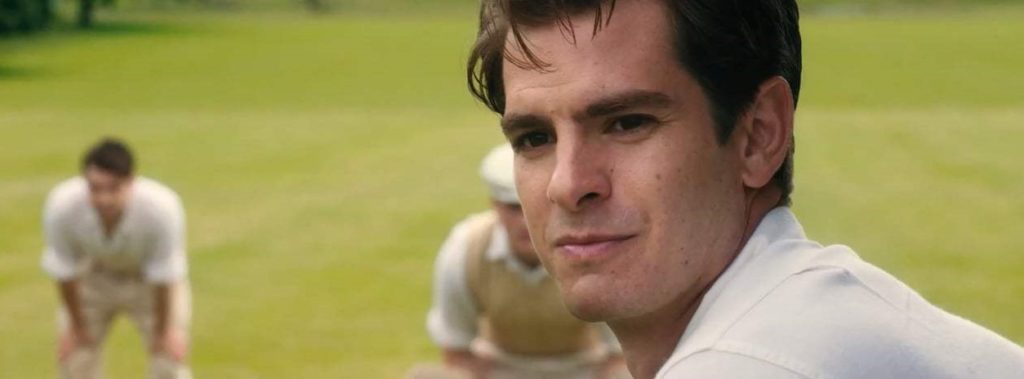

Andy Serkis now proves he is a force to be reckoned with behind the lens as well as in front of it as he makes his feature film directorial debut with BREATHE. A sweetly exquisite film, Serkis captivates with the beauty and emotion of BREATHE. The performances by Claire Foy and Andrew Garfield are indelible while their chemistry is off the charts. Don’t be surprised if you hear one or both of their names come Oscar nominations morning.

Based on the true story of Robin and Diana Cavendish, we first meet the pair in 1958 as they meet for the first time at a late-colonial period garden party complete with tennis, croquet, and politicos in Kenya. Robin, a tea leaf distributor, is immediately smitten with Diana and she with him (although she plays hard to get). On marrying, the couple is in Kenya where Robin is working when what he believes to be the flu turns out to be much worse. He has contracted polio.

Paralyzed from the neck down, the couple is transported back to England where Robin is hospitalized. Under the care of doctors who believe that the couple must accept Robin’s fate as being bedridden, paralyzed, and hospitalized with a respirator for the remainder of his life (which doctors claim will be only three months), Robin becomes suicidal. Undeterred by Robin’s condition or mental state, Diana is determined to have a life as a family which now includes a young son conceived prior to Robin falling ill.

Fighting the hospital administration, doctors, and Robin, Diana restores hope and a willingness to live within Robin, finding a way to bring him home and care for him herself thanks in large part to their friend, Oxford University professor, Teddy Hall. With a mechanical mind and somewhat of a tinkerer and inventor, Teddy and Robin together start conniving and creating inventions and solutions (including a wheelchair with built-in respirator) that allow Robin to sit, have a form of mobility, and even travel to other continents. It is noteworthy to mention that the wheelchair Teddy initially created became not only the first of ten upgrades built for Robin over the years until his death in 1994, but was the prototype for devices of this type the world over.

The story of Robin and Diana Cavendish is itself amazing. And what a love letter by producer Jonathan Cavendish to his parents. Written by Bill Nicholson, the script is almost magical as one can feel the heart and the uplifting emotion of the story within not only the dialogue but the characters. There is an honesty and sincerity that permeates both the script and performances, defying any sense of patronization or cynicism. Capturing the true spirit of the Colonial British “stiff upper lip”, each character is imbued with this trait from beginning to end. Nicholson fills the script with lightness and laughter in the Cavendishes approach to life that is then elegantly transposed visually by Serkis and cinematographer Robert Richardson. A beautifully crafted dichotomy juxtapositioned against a horrible disease. But it’s the performances that bring to life each of these special individuals whom we meet.

Notable is that the script doesn’t weigh us down with the disease and ramifications of it. When viewed in the context of the entire film, Serkis and Nicholson get to the point of the disease and the resulting paralysis and medical dilemma but spend the bulk of the film celebrating life. There is breezy, bright tonal bandwidth that is refreshing. Many directors might have opted to wallow in the “tragedy” of the disease, but not Serkis and Nicholson. A key scene, however, involves a German medical unit where the patients are all in gleaming white, stainless steel, and mirrored iron lungs with only their heads visible, all stacked up like something futuristic and alien, or what might be found in a Jodorowsky film, even lending itself to a sense of being a twisted holdover from the days of Hitler’s Nazi regime. Striking and chilling is the silence in the room after Robin rolls in and then Robin, Diana, and Teddy roll out and there is no sound in the room.

