By: debbie lynn elias

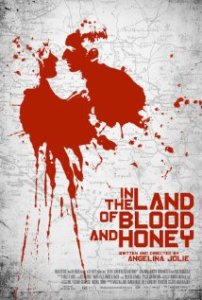

I never thought I would ever be writing these words: I am beyond impressed with Angelina Jolie as a storyteller and director. Marking her debut as writer and director with IN THE LAND OF BLOOD AND HONEY, Jolie takes us behind the lines of the Bosnian war that ravaged Europe in the 1990’s. The bloodiest and deadliest European war since WWII, much of the world turned its back on the savagery and war crimes as it happened. Many of those crimes involved genocide and sexual violence to the women of the region. Set against the backdrop of the war, violent and graphic and made with no apologies, IN THE LAND OF BLOOD AND HONEY, is the story of love, conflict and the emotional, ethical, physical and moral toll it takes not only on individuals, but on people as a whole.

Danijel, a Bosnian Serb officer, and Ajla, a Bosnian Muslim artist, are young and in love. But during a romantic interlude at a café, all of that changes when bombing begins as an ethnic war for territory and power explodes in the region. Ripped apart due to their cultural differences and “duties”, Danijel and Ajla are separated, probably never to be together again. But imagine their surprise when months later they meet again under the most arduous and heinous of conditions.

Danijel is now serving in the Bosnian Serb Army under his father, General Vukojevich. Ajla has been taken prisoner by troops under Danijel’s command. As women are aligned firing squad style, soldiers pick and choose who lives, who dies, who do they sodomize and rape on a table in the freezing cold in front of the other captives. As Ajla is picked for the latter, Danijel spots her, and with love still in his heart, rescues her from this torture, claiming her as his own. But is it really rescue.

Knowing she must publicly “play dumb” in order to remain under Danijel’s protection, you see and feel their once love filled connection, but as time and war move on, the ambiguity of that relationship grows as Danijel becomes lost in being a captor while Ajla just looks to survive in an ever increasing hell.

And while Ajla treads carefully with Danijel, her thoughts are never far from her sister Lejla, whose infant child was murdered, tossed from a balcony, by Danijel’s men, giving rise to the question of blood being thicker than water.

Breaking onto the scene are well known Croatian and Bosnian actors, Zana Marjanovic as Ajla and Daniel Craig look-alike Goran Kostic as Danijel. An intensely personal film to not only Marjanovic and Kostic, but all of the actors, Kostic grew up with a father who was a general in the Serbian Army, something that he tapped into as Danijel. “My father is an army officer in the Serbian army, but that’s where the similarities end. His record is clean and he’s retired. At the same time, coming from Sarajevo in Bosnia and being there for the first 20 years of my life, and having a father that was a very dominant, strong figure in our family, it was easy to tap into that experience from the first 20 years of my life and transfer some of that emotional landscape to my performance of Danijel. My concern was the fact that we get to see him pure and light, and then we see him as something completely different. It was easy to jump from one box to another. What was more difficult was to show the different colors that Danijel goes through, from white to black.” Kostic does an impeccable job of giving Danijel an emotional weakness that prevents him from choosing between love of his father/country and love of Ajla and humanity, giving rise to the greater internal conflict – why are we fighting?

As for Marjanovic, who escaped Sarajevo during the war, “That’s my childhood and that’s what I remember, and that’s the period of my life where everything was perfect and happy and lovely. My parents were happy, and we had a home and friends. . .All of that was taken away from us, in just one night. With the first shotgun, everything changed. I had to grow up fast and realize what was happening. So, that innocence was lost for me. Revisiting it was very difficult, for me, personally.” Most notable about Marjanovic’s performance is her conviction and strength of character, delicately nuanced with emotional vulnerability. On the whole, she has little dialogue but rather, speaks with the most expressive eyes, giving one a sensory feeling of pain, heartache, anguish and yes, even calculated strength.

Vanesa Glodjo, who plays Ajla’s sister Lejla, was herself a teen in Sarajevo during the war and recollected at press day of running between sniper bullets on her way to and from school. Seeing her on screen, she brings a very palpable and real fear to Lejla that grabs you as you watch. So genuine, there are moments one thinks they can feel her terror. Establishing the incredibly powerful sisterly bond, Glodjo and Marjanovic jumped headfirst into their roles. Both only children, they were unaccustomed to sisterly sharing of clothes, boyfriends, and secrets. As Glodjo pointed out to Marjanovic during production, “We don’t have that much time where we represent them as happy sisters, living a normal life. We have to use that time to really feel the bond between the two.” Crucial to the climactic elements of the film, the two women jumped into the touchy feely girlie stuff in order to achieve the necessary relationship.

