Remember “back in the day” when the arts were celebrated in schools? I do. I was lucky. I went through the Colonial School District in suburban Philadelphia. It was, and still is, a well-funded school district with every program imaginable available to its students. Every school had art, music, a band, an orchestra, not to mention sports. The arts flourished. Instruments were put into your hands as early as third or fourth grade. Some students stayed with the music and their instruments. Others, like myself, did not. But when you realized playing an instrument wasn’t for you, the instrument was turned back in and handed off to another student. Sadly, times changed and not all school districts have funding for basic classroom needs let alone music programs or orchestras and bands. That’s what happened to the Philadelphia School District, and particularly in the low-income area schools. But that begs the question of what happened to all of the musical instruments? In the case of Philadelphia schools, unless somehow dollars could be found for music classes, instruments were abandoned and broken, necessitating repair. Where many may have thrown the broken instruments away, Philadelphia school teachers did not. They stored them, hoping for the day when they could be repaired and put to use again.

So what happened to all those hundreds of broken and unused instruments? Enter Robert Blackson, director of Temple Contemporary at the Tyler School of Art who, together with Pulitzer prize-winning composer David Lang, conceived the idea for Symphony for A Broken Orchestra. Created and commissioned by Temple Contemporary at Temple University the original support for Symphony for a Broken Orchestra was provided by The Pew Center for Arts & Heritage in Philadelphia. But beyond the initial seed funding, money was needed to make all the repairs necessary. Thus the idea was born for Symphony for a Broken Orchestra project which allowed for people to “adopt” the broken instruments so repairs could be made. But before the instruments went off to repair, Lang’s musical composition of the same name was performed in December 2017 by a 400 piece orchestra at the 23rd Street Armory in Philadelphia. The orchestra was comprised of teachers, students as young as elementary school age, amateur and professional musicians, even members of the Philadelphia Orchestra, and each played one of the broken instruments no matter what shape it was in.

It was during this time that documentarian CHARLIE TYRELL learned about Symphony for a Broken Orchestra while trying to find a gift for his sister-in-law, a violin and piano teacher, who lived across the country. Hearing all the buzz about the concert and the project, Charlie adopted a “violin” in her name. And that was the seed that sparked Charlie with the idea to do a short documentary about the Symphony for a Broken Orchestra project called BROKEN ORCHESTRA.

