By: debbie lynn elias

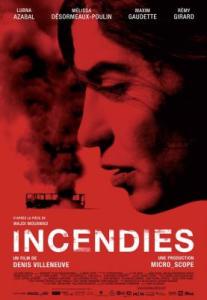

Adapted from the highly successful, powerfully moving play by Wajdi Mouawad, Canadian director Denis Villeneuve brings us the Oscar nominated INCENDIES – an enigmatic emotional powerhouse with a beauty and bold cinematic excellence that propels the tension, the love, the hatred, the understanding, compassion and courage of one woman and her family, to new heights, guaranteed to move even the hardest of hearts. Written and directed by Villeneuve, thanks to a tightly structured narrative, exemplary performances, particularly that of Lubna Azawal as Nawal, and polished cinematic values, INCENDIES is an amazing and eloquent movie-going experience that will resonate with you long after the curtain falls.

As if the death of their beloved mother, Nawal, isn’t enough, at the reading of her will, Nawal’s twin children, Jeanne and Simon, are dealt another blow – the delivery of two envelopes by Lebel, the notary/probate attorney representing Nawal’s interests. Making this more shocking than stunning are the addressees of the envelopes – one, to a brother they never knew existed and the other, to a father long believed dead.

It is Nawal’s wish that Jeanne and Simon find their father and brother, completing a family history and circle of life long thought lost. Jeanne not only wants to fulfill her mother’s dying wishes, but is intrigued and curious, filled with unanswered questions concerning her life and that of her mother. Simon, on the other hand, is unfeeling and uncaring over his mother’s instruction and request and could care less about a father or brother. He does, however, care about Jeanne, and although he tries to resist joining in the search, cannot resist her pleas to help.

Aided by Lebel, Jeanne and Simon head to the Middle East for the adventure of a lifetime. What the journey brings is a new understanding of the woman they only knew as “Mother” as history unfurls with each new step, the outcome of which will make you gasp for breath in disbelief while your heart stops along with those of Jeanne and Simon.

I recently had the privilege to speak with Denis Villeneuve for an exclusive interview on INCENDIES. Humble, passionate and dedicated to the art of film, talking with Villeneuve is like watching one of his films. There is an honesty and truth that speaks from the heart, drawing one into his aura as being drawn into a Villeneuve film.

I have to congratulate you on a brilliant, brilliant film. It’s so moving, so astounding. By film’s end, you have to just sit there and gather yourself for a few minutes. I knew nothing about the film or the play prior to screening it.

Thank you very much. You are very generous.

When you saw this as a play, what was it that spoke to you and made you realize that you had to make INCENDIES into a film?

I think that you’re talking about your reaction after the movie. I did have a similar reaction with the play. I was totally astonished by how the play was performed, and how the story was powerful and beautiful. The play is four hours and it was like five minutes in my perception. It was such a powerful story. I was amazed how Wajdi [Mouawad] was able to talk about anger inside a family, inside a society from this really poetic Greek tragedy. To take this story’s point of view, I thought it was just brilliant. It is very uncommon, as a filmmaker that I am hearing that this is such a great story. I was not looking for an adaptation at that time. It’s not that I didn’t think I would make an adaptation one day, it’s just that I deeply fell in love with INCENDIES. I never thought about it. I just wrote straight from the heart. When I was out on the sidewalk going out of the theatre, my wife looked at me and said “Oh no. You’re gonna make a film.” And I said, “Yep.” I was totally astonished.

How challenging was it to adapt the play to a screenplay?

Right away, Wajdi, the author gave me total freedom. He gave me the freedom to do whatever what I want. “You can just take the title. You can just take a scene if you want. Take a character of the story and make it your own. I give you the right as long as the movie comes to you. I knew that no matter what [you] would do, the movie belongs to you, even if the movie is a total failure.” It was a beautiful, artistic gift so it was very important to have that kind of freedom in order to make the adaptation because the truth is, I changed a lot of things. I kept the main characters and the same story, of course, but I did have to remove all the beautiful and powerful theatrical images that was on the stage because, as I said, they were very powerful and beautiful but so theatrical. The main problem for me was to deal with the fact that I would put the story in a fiction land like the play did in order to stay apolitical. And at the same time, for me it was a big challenge to talk about Arabic culture. I think it was very important for me to have a great amount of image in front of the camera. That was my main challenge because, of course, it is not my culture. To shoot something that you don’t know is a very bad idea for a film director. So we made huge research and made several trips to Israel Jordan in order to understand this culture. I put my views aside and asked a lot in order to be able to bring a portrait of this culture in front of the camera.

I find the timing of the release very interesting considering Julian Schnabel’s movie “Miral” was also recently released. Now “Miral” is specifically identified as belonging to specific countries and has raised a furor of protests. Have you, as yet, using a fictional country in INCENDIES, encountered any protests over your film?

