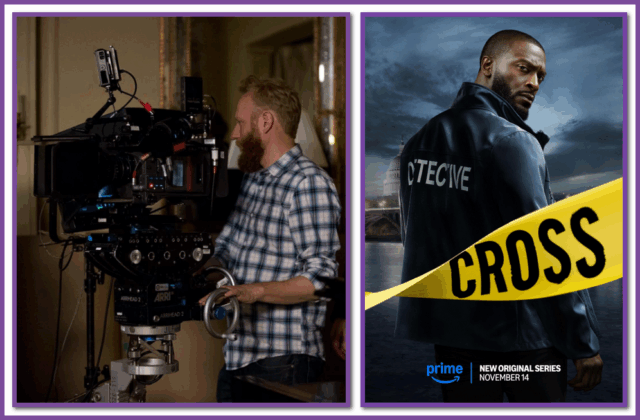

Cinematographer BRENDAN STEACY goes in-depth in this exclusive interview, talking about the cinematographic approach to CROSS, working with multiple directors, establishing visual tone and visual grammar, and more.

SYNOPSIS: CROSS brings James Patterson’s legendary detective Alex Cross to life in a gripping series packed with suspense, action, and psychological depth. Starring Aldis Hodge as the brilliant yet haunted investigator, the show delves into Cross’s mind as he hunts dangerous criminals while battling his own demons. With intense storytelling and a fresh take on the beloved character, CROSS is a must-watch crime thriller. In Season One, CROSS follows Alex Cross, a decorated D.C. homicide detective and forensic psychologist who faces a sadistic serial killer leaving a string of bodies strewn around the city. As Alex and his partner, John Sampson (Isaiah Mustafa), track this killer, a mysterious threat from Cross’ past appears, aiming to destroy what he’s done to keep his grieving family, career, and life together.

Created by Ben Watkins, CROSS stars, among others, Aldis Hodge, Isaiah Mustafa, Ryan Eggold, Alona Tal, Johnny Ray Gill, Eloise Mumford, Juanita Jennings, Jennifer Wigmore, Sharon Taylor, and Karen Robinson.

Light and lens. You can’t have a film or a television show without them. Television and film are moving pictures, and it falls to the cinematographer to capture those moving pictures. BRENDAN STEACY is just one of the talented cinematographers who help create mood and tone, capture action, romance, terror, and in the case of CROSS, a crime thriller that will have you riveted to the screen. I first took note of Brendan’s work more than a decade ago with “The Last Exorcism II” and thereafter watched his range develop with “Backstabbing for Beginners” and series such as “Clarice”, “Rabbit Hole” and “Painkiller”. And now he is the cinematographer for four episodes of Prime Video’s crime thriller CROSS.

No stranger to episodic television, given BRENDAN STEACY’s experience as a cinematographer on the big and small screens, I was curious what attracted him to CROSS. According to Brendan, “I was attracted to CROSS because of the unique vision shared by Ben Watkins and Nzingha Stewart. The two of them that got me excited about it, because they had so much enthusiasm for it and they had such a great sort of vision of what it was going to be that I got really excited about being a part of it…There’s not a single thing that attracts me to anything. It’s always just sort of the right cocktail of things. And this had a lot to do with the fact that they wanted to do something that was a bit different, and that was really in line with what I wanted to do. And I thought there were a lot of just great people involved who I wanted to work with and be part of.” This cocktail of great people and creating a distinctive visual style for the series certainly paid off for not only Brendan but for the series as a whole.

Brendan worked with two different directors on his four episodes: Nzingha Stewart for episodes one and two, and Stacey Muhammed for episodes five and six. Each director required a different approach, but starting with Nzingha for the first two episodes, it was critical to establish the visual grammar. They spent more time establishing the show’s visual language, discussing aspect ratio, and defining the overall look. “We even had identical film references”, which helped to align their vision. With Stacy and episodes five and six, the visual language was already set, so preparation focused on how to accomplish those two specific script needs while maintaining the established style. The key was adapting to each director’s vision while preserving the show’s consistent visual grammar.

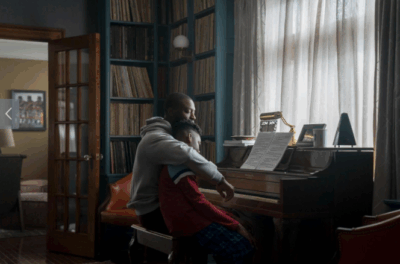

One of the keys to the continuity of the visual grammar was the goal of Brendan and each of his directors to “make sure that we saw the spaces the characters were living in. Like where they were in each moment, geographically and physically, and then also make sure that we gave appropriate moments to connect with them emotionally when we needed to. A lot of the time we wanted to make sure we had a really big wide that really showed a person in their environment… we always tried to shoot something really big so we can see the context of their sort of position in the world in that moment, and where they find themselves. I find that generally, it’s really powerful when you can just get wide enough to really see a person in their space, and then also to sort of see, within the same scene, get close enough to really feel the sort of emotional way to the scene.”

“We shot Alexa 35, which was pretty new at the time and the first sort of long form project I shot on the camera with, like a Summilux. It was a two-camera show, but we had three-camera days whenever we had sort of lots of people, or any sort of action, and either required, sort of an extra lens. We’d grab a third camera for those days. But mostly we worked with it like two camera crews.”