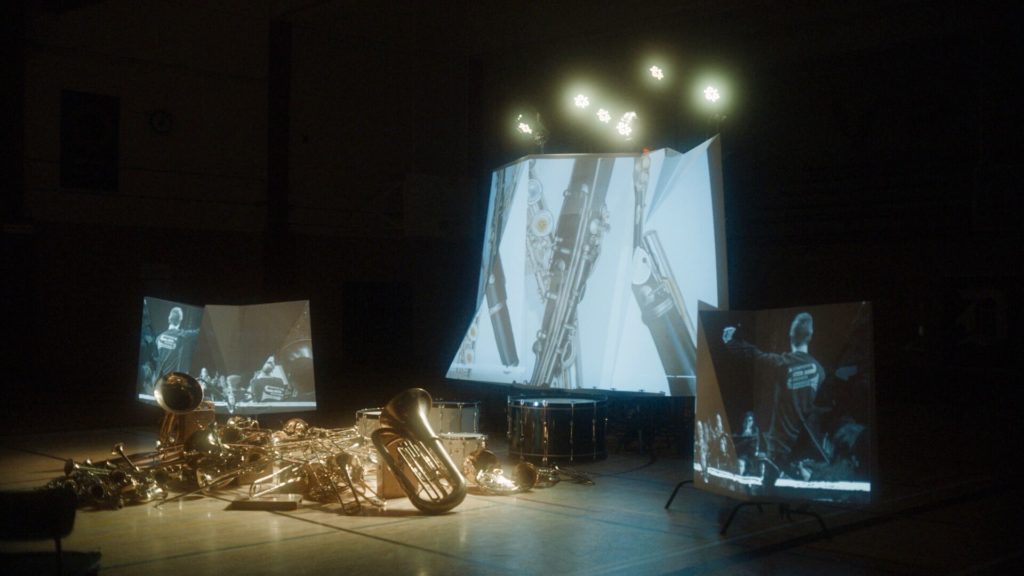

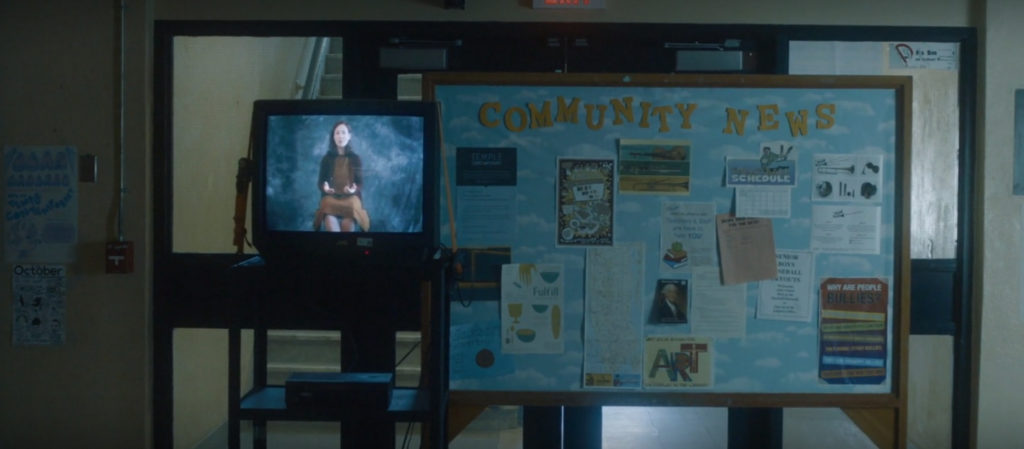

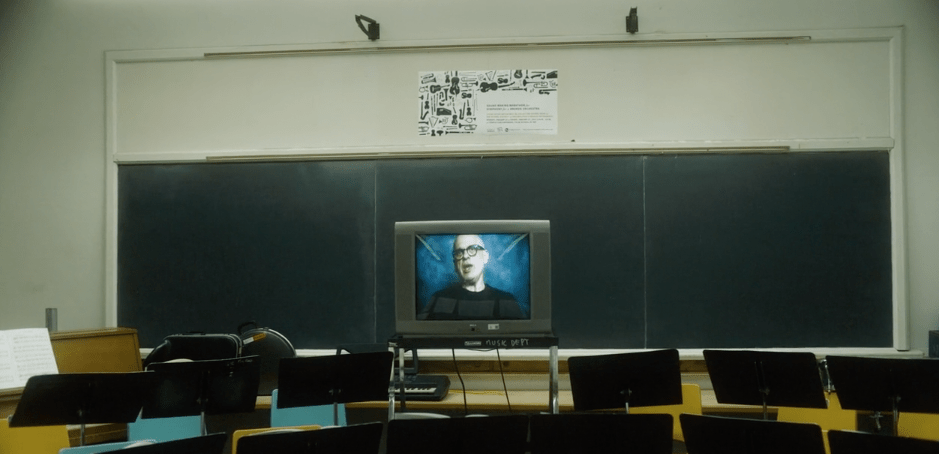

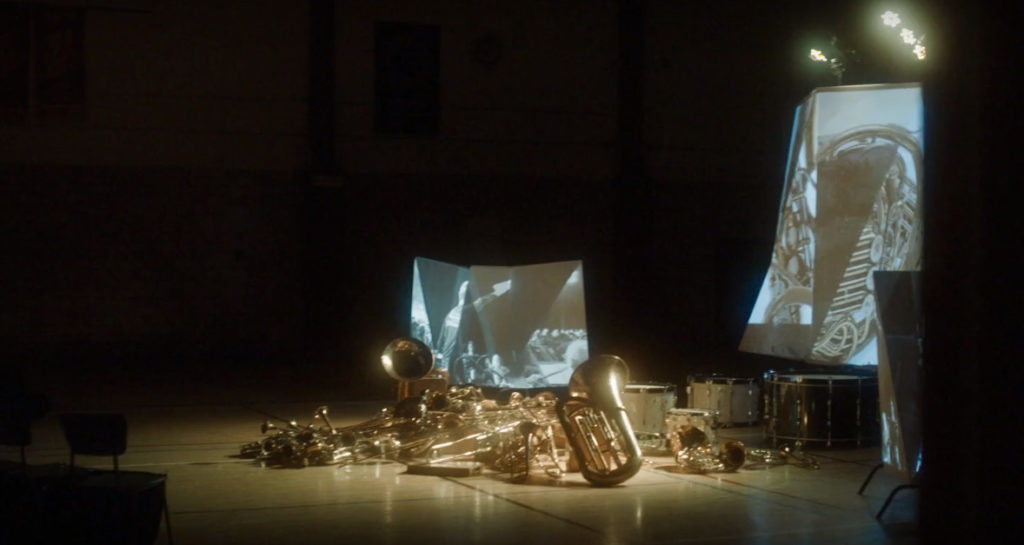

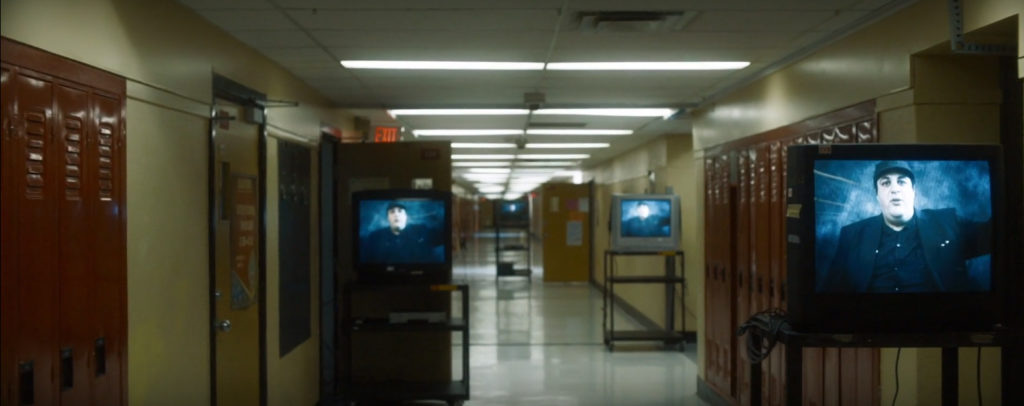

Much like the Symphony for a Broken Orchestra project itself, BROKEN ORCHESTRA is crafted in a very untraditional manner. There’s an old school method to Charlie’s storytelling with old televisions/monitors and wired connections that immediately remind you of when all schools DID have the arts and music as part of the curriculum. Paying attention to sound design, the film showcases the instruments, the sound of the broken instruments, as they come to life, creating a sensory experience. Visually, he intensifies the experience as it becomes more personal for each interview subject as the camera zooms in ever closer on the monitors and the individuals speaking. And talk about interview subjects! We are introduced to some of the innovators, educators, volunteers, advocates, and musicians behind Symphony for a Broken Orchestra. Just listening to each one, it is impossible not to hear their passion for the project. Visual effects and animation are delights that add yet another artistic and creative element to the film. Put it all together and BROKEN ORCHESTRA is as a much an art form as the symphony itself.

I spoke at length with CHARLIE TYRELL about BROKEN ORCHESTRA, its creation, his filmmaking approach, and how a Canadian filmmaker would be the one to shine a light on this incredible project.

I am so enamored with BROKEN ORCHESTRA, Charlie, and as a former Owl, I am thrilled with the entire Symphony for a Broken Orchestra project that Temple has done. This little short is dear to my heart.

It’s an amazing school. I’d obviously never been there before, but it seems like there’s some really great programs, and Temple Contemporary and the way it seems to really support artists and artists in residence, it really blew us away.