Tom Hollander is nothing short of mind-blowing with a dual performance as Diana’s twin brothers and Cavendish friends, Bloggs and David. You find yourself doing a double take at Hollander’s ability to create and emote two distinctive personalities but with a shared ethic of heart, love, friendship, kindness, is amazing. Be he playing opposite himself in key emotional scenes or engaging with Foy, Garfield and Bonneville, Hollander’s authenticity and sincerity soar. This is the one area where Serkis employs some seamless technological wizardry and does so to great effect.

And speaking of Hugh Bonneville, what a delight! He captured the essence of a professor and scientific dabbler with lovely aplomb and served to add more of the visual levity within certain scenes thanks to his sometimes perceived bumbling and fun-loving professorial joy.

Thoroughly enjoyable is the wide-eyed horrifying amazement of Amit Shah’s Dr. Khan when engaging with Jonathan Hyde’s Dr. Entwistle. And of course, Stephen Mangan’s Dr. Aitken provides not only the forward-thinking medical perceptions of the disabled but thanks to Serkis’ direction we see many scenes where he places himself on an eye-level playing field with Garfield’s Robin. Not looking down or bending over, but actually eye-level. Speaks volumes metaphorically. But never more do we see that metaphoric equality than during a third act chess game where Robin is asking Aitken the ultimate favor. Not only do we face one more move before “checkmate”, but two men going eye-to-eye discussing the one thing we all share – death. In that moment they truly are equals on so many levels. And of course, that’s where we need to break out boxes of tissues.

But it’s Garfield and Foy who command our attention, and our hearts, from start to finish.

The attention to detail both in the script and dialogue and then the visual realizations of that are outstanding. We are welcomed into the emotionally upbeat world of Diana and Robin and thanks to Robert Richardson’s breathtaking camera work (notably the aerials and crane work with sunsets and the widescreen cinemascopic take on the visuals and then the contrasting ECU’s of Garfield’s face) we are emotionally immersed in each moment. The storytelling design of the lensing is a key component to BREATHE as Richardson and Serkis open the film with wide angles, wide vistas, yet keep images of Diana and Robin separate, ultimately joining them into the same frame in Africa where everything takes on even greater scope of life and joy and we feel them become one. But once Robin is struck by polio, images start to split the two as Robin becomes more withdrawn and wishing for death. Framing turns into close-ups and in the case of Robin, ECU’s on the eye, the lips, the trach, the pieces of the respirator. However, as we see Diana’s determination to will Robin to live and the efforts she makes to give him a life that will make him want to live, the camera starts to widen. Frames include Diana and Robin and then widen even further to accommodate the incredible support system of friends who surround them.

Where Andy Serkis surprises is with his tacit acknowledgment of the importance of sound. So many directors often miss the boat with sound but not Serkis. Never do we not hear the breaths of the respirator (but for when the dog pulls the plug or in Africa when the respirator shorts out). It is the heartbeat of the film. In moments when the sound of the respirator stopped, so did my heart and my breathing, believing that would be the moment the joy we were witnessing in the life of the Cavendish family was ending. But then, that was not to be and the minute the sound of the respirator started again, so did my own breathing. Sound is a very powerful tool and hats off to sound editors Ian Wilson and Becki Ponting for their exemplary work.

But hand-in-hand with the ambient sound, the respirator, and the dialogue, is the score. A beautiful melodic score that is light, lilting and fun. We feel happy hearing Nitin Sawhney’s composition even in the darkest moments of disease. There is instrumentation which sounds like some triangle and quirky little musical tones that just keep the mood upbeat and happy, allowing for ( *collective classic film sigh here* ) Bing Crosby and Grace Kelly to get the heart beating faster and the waterworks flowing with “True Love”. To the best of my knowledge, this is the first film to ever use that song outside of its original use in “High Society”. And what a perfect song it is indeed to tell the story of Robin and Diana Cavendish.

It would be remiss not to mention production designer James Merifield. Wonderful job designing not only for different eras, but different countries, different facilities – the 1960 English hospital, the bush hospital, the Cavendish house and how it took on the feeling of a home over the years and as Robin’s investments paid off to give the family some comfort, the futuristic death house German medical facility, party scenes both at the Cavendish house and in Spain, and of course, the upper crust garden party where Robin and Diana first meet. Merifield is a master of minutia and meticulous detail. Just take a look at his work in the over-the-top pink and red almost cartoonish Regency world of “Austenland”, the more downtrodden period piece “Effie Gray”, and of course, “Brighton Rock”. All rely on those little details of design, something which Merifield brings to BREATHE.

There is much tacit commentary in BREATHE about humanity; our approach to life, to each other, to the disabled, to medicine. This film stays with you long after the curtain closes, providing food for thought and for the heart on top of being an award-worthy film.

BREATHE makes you want to do more than just breathe. It makes you want to live.

Directed by Andy Serkis

Written by William Nicholson

Cast: Andrew Garfield, Claire Foy, Tom Hollander, Hugh Bonneville

by debbie elias, review 10/10/2017