As part of BEHIND THE LENS ongoing awards seasons coverage, we shine a light on the artisans and craftsmen “behind the lens and below the line” who are each an integral part in the collaborative effort of making a film over the past year. One would be hard-pressed to make determinations as to whom among them will win awards (we’ll leave that to the Guilds and the Academy), but one thing is certain – each is award-worthy in his or her own right.

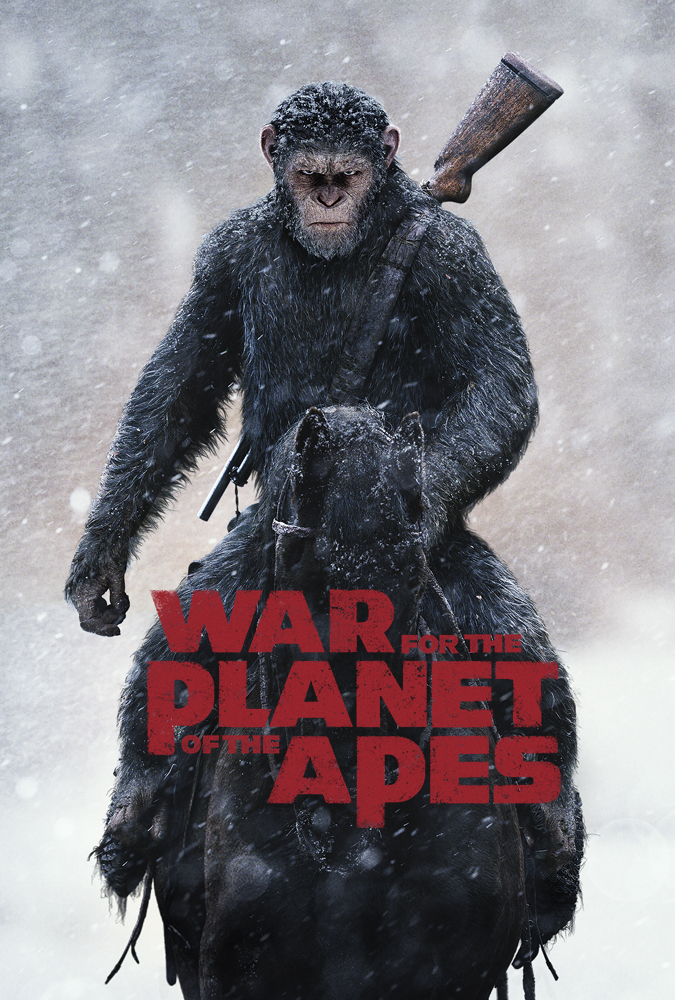

WAR FOR THE PLANET OF THE APES is a hot awards contender this year, not only due to the possibility of an Academy Award nomination for the film’s star, Andy Serkis, but because of the technical proficiency and excellence with its editing and visual effects in bringing the story to life. Speaking with WETA’s Dan Lemmon, VFX Supervisor on WAR, and BILL HOY, one of the editors of WAR, we learn about the synergy of the two departments to create not only a seamless visual flow and pacing, but to achieve the emotionality we see unfold onscreen which makes WAR a standout.

Giving detailed insight into the editing process on WAR FOR THE PLANET OF THE APES, editor BILL HOY goes in-depth with film critic debbie elias in this exclusive interview talking about the collaboration with the VFX artisans of WETA, benefits of 6K imagery, editing for emotional storytelling, the joys of Avid editing systems, and more. . .

I am so thrilled to get to talk to you. I’ve been a huge admirer of your work over the years, going all the way back to “Dances With Films” and then everything in between. To see what has happened, especially with this last trilogy, from DAWN, to RISE, to WAR, with Planet of the Apes, what I see in your work, and that of your co-editor Stan Salfas is, I see the editing of emotion that you brought in “Dances With Wolves”, but you still complement the action and now, the mo-cap technology. But so many editors, whenever you have action involved, or VFX, or mo-cap, sometimes they forget about the emotion that the characters need. You don’t forget about that, and if Andy Serkis gets his long overdue Oscar nomination this year, it’s going to be in part because of your editing.