And that all came through Tyler School of Art. They truly have embraced the whole idea of public access to the arts and promoting the arts, when they are, as we see here, being so short-funded in the conventional school district system. So, I’m curious, how does a Canadian filmmaker like yourself find out about the Symphony for a Broken Orchestra project?

It’s very fortunate that it got as much press and publicity as it did when it first came out. That’s how I was able to read about it and pick up on it. I know that that’s kind of uneventful. Usually, on a personal level as a documentary filmmaker, I try and find more interesting ways in finding the story or a bit more interesting [in finding one]. But for this one, I just read about it in an article. It was shortly before Christmas. My sister-in-law lives on the other side of the country, and she’s a violin and piano teacher, so it’s usually better to get things that aren’t big packages to be mailed and whatnot, and at the time you could still adopt instruments through the website, so I adopted a violin for her.

I think you can still adopt instruments, yes?

I think you can still make donations, but I believe all the instruments have been spoken for and are recirculated.

I know the plan was to get them all recirculated back in 2018 for the new school semester so that the kids now in school are getting the benefit of using them. So, you adopted this violin for your sister-in-law on the other side of the country. But how did you then approach creating this documentary, which I have to say, I love the untraditional manner that you present this story. You’ve got an old-school method of storytelling using the television monitors, the wired connections. It harkens back to the days when the school districts did have arts and music as part of the curriculum. And they would have TV as part of the curriculum. You really went old school with your approach here, and I love it.