One of the most pivotal and powerful relationships is that between Danijel and his father. For Kostic, it wasn’t acting between he and Rade Serbedzija. “I knew of Rade for a long time, but we’d never worked together. When we met, it literally took three minutes for me to realize that that guy really is like my dad, and Angelina believed it. In the scene where Danijel gets slapped a few times by his dad, we were not really pretending or acting.”

For those unschooled in the Bosnian War, Jolie uses the character of Nebojsa, Danijel’s father as an educational device. Played by the extremely talented Croatian actor, Rade Serbedzija, Nerbojsa gives a relatively accurate history lesson on the region going back to the days of the Turks in ancient Europe which rather concisely brings us to the point of the war. As Nerbojsa, Serbedzija paints a portrait of old school mind set, narrow-minded in voice but conflicted in his heart, especially when confronted by his son.

Written by Jolie primarily from the point of view of a woman, specifically, Ajla, at its core the story “deals with the sexual violence against women. . .the internal struggles that a woman goes through and a woman’s point of view maybe makes it a little different. But, so much of my focus was also trying to understand the men. I was trying to put myself in the men’s shoes, which was the biggest challenge for me. . .But, at the heart of it is my heart. . .The question of whether or not I could turn against somebody I love and what that would take would be the relationship that I would relate to; but especially the focus on the violence against women and the way the sexuality is handled.” With this mindset, one might think that the story is more “feminine”. Trust me. It’s not. Never have I seen a female writer or director, but for Kathryn Bigelow, so completely capture the testosterone infused elements of situations and characters, that is until now.

Because of the emotional paradox between Ajla and Danijel, while Marjanovic, Kostic and Jolie would rehearse scenes, ” and then we would invite the crew, and they would stand and watch the scene and know how to prepare it, while we just sat and talked about it, during that time” according to Marjanovic, when it came to she and Kostic, “I just had to stay away from him. I’m a rational person, and I’m not a method actor. . .[but] You’re very vulnerable and you’re very fragile.” And given the often violent and volatile nature of the onscreen relationship between the two characters, it was refreshing to learn from Marjanovic what a perfect gentleman she had in Kostic. “Goran is such a gentleman and such a wonderful actor. I remember the first day, we shot one of the most difficult scenes, in the concentration camp when the women were just getting off the bus, and he had to hold me over the table. He was a meter away from me, and we kept repeating the take. I said, ‘Are you going to get closer?,’ and he said, ‘Oh, can I?’. I said, ‘Yes, you needed to.’ He said, ‘I just needed you to tell me that it’s okay.’ He really couldn’t do it, until I said, ‘Go for it!’ That made me feel very comfortable because I knew he’d watch out for me.”

Key to the success of the story structure is Jolie’s collaboration with her cast. Giving them time and space to give their input as to what was being said, she approached the subject matter with “a great tenacity and a great cautiousness” while at the same time, giving all of her actors, survivors of the war, the time and space they needed to bring justice to the characters and story.

Jolie also looked to her actors for guidance in the physical performance. “Because I’m not from the region, in many ways, they directed me. I can’t direct Vanesa [Glodjo] and tell her how to run across sniper alley. She was there, so she can tell me. So often, I was the one asking them, ‘Does this look right? Did we get this right? Does that sound right? Tell me about when your neighbor’s baby died. How did she react? What happened? Can you give me more detail on that?’”

A technical and emotional mine field and finding it impossible to “soften this kind of war”, Jolie’s direction is technically masterful. Calling on cinematographer Dean Semler, the use of fractured light and shadows is a powerful emotional component to the picture. Particularly compelling is the brightness and light of “the white room”, Danijel’s “prison” for Ajla. A critical part of the film, this was particularly challenging for Semler as considerations had to be given to interior light, time of day, camera angles and metaphoric emotional contrast and imagery of a particular scene and sequence in Ajla and Danijel’s relationship.