Well, I thank you for that, but he deserves all the credit, because he is an amazing actor. I’m a huge fan of his, and it’s high time he was recognized for that. I think there’s kind of a misconception that the visual effects have helped his performance and all of that, but that performance is all his. I think we can show you a scene side-by-side, and what we try to do, which is to keep his performance. What WETA does, the genius of WETA is being able to translate his performance, a human performance, and make that a simian face, and have that emotion come through.

It’s spectacular. To see where mo-cap has come since the early days before Peter Jackson’s “King Kong”, how WETA has become involved, and how integral editing is with the technology and the storytelling, has just been a wonderful journey to watch.

Yeah, and I’m happy to be a part of this journey, too, because I’ve learned so much since DAWN. There was a steep learning curve on DAWN, but I think on WAR, we have a shorthand working with Matt [Reeves], and the ability to show him a cut very quickly, and take performances, to go through a performance and place it in the scene. Meaning these takes can be from, it can be from the same take, and even though they’re looking in a different direction, we can at least make that performance uniform, the strongest performance, and have that play out, even though his eye lining may not be right. We know that once we get done with that, he’s a three-dimensional character, and he will be looking the right way. There will be emotion in this close-up that was taken from a live shot that was only shot in mo-cap, and then it gives us the wide shot. It’s things like that that helped a lot on WAR, because it had been a very complicated process.

How has the technology changed over the course of these three films, that enabled you to enhance your own work?

Well, I think a big part of it is to trust that WETA, the visual effects team, would be able to accomplish that, but we were very in close consultation with them. We had our producer with us all the time, and anytime we wondered if we can actually accomplish the shot, we would call him into the room and discuss it with him, and see if there was any limits to what we could do. But on DAWN, when I began to put the picture together, the performance from all of the actors, Toby Kebbell, who played Koba, they had these scenes together. I just thought they were so amazing, and you already felt the emotion in the scene, but you already felt that they were actually talking apes, even though they were in the motion capture suits.

When we had the first tests come back, I said, “Oh my God, we get this, too?” Because it came back, and they were fully realized apes within the scene. When you see that, it brings us to another level of excitement while you are working, and then on WAR, they exponentially became even better at what they did, because they just built on all their software, and their artists, Dan Lemmon, who was the visual effects supervisor, and his team, they already knew what these apes are. They knew more about apes than a lot of people who work with real apes. They know everything about chimps, and simians, and apes. They’ve put all that knowledge into their apes.

When I read the script for WAR, I said, “This is in the rain. This is water on fur, and then they’re in the snow.” I’m like, “What else do they have in this picture?” But they accomplish that to a very fine degree, I must say. A lot of it is that trust that we’re going to ask for this shot, we want to put our hero, have him underneath these really dire circumstances, that he has to rise out of. If we’re able to make these conditions for the hero, and then he has to rise above it, it makes him even greater. He’s freezing to death, and there’s frost on his face, and it’s raining out. Whatever conditions there might be, he’s coming down the mountain and there’s a small avalanche, and he’s so hellbent on revenge that he’s just going down the mountain in blind rage. That speaks something to the character, and so these visual effects enhance his character and the storyline for us. We have a very close consultation with WETA when it comes to things like that.

I’m curious, because obviously you have to build up a scene, and I know the three or four primary shots every director, every editor looks for, and director, is a wide shot, a close-up shot, or an ECU and an over-the-shoulder. What kind of shots were you given to work from for each one of the scenes as you’re building them up? Was it a standard three, those three, or did you have like nine coverage shots to pick from, to try and start building up a scene?