Facing significant practical challenges shooting CROSS on an eight-day episode schedule required moving quickly between locations. On some days, they shot up to four different locations in a single day. To maintain a cinematic look despite the tight timeline, he and his team planned meticulously, carefully preparing locations in advance so they could start shooting immediately upon arrival. “We only moved the camera when motivated by emotional intent or action, keeping shots static when characters were stationary. This approach made our movements feel more deliberate and powerful. We used a fantastic Steadicam operator who could seamlessly transition between moving and static shots. The goal was to maintain a cinematic feel without looking rushed, which required extensive pre-production planning and a disciplined approach to each shot.” They focused on leapfrogging between locations and ensuring everything was ready, all while trying to make the production not look rushed. By carefully planning and maintaining their technical precision, they were able to create a smooth, unhurried visual style that appeared cinematic despite the breakneck pace of production.

Emphasizing the use of “motivated camera movements” as a way to enhance emotional and action scenes, these motivated camera movements are camera movements that have a specific purpose driven by the emotional intent, actions, or narrative context of a scene. As Brendan elaborates, “ I think it was important that the camera wasn’t being, like showy. We sort of made a pretty strict rule that we would only move [the camera] if it was motivated either by the actions or the emotional intent of the scene or the act. If there was an emotional sort of reason that the camera had to move because of what was going on between characters, and then that was okay. Or if we had to follow action, of course, we moved for those reasons. But when people are in a room and people aren’t really moving, but you’re seeing their entire space, we wanted to let it sit and let the people come and go and let the action play out without, without us moving any more than we absolutely had to. This approach ensured that camera movements are deliberate and meaningful, adding depth to the storytelling rather than being purely aesthetic or random.

Establishing the tonal contrast of warm family scenes and the cold, steely police station was done through deliberate visual choices. In the family scenes, Brendan used stationary wide shots that captured the entire space, showing warmth and fluidity of family interactions. When transitioning to the police station, he shifted to a cold, steely gray-green color palette with dimly lit environments. The camera movements became more controlled and purposeful, using Dutch angles and close-ups to create a sense of tension and power. By carefully controlling the visual tone, Steacy created a stark emotional contrast between the loving family moments and the harsh, clinical police investigation, which helps viewers feel the dramatic shift in Alex Cross’s life after his wife’s murder.

Wide shots were deliberately placed. According to Brendan, “I wanted to make sure we showed characters in their full environment and context. Wide shots allowed us to see the characters’ physical position in their space, which helps viewers understand the geographical and emotional landscape of a scene. By using wide shots, we could show the full scope of a location and then move to more intimate, emotionally charged close-ups. The goal was to give viewers a comprehensive sense of the characters’ world while also creating opportunities for emotional connection.”

Breaking down some specific scenes, in episode one, for example, the first scene that jumps out is our first look at the police station and the interrogation scene. It’s very cinematic thanks to the framing and the visual grammar itself, with camera movement and some very beautiful dutching. You can feel the commanding presence of Aldis Hodge as Alex Cross as he goes into the interrogation room and wanders around while the perpetrator squirms uncomfortably at a table. The camera captures the fluidity that Hodge brings to Cross’s movements, and as Cross moves around the room, the camera gradually lowers, creating a visual metaphor of his increasing dominance. “We started with the camera higher, then catching closer, we came down. We wanted to make it feel like he’s getting more and more sort of control of the situation and getting and more powerful defense to take over the dynamic of that scene.”

Another riveting example of Brendan’s handiwork is in episode 5, “What Happened at Ramsey’s”, where there is an intense exchange in a hallway at Ed Ramsey’s house between Cross and Ed Ramsey where Brendan employed progressively tighter lensing, using close-ups in a narrow four-foot wide space to create intense, claustrophobic tension. The overhead shots initially establish the scale of Ramsey’s world, bearing in mind this is our first entre into Ramsey’s home, showing how small people are in comparison to his impressive house, and then the lensing becomes more intimate and confined as the episode progresses, particularly in the hallway confrontation scene. The camera gets extremely close to both characters’ faces, heightening the psychological confrontation between Cross and Ramsey. The key considerations were to use camera movement and framing that motivated the emotional intent of the scene, only moving the camera when absolutely necessary to enhance the dramatic impact and character dynamics.

While the visual tone is intense and claustrophobic in episode 5, focusing on Ed Ramsey’s world and the cat-and-mouse game between him and Cross, in transitioning to episode 6, “A Bang, Not a Whimper”, the cinematography shifts to a more intimate, emotionally connected space during a road trip between Cross and his son. The car scenes are deliberately framed to show Alex and his son getting physically and emotionally closer as they process the death of Cross’ wife Maria. The visual grammar supports the narrative arc of Cross moving from pursuing evil (Ramsey) to reconnecting with love and family, using tight, confined spaces in the car to emphasize their growing bond and shared grief.

At every turn, Brendan Steacy’s lighting and lensing tell a story, define characters, and help to shape the visual tonal bandwidth of the entire series.

This is just part of our conversation about CROSS. To hear more from BRENDAN STEACY about his work and cinematographic philosophies, and CROSS…

TAKE A LISTEN. . .

by debbie elias, exclusive interview 04/02/2025

CROSS is now streaming on Prime Video.