Adding gravitas and impact is the extensive hand held lensing which, according to Jolie, arose out of economic necessity and to further the story. “Part of [using handheld] was that we had no time. It takes a long time to set up a dolly track. For example, the end scene between Ajla and Danijel was very much aggressively over one shoulder on the other. [Dean Semler] told me something when we first started. He said, ‘You never split your lovers. You never separate them. You always try to keep your lovers connected in a shot.’ . . .We also wanted to make it feel like a big film. . .and we knew that we wanted it to feel real, and reality is not so staged. Many things had to be broken up in this way. You had to be inside with everyone. You had to inside with the women who are the human shields, so that the audience would feel that.” The result is magnificently personal and intimate.

When it comes to discussing their director, Marjanovic and Kostic have nothing but praise for Jolie both in her directorial skills and her humanity. According to Marjanovic, “[Jolie] knows exactly what she’s doing. She gave the victims the strength they actually had, which is why they’re survivors. Bosnians, as people, are not only victims; we’re actually survivors. And, it’s so important to know that. . .she went through this intimate, personal perspective and, through that, she really engaged the audience to watch the film as if it could be them. It’s not some people, somewhere, at the end of Europe, that’s maybe not even Europe, and they’re Muslim. She gave Bosnians dignity, and I really appreciate that. ”

Kostic is equally effusive. “She glides between the problems. She never does it abruptly. I’m sure she’s processing, but when it comes to her expressing herself, she’s always very nice, structured and thoughtful. She truly is a lady, in every meaning of that word. Even when she directs, she does it with such a gentleness, which puts you in a good place, as an actor. That relaxes you. . . With Angelina, the process is truly about incorporation, learning, and giving space and time to one another, the environment that she creates. You forget that she’s there. At the same time, at the end of the day, she would draw the line and say, ‘This is my decision’, and do what she had to do.”

If I didn’t know going into this film that IN THE LAND OF BLOOD AND HONEY marks Jolie’s directorial debut, I would never know, as the level of technical excellence belies that of a typical first-time director. Making this an even greater cinematic achievement, Jolie shot two films in the space of one. One in English and one in Bosnian. Shooting it scene by scene, first in one language and then the next, Jolie “[W]rote it in English because I had to. And then, when we had it translated, we had it translated by different people from different sides, to make sure the translation was fair and balanced. . .We felt that the reason for making this film wasn’t just for the people of the area, and we wanted it to be authentic. And yet, we know that there are a lot of people out there that we want to learn about this part of history and speak about these themes, but those people often don’t go to foreign films. So, we said, ‘Could we do this?’” Thanks to Jolie’s professionalism, preparation and expeditious filming style (within the first week of shooting the two versions, Jolie was already ahead of schedule and had saved an entire day), it quickly became clear that they could shoot two complete versions. And all of the actors agree that by shooting in their native language, it helped their performances, giving them “the root of the language and the dynamic and the gestures.”

A 41 day shoot with a $12 million budget, Jolie “had three and a half years of war and many different seasons to re-create. I found out how much snow cost. I’d say, ‘I want to snow this whole area of Yugoslavia,’ and they would say, ‘Okay, well that’s $100,000 worth of snow.’ I would say, ‘Okay, so what’s $20,00 worth of snow?’” And shooting in two languages, everything was already doubled. “Suddenly, the already tight schedule was tighter. We had to select scenes that had to go. We had to cut the script as we went, and we had to condense things.” With a first cut at 4 hours and 20 minutes, given the completeness of the final product makes Jolie’s scripting decisions and Patricia Rommel’s editing beyond amazingly concise.

Admitting her love for “being on the other side of the camera, . . .with the crew, on the outside. . .in the dirt, working through all the issues”, I personally can’t wait to see what the future holds for Jolie. With a clear, compassionate and concise voice, I welcome her newfound talent with open arms.

Given her world travels, awareness and humanitarian involvement the world over, I asked Jolie, “Why Bosnia” as a backdrop for this story. “We wanted to make a film that’s universal and that could be anywhere, but I landed on Bosnia because I remembered it. It was my generation. I was 17. I remember where I was in the ‘90s, and I felt a guilt and responsibility for not knowing enough and not doing enough.”

For Kostic, “It was important that it was a female voice and a female director, as opposed to a male director.” Personally, I can think of no better voice than that of Angelina Jolie to tell this story. With IN THE LAND OF BLOOD AND HONEY she has taken a giant step forward in “doing enough.”

Zana Marjanovic – Ajla

Goran Kostic – Danijel

Reda Serbedzija- General Nebojsa Vukojevich

Vanessa Glodjo – Lejla

Written and Directed by Angelina Jolie.