Well, I would say that Matt Reeves, our director, his view of WAR was WAR might be one of those classic movies, say a David Lean movie, or a Sergio Leone movie, that anything in physical camera could not do, say when you pull back, and all of a sudden the tree appears in front of you, he didn’t want that. I would say a lot of that coverage was in a very classical form. Not a lot of steadi-cam shots. Certainly, there were a few, but they were more presented as the point of view of our hero. We did have very classical coverage over the shoulders, close-ups. Very, very tight close-ups, wide shots, moving wide shots, but at the same time, with this technology, we shot it in 65mm Alex and we had a 6k frame to work with, so we could blow up a shot as long as we had a background plate. What happens when there actually is a physical production, they shoot our motion capture characters in a remote location, like the rainforest in British Columbia. They shoot it with everybody in the scene, meaning that humans with the motion capture characters in the scene playing against each other on the physical set. But then they take away the motion capture actor, and have the human play the scene by himself or herself. Then they take everybody out, and then they duplicate the actual camera move with the crane. It’s called a techno-crane, and it’s just a computerized crane that all of the movement that had preceded it.

Now we have three levels of picture to work with. So, if we wanted to be tighter on a shot, we could actually blow into this digital negative many times over. I think we can blow up 100%, and that’s huge, without affecting the quality of it. We can change the coverage in the editing room, which we did a number of times because Matt’s idea was that it had to feel like we actually set the cameras up, and shot these apes talking to each other. Here’s the over-the-shoulder, and here’s the close-up, and we do have a wide shot, that looks like so. But the coverage didn’t look like that, so we had to manipulate the actual shot, and relate that to WETA. That’s exactly what we want. We want this over the shoulder. For instance, the performance could be from a wide shot or a close-up, but we wanted that close-up performance in the wide shot, so we’d have to take that particular performance from the motion capture character and put him in the wide shot, and ask WETA322ws1d to put those two pieces together. And maybe the wide shot is too wide to focus on our character, so we cut into it a little bit more. We can manipulate the frame in many, many ways.

How exciting is it for you that the Alexa 65 is delivering 6k images for you to play with?

It’s very exciting. It means that we can manipulate the images. I mean, I think one of the things about working on visual effects pictures like this is that in the frame, I can become, the editor can become a collaborator in what actually appears in the frame. Before if you shot the picture on a physical set, you got what you got, basically. We had very little ability to change that after the fact, but now, we can say what worked. Just because of geography, if I’m a little confused, if we put this post here, or we color this post a certain color, or make it distinguishable from other posts, immediately when we go back to that post, we understand that that’s the geography, and that’s where he’s standing. And so we know, that’s where the hole is, and that’s where they have to get to. It helps you with your storytelling, too, or how many apes are in the shot. They’re all arriving. What are they doing, exactly? And how does it happen? Is it one ape sparks it, or is it all of a sudden the whole place erupts? You have control of that to help tell the story, and I think those are the things that take place in the editing room. The performance of our lead actors is something that we absolutely want to preserve.

Something that you do so beautifully, and I think this is the peak of your career thus far, is shaping the story with character beats, and working through the performances and the emotion. It is evident in the editing, in the final cut, that as you were looking at these frames, you cared about the character, which then allows the audience to care about the character. How do you approach finding those emotional beats, say in contrast to how you would approach battle sequences which, rather than lingering shots or quiet shots, we’ve got a lot of cut, cut, cut, cut?

I think that they’re both related, in a way, because in a battle scene, if I don’t care about the characters that don’t have a point of view, then it is just chaos, and loud music, and loud sound effects, but to what end? Unless you’re just trying to show chaos, what point of view is it in developing a character you hope that carries through once you’re in the thick of battle, that you can just cut to one quick shot of our hero, or whoever that might be. That then tells us how he or she feels about what’s going on, or it might help the audience wade through what the point of view of the storyteller is about what’s going on here. Is war horrific, or are we glorifying it, or is it just through this character’s eyes? I think from the standpoint of finding the emotional shots from different characters that I watch in dailies, when I read the script, especially this script, I love this script because I didn’t know what to expect, but it was this journey of discovery for Caesar. All these things kept popping up. He is hell-bent on revenge, and then you meet this little girl. Now what are you going to do? Then they go and meet the bad ape, what a motley group this is. So the idea was, when I went into the dailies, that I would actually look for those moments that enhance the broader aspect of the story instead of that it’s just that moment, but there is that, too.

