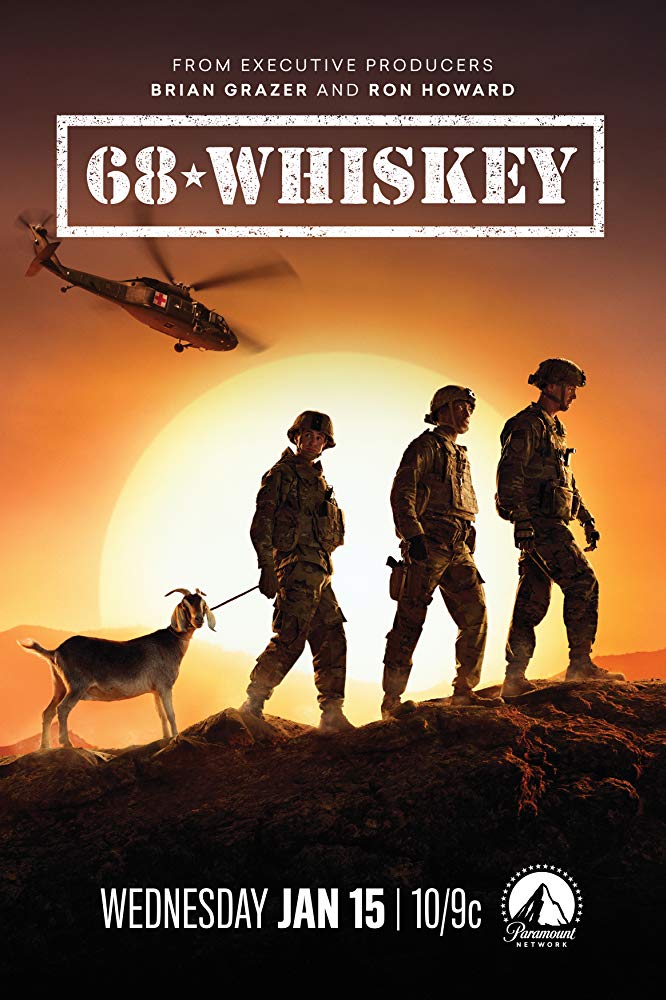

Television has long celebrated our men and women in arms during wartime. We’ve seen the slapstick humor of “McHale’s Navy” and “Hogan’s Heroes” tackling two fronts of World War II, the Pacific and life in a German POW cap. “China Beach” provided a dramatic look at Vietnam from a female perspective. M*A*S*H, one of the most beloved television series of all time, took us into Korea with the heart and humor of the 4077th. And now, 68 WHISKEY takes us to present-day Afghanistan and the men and women who serve as Army medics at Camp Orphanage. Ironically, just one look and listen to a cast of characters like Roback, Davis, Alvarez, Petrocelli, Holloway, Colonel Austin, and Sasquatch, and we are vividly reminded of the hijinks of Hawkeye Pierce and company in M*A*S*H but with the increased danger, technology, and political manipulations and machinations of today’s world. 68 WHISKEY is, to be blunt, M*A*S*H for the 21st Century, and is a very welcome and timely addition to the zeitgeist and the Paramount Network. But finding that perfect balance of comedy and tragedy to produce a quality show that speaks to the viewing public requires a skilled eye and skilled timing both in front of and behind the camera.

Starring relative unknowns as the principals of 68 WHISKEY, among them Sam Keeley (Roback), Jeremy Tardy (Davis), Nicholas Coombe (Petrocelli), Cristina Rodlo (Alvarez), Gage Golightly (Durkin), Lamont Thompson (Col. Austin), Beith Riesgraf (Holloway) Derek Theler (Sasquatch) and so many other ensemble players, only six episodes in and the show has legions of fans already looking for Season Two and beyond, thanks due to sharp writing from showrunner and creator, Roberto Benabib, authentic production design, dynamic cinematography, heartfelt performances, and characters in whom we have quickly become invested. With each episode we peel back another layer of camaraderie and friendship while learning more about what makes each soldier tick and who they are deep down.

