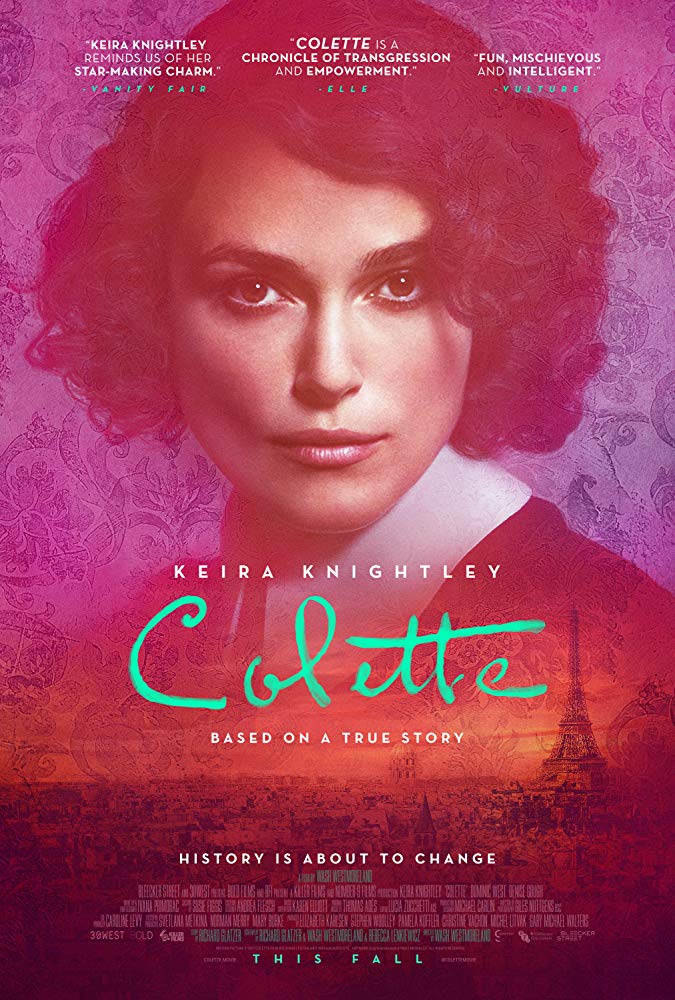

Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette aka Colette was more than the French novelist whose works have been read by so many of us. She was the toast of Paris and undoubtedly its most famous female author. In 1948, she was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature. In 1944, she published her most famous work, “Gigi”, which went on to be adapted for the 1958 Academy Award-winning movie and eventually the 1973 Tony Award-winning Broadway production. She was also an actress, a journalist and most notably, a feminist striking blows for equality for women in the early 1900’s. But just who was Colette? That is the very question that writer/director Wash Westmoreland and co-writers Richard Glatzer and Rebecca Lenkiewicz answer with this latest film, COLETTE, with Keira Knightley starring in the title role.

Focusing on the period of Colette’s meeting and marriage to author and publisher Henry Gauthier-Villars aka “Willy”, we meet an exuberant, wide-eyed young girl hungry for everything that the world had to offer and then some. Thanks to Willy, Colette was exposed to all of the intellectual and artistic circles of the day. She was also exposed to Willy’s libertine ways which led to her exploring her own sexuality, especially when encouraged by Willy. Avant-garde in every sense of the word, Colette truly found her literary voice when writing her first four novels between 1901 and 1903, ultimately known as “The Claudine Stories ” – “Claudine at School”, “Claudine in Paris”, Claudine Married”, and “Claudine and Annie.” Although somewhat autobiographical, Colette was ghostwriting the books for Willy, who not only forced Colette to write the books but then happily and greedily took all the credit and held the copyrights. But it’s because of Willy and his oft-wanton ways that Colette became the woman that she was; the woman who defied society and its constraints, the woman who revolutionized the literary world, the woman who explored gender issues and sexuality, the woman who challenged the male-dominated business world (and her own husband), the woman who became a successful author in her own right, the woman who became an icon.