When I watched dailies with certain scenes, sometimes there’s a moment that really strikes me as, “This is really the heart of this scene here.” And sometimes, yes, I could be wrong about that once I put the entire picture together, and everything does change, but at that moment, there is something about that. When the picture begins to morph, and change, as we cut it down, and as different things become important, maybe that moment could be used for something else, but there was something about that performance that spoke out to me. It’s hard to have this very general, broad view of a movie when you’re in the scene to scene, but it’s important to keep that in mind. Why did I do that in the first place? Why did I like that in the first place? If it doesn’t work now, how can I use that somewhere else because there’s just something in those eyes, but it’s just an amazing performance and maybe we can have that reaction for something else. It’s finding those moments. I think when you see an actor in dailies, and they are being very truthful in their performance, then you know that’s really something special. If I can use that at all, I’ll try to use that.

A lot of people aren’t aware that you go through a lot of iterations, especially when you’re working with WETA and the VFX animation is coming in with the mo-cap. As you get the animation, after you’ve done your dailies with the mo-cap, and then you start getting WETA’s work fed back to you, how does that then impact your editing as your layers start coming in, as you get the animation? So you now see the apes, and then you’ll toss it, there’s dialogue, and then a temp score at some point that you put in. How does all of that start impacting how many passes you’re making, and the manner of editing that you’re doing?

We make quite a few passes because we might be in the editing room, and we work on a scene, and work out some problems, and we say, “Oh, that works now, but how do we actually show this first to an audience, much less just getting it to the final version”, because people look in different ways, and there might be thoughts and ideas in there that are missing because we’re missing characters that we need help from WETA. We actually go to a post-production team, which helps populate what we need to do, and maybe put temporary characters in there. Then, we will go pass it on to WETA, and explain to them, give them notes about what we think is important in this scene, and how they can help us, and then we begin to get these iterations back.

Next one is positioning, which is called blocking, and where the apes appear in the frame, and there’s very rudimentary animation. If we want over to shoulder, and we want to be the same as the over-the-shoulder that preceded it, and things like that and then we start getting the rendered shots back. It’s a process that takes quite a long time, and a lot of phone calls to WETA, but it’s not until actually the final version that comes in, and then we actually see all the emotions, how the light hits the eyes, and how the human girl looked at Maurice. At that point I found it so expressive sometimes that we can actually cut down on the shot. We don’t need this lingering look because these few frames tell at all. This is the high point of the shot. We can get out right here. We don’t need this, and that held true right to the final mix, where by the time we had the final mix we had most of our visual effects done, if not all of them, and we began to take score out because we didn’t need that enhancement. We didn’t need to tell the audience what was going on emotionally because the apes were so realistically rendered, and how they interacted with our humans, it didn’t need all that embellishment. We found scenes taking the sound effects out, or taking the music out, and just let the scene play. I think you’ll find that there’s some scenes that play in silence or very minimal sound effects. That was kind of the process through which we began. Because we started with basically temp music throughout the entire picture, but gradually began to lessen it, or have it less bombastic, say, so that we let our characters tell the story. That’s something that we actually don’t get the final dailies until we’re mixing. That’s kind of what it amounts to.

You’ve got another element in there with sound, that I believe impacts what you do when you’ve got your actual production sound. I know Matt’s a huge fan of using actual production sound, but production sound versus ADR. How does that impact your editing, if somebody’s got to go back in with ADR, or the production sound itself, if it’s contra to what ultimately the character-driven performance leads us to?

