that doesn’t belong”.

LM: No temp music. Nothing to even help the editing process. We had to meet our composer and start working on things with them right away.

KM: Theresa struggled so much to have human connectivity. If you put in a bunch of excess backstory, or dialogue, or music that didn’t belong, then it kicks you out of her mindset. I think one of the most interesting things, no matter how you experience the film, the consistent thing is that you are in her headspace.

LM: It was so sad because when we requested the Suicide Song [“Dream Baby Dream”], the track that’s the last source cue, I remember we said we were looking for a song and we all decided this would be good. And then Alan Vega actually passed away two weeks after we requested it. And I was like, life is so strange. You know? Everyone was so heartbroken. He was such a creative force. So, that even felt powerful. That’s the power of music.

Now that you have made it through your first feature, what have each of you learned about yourself, that you will now take forward into your future project?

LM: I called my friend one day on set, and we were shooting. We were in Keith’s apartment. We did all of Keith’s apartment work together. And I remember we were getting ready for the big scene at the end. I called my friend Autumn, who would visit us, and she’s actually documented us for 12 years. I said, “Autumn, I don’t know what’s wrong with me. I feel things on the set, that I’ve never felt in my entire life. Things that I didn’t even know I was capable of feeling. I don’t even know how to describe what it made me feel.” That was so eye-opening. It made me feel so empowered. I don’t know what it was. It was like a little light bulb went off in my body and told me, “Whatever you do or worry about, you have to just follow your gut.” I always believed that before, but even moreso now. So it’s all about trusting your instincts, and just being really open to the creativity in the moment. Kate and I have always said, in wanting to write your own script, it’s just a freedom it gives you later on because, you really know your subject. We always say, “Well, we wrote the story, so if we’re gonna change it on set, because of something, why not?” It allows you something that is more free. And that, I think, comes across in the type of work that I want to make. I feel like this film should feel like a watercolor. We were really inspired by Gerhard Richter’s paintings, where he smeared out the canvases and images, and things like that have always had power over what we make.

KM: It’s actually funny. When you finish that final sound mix and you’re like, “This is now really going to be done.” But, it’s hard to let go of it. It must be like when a kid goes to college. But what I discovered most, was that for me, it’s about having something that I want to communicate and say and wanting to do it in a way that makes people have to think. And it’s not something that you just say, “Here is the spelled out version of what you walk away with in this film.”, because I’m also interested in what someone else’s human experience, that might be vastly different from the character in this movie, vastly different from perhaps even mine. But they might see it and say, “And this is what I think. And this is how I interacted with it.” And that’s what made me say, “Oh I wanna make more movies.”

LM: I love going to a movie and leaving and talking about it with my friends. It’s not good when we leave and don’t have anything to say. You know what I mean? You’re just like, “Okay see you tomorrow” versus three days later, you’re texting your friend, “What did you think of that?”. It’s such a powerful way of communicating in the world. It’s the modern art form. I always say, things that grow with you and you think about, they just affect you over time.