Not shying away from the tragedies and brutality of war, with 68 WHISKEY we are met with a warzone naturalism that requires comedy and hijinks to offset the tension of the Afghan region, the ever-present Taliban, and even the corruption of crooked politicians with global side deals in play. While the story is on the page, walking that fine line of blending visuals with story is what makes 68 WHISKEY as engrossing and engaging as it is. Every episode has more than its share of moments that speak to the human condition and emotionality of being in the volatile and uncertain situation of a war zone, yet finds time to show us the best of humanity amidst the insanity of war and still keeping the audience on tenterhooks with riveting, tension-building scenarios unfolding both in Afghanistan and on the homefront. Finding that balance within each episode and establishing a cohesiveness within the series as a whole falls to the accomplished editing team of 68 WHISKEY.

For more than 25 years, editor IVAN VICTOR has been a constant force in the world of post-production editing. With a sense of rhythm and timing essential to any successful editor, Victor finds that sweet spot with pacing and storytelling, be it for a series like “Reno 911!”, a reality-based free for all like “Jackass”, or fun-filled thematic series like “1600 Penn” and “The Goldbergs.” And now he turns his attention to the perfect meld of comedy and drama with 68 WHISKEY as part of a collaborative and cohesive editing team.

I spoke with IVAN VICTOR at length about his craft and 68 WHISKEY. Articulate and knowledgeable, and with a charming sense of humor, Ivan is nothing if not passionate about every element of the storytelling process through editing. From the ebb and flow of the camera to focus on eyelines to perfect pacing for holding a shot or a joke or a poignant and dramatic moment, he speaks candidly about the process and the joy and satisfaction in his work, because at the end of the day, without the editor all you have is a “pile of footage.”

Ivan, I am a huge, huge fan of 68 WHISKEY. For my money, this is M*A*S*H for the 21st century. And like M*A*S*H, editing this show is so key to its success, to the understanding of it.

Brilliant! That’s lovely to hear.

We have similar relationships and situations, but we’ve got more drama with 68 WHISKEY than we’ve seen probably since the days of “China Beach,” which was set in the Vietnam era. But there’s a great balance between the comedy and the drama here. And one of the things that strikes me with 68 WHISKEY is the difficulty of finding tonal balance. Typically when you have comedy, people want to cut, cut, cut, cut, cut to get all the comedy in there. But you have so many beautiful moments in the first four episodes of yours that I saw before speaking with you, where you let the moment rest; you let the silence take hold so that we can appreciate the moments. I’m curious, for you from an editing perspective, how do you find that balance?

Well, a lot of the times it’s tricky because part of the system of TV is that it’s a very fast-moving process, especially with a show that goes straight to series. But I will say a lot of it comes out of the notes process, with both the studio and Imagine and the network [Paramount]. We’re all working together to make sure that we’re servicing all those moments, and it’s just a case of experimenting with, do we pause a little bit before we move from the drama to the comedy, do we ease back into the drama once we’ve had a comedic moment? There’s a lot of trial and error with taking out lines that are maybe too funny that would then undercut the dramatic moment that we’ve just had, especially in the pilot. We were really establishing our characters, especially with Roback who had a ton of amazing quips and all delivered beautifully, but we realized that if we took five of those out, then it allowed both of those emotions to play as well as they could.

Roback is a fascinating character who has so much underlying baggage that I suspect is going to be playing out even more as the series progresses. But we see his flaws and that’s one of the beautiful things that your editing allows. Nobody is lily-white. Everybody has flaws. Everybody has a backstory, right down to Colonel Austin who has his own You’re letting that naturally come out in a very naturalistic, organic fashion with this editing. I don’t see it as formulaic. So many shows we open with a wide shot, we start going into a medium shot. We’ll do coverage, coverage, closeup, closeup, back out. It’s very predictable. I don’t see that predictability, here.