I’m a big fan of production sound too because sometimes it’s very difficult for an actor to come in and put him in that position again. It’s raining out, and it’s loud out. There’s all these other things happening, and there’s no actors for him to perform with. That takes some off their performance. That’s not to say that there aren’t some actors out there who are very good at ADR, but there’s something about the production sound, it’s a quality of the sound. What I normally do is to send that questionable soundbite over to the sound department, or sound team, and ask them to analyze, “Can we save this, or do we actually have to ADR this?” There are many ways to do it, but we prefer not to ADR, if we possibly can. But there are some places where we do have to do ADR to help fill in a storyline, to maybe help with exactly what the action is, and where they’re going, or what they’re doing, or what their intentions are. There is that too. One of the other things, this type of venture, the quality of sound on the physicals set is quite different, but we shot for basically a month, five weeks, maybe more on a motion capture stage. Some of the sound will just flow in there, so we look to our sound design team to make the dialogue flow very smoothly with the rest of the dialogue that was shot on a physical set.

As an editor, especially with this film, since Matt really pushed the boundaries of going into snow country, and rain, we all know, number one, how difficult snow is for cinematographers. It’s also very difficult for editors, but here you’ve got snow, you’ve got rain, you’ve got fur, you’ve got mo-cap. For you, do you prefer having the real set with all of those real elements, or the virtual green screen stage set?

If it’s raining, I prefer it to be raining lightly, for a lot of technical reasons. One, the sound, but if it’s raining and it’s actually wet out, we can augment that by making it heavier rain. But if it’s really heavy rain, and then it lets up, then it doesn’t match from shot to shot, and that’s something else. That plays into just the technical aspect of it. For me, editing-wise, if I were to just look at a scene, again, I do think that the physical aspect of it plays on our actors, too. Whether they know it or not, they’re pushing against the rain, and they’re blinking. All the action is just more natural, say. If you’re on a green screen set, you can tell them it’s raining, it’s raining hard.

But the actor will most likely will carry that physical enhancement throughout the scene. It’s like I said, we have our human actors interacting with our motion capture actors, and I would say most of the time we find when we take the motion capture actors out and just have the human actor play out the scene, even though the motion capture actor is calling the lines offstage, that performance will not be as good, and spontaneous, and truthful as with the other actor in there. It’s as simple as having two actors in a scene, playing off of each other. I think that probably holds true for the elements, too. I mean, they’re trudging through snow, and this is really deep snow, so you have to trudge through deep snow. What does that feel like? Maybe as an actor that grew up in Hawaii or something, you’ve never been in the snow. You don’t know what that is. Those things are actually in the physical condition. For me, I think it just looks more real, but very lightly, I might add, to enhance the visual effects.

Did you have the luxury of actually being present on location, or on the stage for the filming? Because as you’re doing dailies every day, I’m trying to envision you running between set, running between editing bay. Did you have the luxury of being able to actually be on set?

Very rarely I go out to the set, just because a lot of times they’re shooting in these locations that are out somewhere in some provincial park in British Columbia, it’s very difficult to get to. It’s an hour there or more, and so if I take the time to go out there for an hour, drive out there for an hour, then spend two hours there and come back, that’s half my day. I can’t afford myself that kind of time, but I have on both pictures, both DAWN and WAR, gone out to the physical set and see what exactly they’re up against, and it’s pretty daunting when you’re out there in the motion capture suits, and it’s raining, and they have all these huge camera equipment to move around. You say, “Okay, turn the cameras around, and I’m going to shoot the other way.” That might be the next day because there is so much equipment attached to it because it’s motion capture.

