By: debbie lynn elias

When William Lustig’s now classic 1980’s horror film MANIAC first opened in theatres in Center City, Philadelphia, it wasn’t playing at any of the more “respectable” theatres. It was showing in what was once the “XXX” theater area, an area my father always deemed unsafe for me to go to alone. Were he even aware of the nature of MANIAC beyond being “a horror film”, my heading to the theatre to see the film would have only concerned him more as MANIAC is the story of a serial killer named Frank. Dealing with mother issues, Frank was a killer of fascinating proportion, stalking women in the gritty, dirty, “piss-filled” side streets and alleys of New York, killing them, scalping them. Gritty, visceral, raw, MANIAC was one of the ultimate grindhouse “must sees” of the day and has lived long thanks initially to VHS and its compelling box art and then the ease and economy of viewing with mediums like Netflix, VOD, DVD, etc. So it comes as no surprise that MANIAC finally gets a reimagination, this time thanks to director Frank Khalfoun.

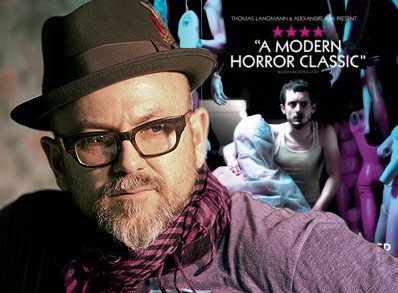

In what is without a doubt as near perfect a reimagination or remake as any film can be, Khalfoun turns MANIAC on its head, literally and figuratively. Shifting the point of view to being completely within the eyeline of Frank, Khalfoun thus immerses each of us into the mind and mind’s eye of a serial killer, forcing us to see and feel what Frank is thinking, seeing and doing. But then he casts Elijah Wood as Frank. No longer a burly hulking menace as Joe Spinell’s Frank is in Lustig’s original, Wood’s diminutive elfin stature belies the evil within, creating an ambiguity that rattles the cages and keeps one on edge the entire film. Interestingly, it wasn’t until years after the film’s theatrical release that Khalfoun was even exposed to MANIAC. Not allowed to see it, “I didn’t even know it existed in theatres. I couldn’t see Saturday Night Fever either. I wasn’t allowed to see [those films] back then.” But once he did, it was forever ingrained in his subconscious fabric.

I had a chance to sit down with Franck Khalfoun and in this exclusive interview, talk about MANIAC, and his desire to not have MANIAC be a “close to perfect remake” but a “close to perfect film.”

One of the really impressive aspects of this film, not that every element isn’t very impressive, is the cinematography. How did you go about designing that cinematography and the overall tonal look because you’ve got this great bluish noir icy feel and then you pop it with color in very judicious moments?

My whole take on the way that this film look was obviously production design and cinematography. I wanted it to look beautiful and then I wanted it to be all drenched in darkness, sort of symbolizing this perhaps beautiful man who is now covered himself in darkness and trying to slowly to reveal himself, trying to come out of that. It just embodies the character. The problem with doing a movie in POV is that I have to use every other element to try and create emotion and create a sensibility. I knew that if I made a very lush, beautiful movie and then darkened it, that it would evoke some sort of feeling, some sort of mystery. You want the veil to be lifted as you want the veil to be lifted on this character as you want to discover, as you hope that this character will sort of lift himself out of this thing. Beyond it being a movie about a man slashing and scalping women, it’s a man looking for love, looking for acceptance, looking for a way out of his wounds of childhood.

MANIAC doesn’t come across as a man slashing. I felt this to be a truly poignant drama about the human condition.

Totally. And I’m glad you feel that way because I think movies are more powerful when they bring something deeper, regardless if it’s a genre film or not, regardless if it’s a horror movie or not. Most of the horror movies that stand time are the ones that go beyond scares and actually tell human story. You can always tell a good horror film if you remove the horror. If you remove the horror and you analyze what the drama, what the life, what the character’s drama is, then you know that you’re pretty much going to have something that stands and that will be entertaining and that will connect. You can’t horrify people if you don’t connect them to your character. If they don’t love your character, what’s the difference. You can’t scare people if you don’t care about who you’re killing.

Scaring here is done with the way you build the tension. You build tension very incrementally so we’re on tenterhooks waiting to see what’s coming but becoming more and more invested in Elijah’s character of Frank, this wounded soul.