Well, I appreciate that. Going back to your first question, I adopted, and heard the instrument. It went over well. And the story and kind of the idea of this pile of dead instruments just kind of kept sitting with me and sitting with me. It wasn’t long before I figured, “Okay, there’s probably something I could do with that. There’s probably an interesting way to tell that story”; especially considering that the events of the live performance and of the instruments going to repair shops had already happened by that point. I like, as a documentary subject, something that I can look at retroactively, things that have already happened. And with that, you’re not there, you’re not filming things as they’re unfolding. So it kind of mandates needing a different way to tell the story, a less conventional way. I reached out to Robert Blackson at Temple and he was receptive. Symphony for Broken Orchestra was his brainchild, and he was more or less the person that put it all together. There were lots of other people involved and lots of other people that assisted and lent their skills. But the real kind of core idea was his, as far as I understand. So we just started talking. I said, “I’m Charlie Tyrell. I’m a filmmaker from Canada. Here’s some of my work. This is the story I’d love to tell. I don’t know how I would tell it. But if you’re open to that let’s go for it.” And he was on board and it kind of went from there.

In regards to formatting the film and filming in this old empty school and putting TVs on monitors, some of that was kind of initiated by being down in Philadelphia when we were just shooting our interview portion of the film. We were just down there meeting with our subjects, meeting with students, and getting them to tell the story on camera. That was our only real goal of that part of the shoot. But being there and being in these old schools and kind of walking through that kind of environment where I haven’t been in for a long time, it kind of made me remember a lot more about my high school experience that I may have forgotten. I don’t revisit my high school memories very often. I kind of just got in and got out. But we began to realize that if we told this story through the format that we ended up telling it through, that that would allow a viewer to go back into their own memories, their own high school experiences. And with that, the goal is hopefully, they’ll be able to empathize with the story a little bit better because if you’re just watching people talking about Philadelphia and this is what happened and these are the people that cut the budget, then you won’t be able to relate to the problem as well because you’ll just see it as something that’s happening in another city, in another part of the country, or another part of the world. But when you construct it in a more kind of open way, a place that has some holes that you can fill with your own personal story as a viewer, then hopefully that will help people relate.

I cracked up seeing some of your monitors you have sitting on the old AV carts that populated all the schools. And I kept looking at it and it’s like, “Oh my God! They’ve rounded up all these broken instruments. But now what did Charlie do? Go around and round up all the unused old video equipment from the ’60s and ’70s?” I love it! It really mirrors the whole idea of the broken instruments and things being old and needing to be refurbished. So you really carry that through, whether intentionally or subconsciously. It works so well. But something else that you do, on a documentary short like this I am utterly shocked because not too many directors would pay attention to this – your sound! I am in love with the sound design because you slowly start to hear individual instruments come to life as if they’re tuning for the first time, you’re blowing the dirt out of them. You’re wetting the reeds. And then you get to the strings, which are very prominent, tuning just before the concert. Talk about beautifully executed, Charlie! This makes it a fully sensory experience.

Absolutely. I unfortunately can take no credit for the sound in this film, which was basically three parts. And I love working with sound, I love working with music, and I love working with the people that do the sound and music on my films. So yeah, let’s break this down to three parts.

So part one is the actual performance of Symphony for Broken Orchestra. That was a 40-minute recording composed by David Lang, conducted by Jayce Ogren, and performed by around 400 Philadelphia musicians playing the actual broken instruments. So we had to take that piece, and Colin Sigor, my composer, he took the piece, edited it down to our length, chose the moments and parts that worked for the film, and parts that we wanted to feature. And that was kind of step one, cutting it to length.

Step two was for him to add his own flourishes to it, which he did by using this sound recording library provided by Found Sound Nation. And what they did is, once all the instruments were all tallied up at Temple they had musicians come in and play all the broken instruments and record them as little soundbites, anywhere from one second to five seconds, hearing the broken parts. Some instruments that were completely destroyed became percussive instruments. And he created this, like I said, massive sound library. So Colin took that and then pieced together the gaps between David Lang’s score and our moments in the film, and was able to create this one kind of complete piece based off that original score. I always loved working with Colin, and this was a bit of a step back for us because he normally creates his original scores from complete scratch. This was his first time really taking someone else’s work and reworking it and reapplying it. So we’re also happy with his results on there. But yeah. We had some great source material to work with.

The third part is Joe Coupal who is our mix engineer, sound designer, sound editor, that I’ve worked with for a few years now, at least on all my favorite projects I get to work with him. The great thing about Joe is a lot of my films incorporate some element of animation, whether it’s little bits of stop motion or tutto animation. Joe’s day job is basically doing sound effects for cartoons and sound mixing for cartoons. So he’s got this really good kind of arsenal of skills and abilities that lend themselves well to this work. And beyond that, he’s a very talented individual in his field. But for this, he had to create from scratch. I think he said it was the most intense mix he’s ever done because we weren’t recording audio live on the set. We were recording a guide track so then we could sync things later, but you hear myself and our AD talking over the top of the shot, so it was unusable sound. But Joe was able to rebuild it and basically rebuild it so that it sounded like the TVs were playing in the classroom, or in a hallway, or in a big open gymnasium, and really kind of try and make this immersive experience where it sounds like we are walking with the camera and we hear the audio bouncing off the walls in different ways, and moving from space to space. It was maybe one of my favorite things to observe while making this film, just seeing his portion of it come together.