But as far as the motion capture stage, a lot of times that’s located very close to the editing room, at which point I try to visit the set every day, and see if Matt needs something, or if he needs a scene that they’re actually augmenting, or he needs some reference that I have, or whatever it might be. I’m in much closer consultation with Matt, our director, at that point. Especially when we’ve set aside three weeks of motion capture photography after the principal photography on this picture, and that was because there were some scenes that were virtual sets that weren’t ready to shoot at the time we were shooting. So, we pushed that later so we understood exactly where they were. Those were shot after we finished principal photography, and I was on the set for that all day. I mean, we actually had our Avid on the set, so we were right there, because a lot of those scenes were shoehorned into the existing cut, say. Some of them were very important, as transitions, and sort of things that flow smoothly in and out of scenes. At which point, I’m there, but I have my Avid with me, and I’m not working off a little laptop.

How fun is it to have Avid at your fingertips?

It’s a great tool because there are so many things that we can do. There’s obviously the speeding and the slowing, but I can do quick comps, just to explain to Matt exactly what my intention is here, if I present him something that he hasn’t seen before, or we can comp it in and pass it on to visual effects editors, and they can do a much better one at that point. I can take different pieces, and layer it all on the Avid, and music and sound effects. I mean, there’s so much we can do with the Avid. It’s just, how much time do you have? That’s the way it goes, too, because I can sit there and cut out the outline of a human, and place it in the shot, but to what end? Because that’s not time that I should be spending, I should be spending time realizing the whole picture. But I’ll just take those two elements, and pass them off to one of our digital effects editors, and they will then cut it out and place it in there. Then it’s, “Oh, okay, that works,” or, “Just move it over a little bit more to left.” It’s a very good tool to us. It helps us to tell the story, especially on pictures like this, visual effects pictures.

Is there another editing tool out there that can really deliver to you what Avid can give you? I go to NAB every year, and I look at all the toys, and Avid is always the standout with all the bells and whistles. Like you said, you can take time, and you can cut out a human shape, and you can move it around. Is there anything else that is even comparable to this level of filmmaking?

I haven’t investigated them all. I do have Adobe Premiere, which I haven’t played with much, but I have used Final Cut, the previous version. Not to denigrate Final Cut, but I just find it cumbersome for what I need to do. Plus my assistants say that for how we work, on War we had probably 12 or 13 Avids going at one point, all feeding off the same information. My assistants tell me that a system like Final Cut could not hold that many systems at one time, and the idea that if I was working on a certain scene, and someone opened that scene in another place, that I wouldn’t know the work had been done on it. I think just the coordination of the workflow would be more difficult as well.

I used [Final Cut] only on a very small project, so this is a thought. I want to make this trim, but I don’t want to trim everything right here, and I want to trim the sound down here, or mute something here. You have to do this, or you have to cut this, and then go down to pick up, wait, there’s not a button I can? No, it’s those kind of things. I think it was designed by software engineers. Actually, it’s probably very good for people who use it in different ways, but I think for feature films, it’s not. There hasn’t been anything that’s come into my view that is something that I would jump to. I’m willing to try Adobe Premiere Pro. Like I said, I have it in my laptop, I just haven’t had a chance to actually go and spend a lot of time with it. There’s a lot of toys. They continue to put different things in the Avid. They upgrade the software all the time, and I wonder, why did they do this? I don’t understand. You know the Avid quite well, it sounds like, so I don’t understand. Why did they change this? Who needs that hidden somewhere? I need that right here. It’s things like that, I don’t know who did that.

Unless it’s something really simplistic, just a two camera thing, just dialogue, throw in some score, I think Final Cut is fine. But for anything this massive, I don’t think there is anything that can beat what Avid delivers.

Yeah. Again, especially because we have so many systems feeding off the mainframe, just the coordination of all that workflow would be a nightmare. I mean, sometimes we have deadlines to meet, and if something inadvertently changed somewhere, I wouldn’t know it, and that would be horrific. That would cause so much financial pain down the line, so we can’t have that.