In the hands of Westmoreland and Knightley, COLETTE comes to life. She is a vibrant force that goes beyond the cinematic canvas. Surprising is how light, and sometimes even a bit self-deprecatingly whimsical the film is. Westmoreland has a light touch with addressing all of the issues and themes which are still so prevalent today – gender identity, feminism, crossing societal lines of acceptance, individual identity as both a woman in her own right and as an equal partner with her husband, and then commentary on fashion, literature, the arts. And it’s that light touch which is what makes Colette’s story all the more appealing, welcoming, and resonant. So heavy-handed is the drumbeating in the world today, that to experience age-old issues presented in a very matter-of-fact in a casual manner within the lives of Colette and Willy, with the camera capturing the outcries of those around them as they “broke the stereotypical mold” of the day, is beyond refreshing and quite honestly, echoes more loudly. Unfortunately, Colette’s battles of the early 1900’s are still being fought today and are as prevalent as ever. The contemporary connection to this material is undeniable and it’s that different lighter voice that can be heard above the echoing roar of women today, thus making COLETTE even more impactful and telling.

Always transportive and transformative with period pieces, Keira Knightley is a breath of fresh air as COLETTE. Fun, freeing, fanciful with a sizzling and smoldering edge of excitement and naughtiness. She is electrifying to watch as Colette develops and comes into her own, becoming more than just “the girl with the hair”. Knightley’s facial expressiveness and physical movement are emotional extensions of Colette’s individual growth. And once Colette takes a stand with Willy and they have a “partnership”, the equal footing Knightley shares with Dominic West is easy to watch, and more than entertaining, as Knightley fills COLETTE with unspoken confidence and elan. Believable. Enjoyable.

As for West, he is delicious, embodying Willy with all the traits of a brilliant braggadocious self-absorbed blowhard but with a true love for Colette that goes beyond her writing the stories of Claudine. It feels as if West had FUN playing this role as he gets to cut loose and have some over-the-top playtime. Interesting is that the chemistry between Knightley and West feels more like brother and sister than husband and wife, so when we finally see the dalliances of each as they go their own way sexually, it is never jarring or shocking. It all feels completely natural and honest.

Supporting cast is equally good. It’s always a joy seeing Fiona Shaw. Here as Sido, Shaw’s performance is similar to that we see in “Lizzie” where she plays Lizzie Borden’s stepmother. Solid and grounded. Eleanor Tomlinson is exuberance personified as Georgie while Denise Gough owns the character of out and proud lesbian Missy, infusing a devil-may-care confidence into her making us believe that Missy is more than comfortable in her own skin despite what others may think of her; she doesn’t care what others think. And that’s one of the great unspoken themes of COLETTE – being comfortable with one’s self, being true to one’s self, and knowing one’s self, no matter who you are.

Hand in hand with the light touch of the story is the beauteous light touch of cinematographic maestro Giles Nuttgens. What a beautiful visual canvas he paints! The overall softness, especially with the exteriors in the countryside, not only captures that perfect European light, but also has that cinematic textured feel of shooting on film. The golden light of the palatial home of southern belle Georgie and her respective intimate rendezvouses with both Colette and Willy sets the tone for each of those scenes, but most appreciated is the visual distinction between those liaisons. The camera moves slowly over the bodies of Colette and Georgie as soft sunlight streams through chiffon curtains while when Georgie is with Willy, the camera is static in a perfect frame, lighting is darker and harsher. This exquisitely distinguishes between the type and meaning of each encounter: Colette is truly enamored and cares about the relationship she has with Georgie. Willy is a horny older guy. Colette’s country house is light and bright, open and airy thanks to Michael Carlin’s production design. Nuttgens relies on natural white lighting in the country house, metaphorically creating the idea of an open and airy life and lifestyle as opposed to the claustrophobic nature of city life. Within the city apartment shared by Colette and Willy, lensing is often shot through windows within the apartment – metaphor screams the distance and closed-off nature of the relationships amongst all; that there is always some sort of barrier as opposed to the freeing nature of life and companionship in the country. Absolutely fabulous visual metaphor throughout. Notable also is that many shots of Willy in the company of others are dutched slightly upward which makes him seem even more imposing, yet the bulk of images with Willy and Colette together has both on equal footing and also very close to equidistant eye leveling.

And applause, applause for Michael Carlin’s production design throughout. From the country house to Georgie’s salon to Willy and Colette’s Paris apartment to the theatre or the party venues. Each is as gorgeous as the next. Telling about Willy is the design of the Paris apartment with the narrow hallway that leads to the office and library of the lord and master Willy, with various rooms then offshoots from the corridor as if branches stemming from the tree trunk. Color and wood tones are masculine and complement the pompous and bombastic nature of Willy.

Adding to not only the cinematic experience is Thomas Ades’ score which also follows through with a lightness as a nice undercurrent to the story at play.

by debbie elias, 09/15/2018