That’s true. Part of the aesthetics that was established at the beginning with the British director, Michael Lehmann, and with Roberto [Benabib], and I know Imagine were very keen on this too, was to try and make this as cinematic as possible, even though it’s a TV show. Setting it in what effectively is the countryside in Afghanistan means that when we go out we have these beautiful wide vistas. There was a real desire to have lovely flowing camera moves, and to have a flow to how the show is presented visually. It was very ambitious in that regard. Having that as an aesthetic helps you to not get into the pattern of, as you say, wide to medium to close, with the occasional insert or a move, here and there.

I’m glad you used the description of, “a flow.” Number one, the show is very cinematic, on every level, this show is extremely cinematic. But that flow, and I see it when we’re up in the chopper, when they’re up in the Black Hawks because while the helicopter has its ebb and flow in the air, we also have an ebb and flow of the camera, of the editing, that follows that pacing. So I find that really interesting, and it’s actually quite soothing so to speak. It stands out to me as I watch it in that those are actually some lighter moments until, all of a sudden, they have to pay attention. In which case then, the camera shot holds and you hold it through the edit. You don’t go back and forth to catch the joviality and the insanity of Roback and Davis. I really like how that plays, visually and emotionally.

You’re right.

How many hours of footage do you have to cull through per episode, to get this down to its running time, of about 45?

Well, these are eight-day shoots. I gave up counting how many hours of footage I have, quite a while ago, because it just upsets me sometimes, to think, “Ah, there’s this mountain.” So I try and just go scene by scene, moment by moment. But there’s a fair amount. The thing is though, it’s a super ambitious show, and the actors are so good which is amazing, which means that the directors come in with a plan, they execute the plan and they move on. So it’s not like some of the other hour-long dramas I’ve worked on where you’ll maybe have 10, 12 setups for a scene because the camera hiccups around the room to get you new, different interesting shots. The directors who have come in have been very specific in what they’re looking for and while we are in a TV medium where you need coverage to enable you to take a 48 minute cut down to 44, it’s not a ridiculous amount of footage. And again, the actors hit the target most of the time, which is incredible. It’s an amazing cast to work with.

This cast is incredible. It’s an embarrassment of riches for not just the show as a whole, but for you as an editor. And I suspect it comes down to probably killing your darlings sometimes in the editing bay because as cohesive and beautiful as everything plays onscreen with top-notch performances, I can’t imagine they’re giving you anything that you don’t want to keep in.

Pretty much. Occasionally there’s the odd flub, there’s the odd moment where a performance isn’t great, but there is always great stuff to choose from. And the casting and chemistry that everybody has is pretty special. And I think part of what makes that work is that there are no massive stars, yet, in this cast. They came to this very fresh and were so appreciative of the opportunity and the quality of the production, and the quality of the writing, and what they had to dig into as actors, that they just bring the goods every time.

And this is also a very timely and topical show, too, with a lot of the messaging that we’re seeing.

Yeah, for sure. And it doesn’t shy away, as you mentioned too, from the fact that these are imperfect human beings who have problems that hover over them and put weight on them in this very high pressure situation.

One of the most charming characters who’s emerging in this show, and you captured some of the most precious moments, is Nicholas Coombe as Anthony Petrocelli. Petrocelli, and the goat, has such lightness and such sweetness. I notice that every time he’s lensed with the goat, the camera comes in closer, for the most part, except when they are all trekking. But the sun is bright. There’s never a dark room. It really just lightens the entire segment. And I can’t tell you how much I appreciate that, and the way you just let those scenes just sit.

The goat is a star, as well. I forgot to mention the goat, so I need to apologize to the goat and the goat’s representatives. Part of what you’re saying plays into one of my general aesthetics with editing, if I can get away with it, which is if the camera is doing its job and the actors are doing their job, unless there is a real necessity to make a cut, I will always err on the side of, “Let these incredibly talented people and everybody behind the lens creating the moment for them to exist in, just let that play.” Editing, as you well know, isn’t all about cutting. It’s about choices, too. And sometimes the choice is to not interrupt the flow and construct a moment even though oftentimes when you are immersed in the story, it doesn’t feel artificial. I think there is something that when there is a cut, on some level it feels there’s a manipulation; not necessarily in a bad way, but you feel there is a hand there, making a decision for you.