It was not about the protests, but more about the fact that the movie was about peace. When you deal with this part of the world with those territories, if you want to make a movie about peace and you want to be apolitical, you want to be neutral, in order to be able to talk about anger without creating anger, it’s quite a task. This story [INCENDIES] is so complex that already the story is enough complex without talking about the politics. The difficulties of civil war is a very complex part of history and it was not possible to have any view about it. For me it was very important that the audience was aware that I was making a fiction film. As I said, in order to make it apolitical, I had to make it in a fiction land.

You said that you had to take away some of the theatrical of the stage.

It was beautiful, so beautiful on the stage, but impossible in front of the camera.

You have great beauty in front of the camera with the story and with the visuals and the emotion that you create with your cinematic elements. A lot of that is with the lensing. You use some very intimate shots – close-ups and mid-shots of two people – and you balance that beautifully with establishing scene shots that provide the parameters of the situation.

Exactly. You’re right. The way I was able to get inside this story because it’s not my world – its talking about something that I know, which is family and intimacy. That was my door for the story. It was very important to stay always from the intimate point of view from the victim’s point of view and be very close to the character in order to always be in their point of view. My goal was to be able to show landscapes, staying close to the character. That’s why I used a lot of Steadi-cam, which is a very fantastic narrative device for such a film.

It really works perfectly for you. With your wider shots, your panoramic shots, you set the scene and it works very well when shifting between different time periods. But then you held onto that intimacy with your close-ups. You make it feel like the audience is right there with the character.

It’s also a way for me to be humble about war. I don’t know war at all. It’s a reality that is very far away from me. And in order to find authenticity about it, it was very important for me to stay in the intimate point of view.

This is a film that could very easily have droned on and on. That doesn’t happen. Your editing is tight; it’s very cohesive in putting all the elements together. Once we get to the climactic revelation, the audience is on the edge of their seats, and yet we still keep sitting on the edge waiting to see what Jeanne and Simon are going to do. I would think that to construct this meticulous emotional apex had to have taken time to construct in editing. How long did it take you to edit?

[The cohesiveness and elements] was constructed in the screenplay and the screenplay was based on the play. All the key elements of the structure were in the play. I knew that the play was a huge success. I experienced it myself. I was in the theatre and I saw how beautiful it was with all the key ingredients in order to let the story work. The play was my Bible all the time. I just tried to keep the equilibrium that was in the play in the screenplay. I’m shooting with not a lot of money. I had to “edit” the film before it was shot. Everything that you see on the screen is almost what I shot. I didn’t have the luxury to shoot scenes just in order to have back-ups. It was just a very precise shooting. So, what I’m talking about is that the editing was not that tough. It was a matter of writing. The structure was almost there. The movie is very close to the screenplay. Some of my previous feature films was almost all improvised on the set and it was all done in the editing room. But, INCENDIES is a very written movie.

Do you prefer working with a very structured written film like this or something that is more improvisional, more free-flowing?

I love both. But I think I would rather work with a precise script and have time to improvise around it. That is the best way to work. One day I will have that luxury; to have a strong screenplay and time to improvise.

And the money to finance it the way you want!

Oh, yes, yes! [Laughing]

What did you find to be the most challenging aspect of filming INCENDIES?

As I said, I think there are two things. First of all, it was to have to learn about Arabic culture. Secondly, was to find the right equilibrium for the dramatic content of the film. Each sequence of this film could be a feature film on its own. There is so much gravity that I was afraid to fail in the middle. I must say “thank you” 10,000 times to my actors because they were so solid. I am very proud of their work. It was a lot of work about equilibrium of the gravity of the story.

Their performances were so nuanced and textured. Simply beautiful. It was very compelling, very riveting, watching the actors on screen and watching this story unfold. Your casting is impeccable.

Which means that I owe them a lot. That’s the thing about this film I am most proud of. Especially the two women. The movie is on their shoulder. I will never say thank you enough to them.

What did you personally take away from this experience?

A lot of things. There’s a lot of cultural difference around the world, but something with families that’s so universal. There’s more things that are close from one culture to another than different. There’s more similarities than differences. What I love about this story is that there is no cynicism. It brought me hope about how to deal with anger inside a family and how to handle violence inside a society. I think for me it was a pure privilege to work on this story. It brought me a lot of hope and joy.

It’s an absolute privilege to get to see INCENDIES because it is so eloquently done. If there was one reason that an audience should go see INCENDIES, what would you say it is?

Boy, that’s a huge question. [Laughing] I’m shy to answer it. I think one of the beauties of cinema is to build a bridge between cultures. Even if my film is a just a teeny bridge, it’s a small one. It’s nice to have another point of view about this part of the world. It’s a nice film to see to have a different point of view about this part of the world. And it says a lot of difficult things about family.

I couldn’t agree more. Denis, thank you so much.

Ah, thank you. You are very generous. It was a real pleasure for me to talk to you because it has been a long time since somebody talked to me about editing or camera movement. It was quite interesting to talk to you. It was my pleasure to talk to you about it.

#