Two questions before I let you go, Bill. This is such a joy talking to you, by the way. This is so much fun. I wanted to ask you about lighting. Matching up lighting everyone thinks a cinematographer’s job. But here, because of your mo-cap, you’ve got your background, and you have your live-action. How does matching up lighting and reflection on faces, how challenging is that for you in the editing process? Or is that something that will just fall to WETA, or is it a combination between the two of you, and to get, for example, a flashlight. The flashlight is passing over, and it’s passing over live action and it’s passing over apes, mo-cap. How difficult is that, to get that synchronized so that it is a seamless ebb and flow?

When they shoot the actual shot, they go in there with the reflective balls, and they record all of the light from the set, how it actually played out. Matt is the one who, he’s very, very particular that certain shots were not overlooked, but they look the way they did if they actually shot the apes. Or how it actually played on, say, Andy Serkis’s eyes when he was in this close shot, riding on a horse with the shadows of the trees behind him. With all this reference, if it was slightly different, we would call attention to that and tell WETA, “We know you want to show the eyes, but in this case, we actually don’t need to see them because first of all, not, we don’t need that for the emotion of the scene, but it’s actually even better if we just see it slightly for the emotion of the scene.”

That’s how it existed in the actual, physical production, but we can also take license, and if we wanted to, we could just get it just a little bit. But then when it comes to, say a scene that there is no reference, and WETA’s lighting it, then we try to find something in the shot that tells us where the shadow is, and how our apes will stand out in there. If they’re over lit, they just feel like they’re the visual effects characters, they’re CG characters. I think the real, one of the things about making these apes look real is the actual lighting, and what it seemingly would look like if they were in, on the physical set itself. We do have control of that, and sometimes we take a little license with that. They have like a God light come in, and make the shot a little more ethereal.

We do things like that, but that’s when the actual realism of the shot is thrown out, and we’re going for some other aspect of a shot to help tell the story.

So now the film has been out there, it’s getting ready for its Blu-ray release, the awards campaign is going full speed ahead now, what did you, as you sit back and reflect on this film and all of the elements brought into it, what did you learn about yourself, and take away from this experience that you’ll be able to take with you into your next project?

Well, I think the idea that the most important thing, the thing that hasn’t changed, really, with all this visual effects ability available to me is a good story and characters. To confirm what I, as an audience member, and as a film editor believe in, is that when I go and see a movie, I want to see a good story. I want to be emotionally involved in the characters, and being able to work on a movie like WAR, where almost all of the visual effects budget is devoted to performance. That’s a real thrill for me, and that doesn’t happen very often. What I get is that I’m able to use the technology, and use this innovation, and grow, and learn as a film editor, and that’s been given to me, the opportunity has been given to me, so I’m very grateful for that. I can take these ideas, and move on to other pictures, and maybe help populate a scene like we did with the APES series, not with apes, but with other things. It helps with my imagination. We can do that, or we can’t do that. I think that experience is now inseparable from what I see the possibilities of a film presented to me, and I think, “We can do this. We can do this. I’m not sure about that, we should ask about that.” But I think we can help the scene by doing this, and it’ll make our hero stronger, or it’ll make them weaker if this happens. It goes to the storytelling aspect of it. I don’t think anybody should be afraid of this technology. It’s a way to enhance storytelling, from where I see it.

Do you have anything else lined up now, Bill, or are you taking a well-deserved rest?

Well, I was taking a rest, and then some producer friends asked me to come on and help on a picture that’s called “Underwater” right now, but they’re going to change that title. There’s visual effects in it and most of it takes place underwater. It’s about man drilling to the bottom of the ocean for resources in the near future and it unleashes all kinds of calamity. Being underwater is another element and I can draw from my experience on the visual effects. What do we see? How can we help this geography? How dark is it there? How big are the creatures? How fast do they move? This kind of thing. I’ll be on that for a little bit, but I’m looking forward to just a bit more time off before I go on to a little more long-term project.

by debbie elias, interview 10/01/2017