You’re right. It’s not your typical sort of fear movie with things jumping out at you. It slowly creeps on you. And the longer you spend in this guy’s mind, I think, the more you want to escape it . . . you’re stuck. In the same way he’s stuck in his brain in doing the things that he does, you’re stuck in watching. You are complicit now. Not only are you stuck as a witness, but you are complicit in what he’s doing. And there’s a strange thing that happens. As you participate, as an audience member you want to see what happens next. But now that you’re complicit in the crime, it has a double edged feeling. You don’t want to leave because you want to see what happens and you don’t want this to happen but it’s happening regardless and you can’t help it. I think that’s what creeps up on you and that’s the sort of difficult thing that there is about watching this movie. I think this beautiful cinematography, this beautiful art direction, this really lush and sort of epic score creates a very false sense of comfort and security. That juxtapositioned with horrific acts of violence, it’s troubling. It’s jolting, I think, in a good way.

Then you also lure us into a false sense of security as the film lightens with the introduction of Anna. You get the porcelain white, white, white, not even a flesh tone mannequin, it’s the porcelain white, white. The purity, the light and you think there’s going to be this great shift with Frank that just pulls you in even deeper.

Yes, yes! It’s funny that you say the light comes in when she appears because that’s exactly [what happens]. The whole movie’s dark until he raises the curtain and there comes the light into his life. There she is in all her radiant beauty and innocence in a way. You’re hoping that this will be the shift for him. That’s why you’re grabbed by him because it is innocent and there is an attraction which works I think so much better than the original in the way that the character has a potential. There’s a real potential here for a relationship and that is terribly dramatic as opposed to the original which you’re just waiting for him to cut her into pieces. Here, you’re hoping, I think , that he changes, that he doesn’t.

You see that humanity that you give him. What led you to cast Elijah? He is perfect, perfect for this take on Frank. Just seeing his eyes or his reflection and not seeing him throughout the movie, but just those mesmerizing eyes of his or his reflection in a mirror or looking in the rear-view mirror, on a glass or window pane – this is not who you would typically think of for a role like this but it adds another dimension and layer to it with his own innocence

He has these beautiful kind eyes. That’s exactly why. It’s the last person you’d expect. I think that’s the most terrifying thing about serial killers – and everybody always says it – “it was our neighbor. We loved this guy. He was quiet, calm. He was nice, polite to everybody, and he turned out to be a monster.” That is so much scarier to me than the guy who looks like [someone] you would run from if you saw him on a street corner. And that’s why initially when producers and everybody started mentioning Elijah, I thought, ‘How interesting.’ So many actors carry this baggage of the past things that they’ve done and I don’t think that’s really the case with Elijah because he has the range, obviously, you can see it in this, that he has the range to do this. But if anybody was going to associate him with past characters, I thought that most of those characters have been good and innocent and I thought, “What a thrill to sort of destroy that mythology. To have him be the catalyst for the story and for these murders. I think it’s terrifying to know that, ‘Wow! If our next door neighbor could do this, then it’s possible for anybody.’”

You’re no stranger to the film industry on both sides of the camera. At this stage of your career, what’s the greatest gift that filmmaking gives to you?

Wow! Ya know, it’s such a hard thing to do. I think that a lot of people think “how glamorous” and it’s certainly not. It’s war. It’s very difficult and I think the state of film and the industry for guys like me and auteurs or filmmakers, it’s becoming harder and harder to get things done. So we spend most of our time churning and hustling and fighting to not only [develop] ideas, but get things off the ground. I think the greatest gift is just doing it, just having the opportunity to do it. For me, the real kick has always been the audience. From when I was directing theater or being on stage, it’s always about that connection with an audience. So when I show a film, I spend my time watching the audience. Always. I’ve seen the film a million times. Even when I did theater, theater was great for that because each performance had its own timing, its own rhythm, its own life, and things would happen on stage. It was magical because it was always different no matter what. So you would end up watching the parade, but you always keep your eyes on the audience as well. For me in the movies it’s how the audience reacts and where I can connect and what I can say and that people actually pay attention. [laughing] It’s so hard to put up congruent ideas and have them stand. With the lives that we lead and the lives that people have, to ask them to sit for 1 ½ hours and watch what you’ve done, that’s the gift. It’s really cool.

#