Very much so. And the cuts that you have in 68 WHISKEY are organic. It’s very natural because we’re shifting from the POV of Roback, Davis, and Alvarez and going to the POV of Petrocelli. Or, we’re going into the operating room with Holloway. It’s not like we’re taking away from some action. You’re letting each scene fade to its natural conclusion. Then you move us to somebody else’s POV as to what’s happening so everybody’s getting a fair shake. And we keep learning about each character in the mix. I never feel manipulated with the way that you cut this. It truly is very natural.

That’s good. We’re doing our job properly.

How much responsibility do you feel, Ivan, as an editor? Because as everyone knows, be it film, be it television, editing is the last line of defense for getting the vision of the product right and getting it out there. A lot falls on the editor, in that respect.

For sure. I certainly, I feel it. But I enjoy it, too. I don’t know if “honor” is too much of a word, but it is certainly something to feel like, from the initial idea through the writing phase, prep, after all of the struggles they have to shoot, especially on this show where we began production in September so there were some very short days due to the fact that it got dark, you do have the weight of everybody’s labors and sweat and passion falling upon you. And one of the things that is great on the show, is Roberto Benabib, the showrunner, is one of those showrunners for whom post is their favorite part of the process. So it’s great when you have people who come in and say, “You let me know if there are any problems. I don’t want any stress to fall on your department.” And he comes in, knowing that they’re coming to their favorite part of the process.

How closely do you work with the individual episode directors? Or do you primarily work with the showrunner and then get feedback from Imagine and Paramount?

The directors on an hour-long show get four days for their cuts. So we’ll have, typically, it doesn’t always happen this way, but typically, you will as an editor have four days after dailies to get your cut together. And our cuts are fully papered with background sounds and key sounds if we need them, and the music in them, as well. But typically, the director is entitled to four days and after that, Roberto or whoever the showrunner is, will come in and have a couple of days. Then it goes to the studio. You come back, you address their notes. Then it goes to network and there’s normally a couple of rounds of network notes. But in TV it’s the showrunner’s medium, and certainly on this show because Michael Lehmann is our producer-director. He’s involved in giving his opinion on how various cuts work and helping with the visual side of things in terms of color and sound. But it is, from when the director releases their cut, it’s pretty much all with the showrunner.

I know there are some television directors out there who like to have their hands in the entire time with the editor and who are very, very vocal about what they want. So I am curious with this particular show how that was working. I have to say that Paramount, between “Yellowstone” and 68 WHISKEY, are knocking it out of the park with creating cinematic, episodic television.

Yeah. They seem to really know who their audiences are, as well, and they’re working towards that as opposed to some people who perhaps have their own aesthetic and be damned whether the people who actually watch the channel like what you’re giving them. They’re pretty honed in.

You have done some very broad comedies and edited shows like “Blunt Talk,” “The Goldbergs,” and then you’ve gone way out there with something like “Reno 911.” But 68 WHISKEY feels like the perfect blend for editing. For yourself, Ivan, do you prefer cutting a show like 68 WHISKEY that has some drama and some comedy? Or doesn’t it matter? Do you have a preference?

Not hugely. I prefer if there’s comedy in it because it’s just great to laugh at work and to hone those moments. I enjoy both aspects because fundamentally a comedy is just a drama with jokes on top of it. So you’re always looking at storytelling as the foundation. And then it’s a case of making the jokes work. So, I’m happy with either.

How many cameras are used to shoot 68 WHISKEY?

Most of the time it’s one or two. And then occasionally, in the finale there’s a big, I’m not going to say, but there are a couple of big scenes that required three. But a lot of the time it’s just the single camera. Occasionally there’ll be some cross coverage, especially when they’re chasing light, but in order to get the kind of eyelines and angles that we’re looking for most of the time it’s just a single camera.

I appreciate that you just mentioned eyelines because we are constantly in the eyeline of each character when they’re on screen. They are looking at us. We’re not a fly on the wall in the ceiling. There’s no dutching of cameras. We’re not coming in for a crane shot, zooming down. The way this is show we feel like we are there with them. And I think that’s very important for this show.