Every element of this, the VFX, the instruments and the chairs in the music room, and then that triptych. That is exquisite. That is beautifully done. That triptych there on the stage before the orchestra is getting ready. You really just bring every element in. And something else you do is with your camera work as you’re going down the hallways and we see that the monitor’s in the distance, and we hear the first voice talking. And it keeps intensifying and you keep bringing us closer and closer to the faces in the monitors. So you’re really building all of this to a visual crescendo yourself. And it just works so well.

That was one of the big challenges with this film. Robert Blackson and everyone else, and everyone involved with Temple Contemporary and the volunteers and the players, they took a problem, they took an issue of instruments in need of repair and how do we find a way to get them back into schools. What I love about Symphony for a Broken Orchestra is they didn’t just kind of say, “Hey, we need money, we need donations,” and go around and campaign. They actually took a problem and turned it into an art piece, which is the composition, which is the piece of music. And then that resulted in the success of the instruments going back and all that. But it’s still a piece of art at the end of the day. So our challenge there was how do we take a problem that was turned into a piece of art into a successful return, and how do we interpret that as our own piece of artwork. I worked with a lot of the same collaborators, and on this film, there’s some new collaborators, like Jesse Yields who did the installation artwork in the gym, and did that projection mapping. Everyone kind of had to do their own piece. Chet and Allen, Allen Kelly our Steadicam operator and Chet Tilokani our director of photography, really finding their own ways to interpret what Symphony for a Broken Orchestra did and how to elevate or channel their specialty to find their own way to enhance the piece of work.

This falls right in line with what the whole function of Temple Contemporary anyway – to reimagine the social functioning of art through its social relevance and significance, on a local and a global level. And I really think that you have met that challenge and have met the Temple Contemporary’s mission statement with what you have put together for BROKEN ORCHESTRA.

Well, thank you so much for saying that.

What is it Charlie that you look for when you’re going to tell a story? I look at the things that you’ve done and it’s all very eclectic, very diverse. So I’m curious, what is it that speaks to you? Do you look for something in particular before you sit down to do a project? Do you have goals in mind or ideas of stories you want to tell or showcase? I’m curious because this is so out of the blue.

I kind of think of it like a big kind of pie chart and the values would be sliced kind of varying, depending on the project. And it is adaptable. One piece is, do I empathize with this story, is there an emotional reaction that I get to the story? Whether it’s a narrative that I’m thinking of, or I feel like I need to tell, or a documentary subject that I’m thinking I need to tell. The other portion is kind of, is there something interesting I can do with this story be it visually or something else? Is it something that should be, you know a Steadicam walkthrough the school, should this be entirely animated, in stop motion? Or should this just be kind of me and the camera and the team and actors? Should it be more kind of raw and conventional in that sense? And then the last kind of little slice is just, it’s basically impulse. It’s am I inspired by this and am I driven to do it? And that kind of takes control of the whole project because if it’s not there then it’s not going to be work that I may consider to add value to my overall kind of body of work, my whole kind of portfolio if you want to call it.

So what did you take away from this particular project? What did you learn about yourself as a filmmaker, as a director, in bringing this story to life?

Oh man! So much. I’ve never been as inspired while making a film, I don’t think. Usually, from the start to finish of making a film I have a fairly good idea of what I want it to be and what I want it to say, and how I feel about the story already. My feeling of the story doesn’t really change that much from the start of making the film to the end. But this one, it changed so much and not really in a change of opinion or view, but just I became more invested in the story as we worked on. And a lot of that I attribute to our interview subjects and the people involved with Symphony for a Broken Orchestra. These were people that were so dedicated to this arrangement, to this project. And not only that, but very insightful about it, very articulate about it. They didn’t take its meaning superficially. It’s something that some of them have gone on to dedicate their life to now. Some of them have changed careers to try and continue Symphony for a Broken Orchestra nationally and into other cities and other schools. So that was pretty contagious. It turned on a few switches in my brain that maybe weren’t on before. It’s made me more conscious of trying to involve myself in my community through my artwork and through other people’s artwork. And trying to find ways to find art and find creativity, find a way to relate with others, that I may not necessarily have done before.

by debbie elias, exclusive interview 06/05/2019