Agreed. And that again I think tails back into the work that Michael Lehmann and Roberto did, but especially Michael, in making sure that while there is a flow and we do realize that the camera is a storytelling tool, it is used very specifically in a way that works organically with the narrative as opposed to, “Oh well, I can start with everything upside down and back to front. And I can twist the camera because we have a techno [crane] on set, every day.” Things are done with purpose, as opposed to someone thinking, “Oh, I’ve never done a shot like this before, that would be cool.”

What editing system do you use for 68? Avid?

Yeah.

What is it that makes the Avid system so good for this show? Or is it just that you prefer Avid? Avid is spectacular, as far as I’m concerned, but I know a lot of people are trying Adobe and some other software right now, so I’m curious on your take.

I came up learning Avid, so my system with how I organize dailies and how I work, truly the whole process, is based on how I gained my experience and my chops as an editor slash storyteller, is through that piece of software. I know one of the big advantages is, especially up to a couple of years ago, all of the file-sharing, which I understand. I know Premiere has been working on that, but… I do know there was a show that somebody did a couple of years back where they went on Premiere and the file-sharing didn’t work on that system, so if you wanted to give a bin to someone else, you had to copy it and give it to someone else, and they have to then copy it over. And it would take five minutes to open and you couldn’t just say to your assistant editor, “Hey, here’s something in a bin for you, can you fix this, this and this?” And then they do it, and give it back to you. So I think a lot of the technical workflow aspects of Premiere doesn’t really lend itself to a show with, we have three editors and three assists. There’s that Joel Goodman and Scott Wallace who also edit on the show and we’ve had a wonderful, collaborative experience with each other. They’re lovely guys and supremely talented editors. There are often times we’ll collaborate and ask, “Hey, what do you assume out of this scene? How do you feel that?” It’s been a wonderful experience, from that perspective, as well as with the whole post department.

I have to say Episode Five, “Pain Management”, which Joel [Goodman] edited, you talk about dramatic and action-packed! But still finding a couple little comedic moments in there, such as, “Did they get the Starbucks truck?”, was perfectly timed and placed, and a perfect scene to lighten the trauma of what we’re seeing, with some of our own being injured and hurt and killed, by the attack. Joel did an amazing job. And it fits perfectly with what you had already established in the first four episodes, in terms of style. It’s beautifully done. Seamlessly done, back and forth, with you guys.

Right. I did one and four, and Scott did two. Joel did three, so we kind of ping-ponged along. I always find it interesting too, because we all have different styles and different aesthetics. But the spine of how the episode looks is through Roberto. Roberto is incredibly respectful of what his idea is and what we think individually, as editors, that will work. Obviously, if something doesn’t work for him, he’ll pipe up. But it’s kind of interesting when you watch other episodes, there are some editors who will cut to the next speaking person, three seconds earlier, people will pre-lap and post-lap in in different ways. Yet, you still feel like it’s a consistent storytelling. That’s not something that we sit around and discuss, those light specifics. But I think it’s just the alchemy of how we all watch each other’s work and we watch the episodes and we make sure that we’re all cutting the same show, as opposed to cutting the way we’d like to do it.

I’ve just got one last thing to ask you, Ivan, and that is, why editing? Why editing for you? What is it about editing, what is the gift it gives you?

Oh, God! I get to be by myself a lot of the time. I really enjoy that. Not that I’m a misanthrope in any way, but I do enjoy the amount of time where I’m just left to my own devices to create. And then there are these moments of collaboration. And when you drill down and hone in on the people you like to work with, it’s lovely to have great collaborators who come in. I find the whole collaborative experience to be great. My assistant editor Jessica is wonderful, and we have a great laugh and a good relationship. I always like it when people appreciate editing because we are, in a way, locked away in dark rooms, and editing is, I suppose, the invisible art. So it’s nice that there are people who acknowledge the role. Without it [editing], you just have a pile of footage.

by debbie elias, exclusive interview 02/18/2020