BEN SMITHARD quickly became a favorite cinematographer thanks to “The Trip”. His work in films like “My Week With Marilyn” and “The Second Best Exotic Marigold Hotel” just solidified my respect and admiration for his work. Ben has a keen cinematic eye for visual storytelling that shone brightly with the period piece “Belle” and then soared to emotional heights with “Goodbye Christopher Robin.” He understands light. He understands the power of the lens and framing of a shot so as to create a specific emotional experience for the moviegoer. Calling on his prior period piece work in both film and television, despite being a “newbie” to the world of DOWNTON ABBEY, Ben Smithard comes on board as cinematographer and camera operator and delivers one of the most beauteous and majestic films of the year.

But before delving into “Downton”, we took a trip down memory lane with “Goodbye Christopher Robin”, a film with “not a big budget” and a period piece filled with emotionality and lensed in the same geographic region as DOWNTON ABBEY. As we saw with “Christopher Robin”, Smithard is gifted with the use of negative space and melding that with color correction, two elements that are showcased in “Downton”, most notably when downstairs in the heart of the manor with the staff. Another element that fuels Smithard’s talents is location and the authenticity of the environs. With “Christopher Robin”, one of the biggest touchstones for moviegoers and the film crew alike came with the scene “Pooh Sticks.” Wistfully reminiscing, Ben recalled, “We ended up using the real Pooh bridge. Obviously they’ve changed it a little bit, but it was in the real location where they did that. That was his same stream, the same little river, because the house that they lived in was just up the road from the bridge. We couldn’t shoot in there because it had been modernized, so we had to shoot in a different location for that. But, we shot at the real place that they did the Pooh sticks, the real bridge.” Other elements of that film may not have been shot in the exact location where they occurred oh so many years ago with the real Christopher Robin Milne and Pooh, but when shooting in and around London, other suitable locations are available. “The forest is a different forest because the real place wasn’t so great. But I found this forest which is at Windsor Great Park, just south of Windsor Castle. It’s the most beautiful amazing forest you’ve ever seen in your life. When I found it, I said to Simon [Curtis], ‘We have to shoot here.’ Simon kind of really wanted to shoot where the real 100 Acre Wood was, but it wasn’t really a 100 Acre Wood; it was just a kind of forest at the back of their garden. But I said, ‘Look ! This place is beautiful.” Nobody goes there and it’s this secret place almost. It was just beautiful. It was just amazing. That’s where most of the footage is.”

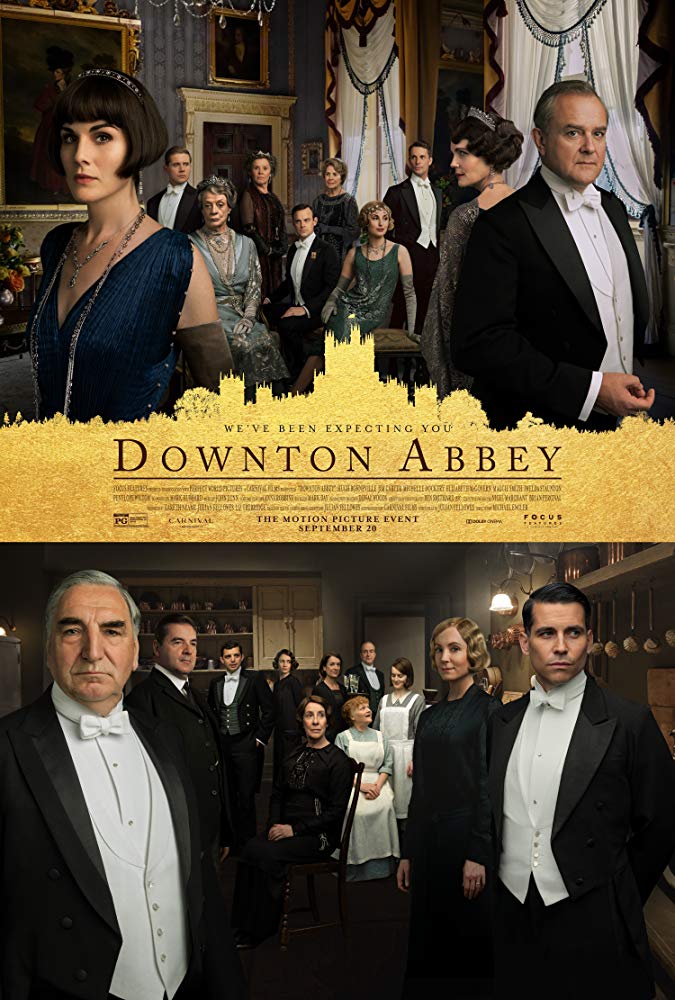

It’s that same spirit and vision which BEN SMITHARD brings to DOWNTON ABBEY as he takes us deep into the world of the idiosyncratic Crawley family as they ready for a visit from the King and Queen of England. Directed by Michael Engler with script by Julian Fellowes and production design by Donal Woods, the beloved cast from the television series returns led by Dame Maggie Smith, someone whom, along with several other cast members, Smithard has lensed in the past. Set in the early twentieth century just as the world is about to change forever, and the ideals of a monied aristocracy and the monarchy shifting, the visuals and accompanying emotional tonal bandwidth are essential to capturing the setting sun of this beloved and jaw-dropping lifestyle and its inhabitants.

I spoke at length with BEN SMITHARD about DOWNTON ABBEY, the challenges he faced shooting in historic locations, his selection of cameras and a blend of Zeiss, Angeniuex, and rehoused vintage Lumiere lenses, using balloons and drones, capturing that elusive light that speaks volumes as to time and place, and the pure joy of shooting DOWNTON ABBEY. Not only the cinematographer, Smithard is one of the rare breed that serves as his own camera operator adding yet another layer to the film’s visual excellence.

I must confess, Ben, that I never watched the show, not even a full episode. But then I saw the film and with the opening aerial shot, you drew me right into this film. Then, as we keep going and going, my jaw kept dropping with the beauty of your lensing and what you were doing. It made me go back and watch the series episodes. How you were able to somehow make this television series expand into cinematic grandeur is beyond me because the television series itself was pretty darn grand. So cinematic. And the grandeur! Grandeur is the word. Every moment of this film you feel the grandeur of this waning time, the fading of the aristocracy. It comes down to your lensing at capturing this and conveying that.

Perfect. I appreciate the kind words. There’s a lot of work that has gone into it. I’ve never shot a movie based on a television series before, so it does help you a little bit, it having been done before. On quite a few of the episodes they did a really good job and it did look really nice, so there’s a little bit of pressure on me to make it look even more amazing. But, I had really good producers. I had a really good director. I had a great team behind me, and the production designer I know. With the production designer [Donal Woods], I did “My Week With Marilyn” with, and the tv series “Cranford”, so I’ve known him for 12 years, and he did all the ‘Downton” TV series, so having a really strong ally in the production design is a really big thing. Producers just gave me a really good brief. They said, “Just make it as epic and as big, and as cinematic as you possibly could.” So, as soon as they said that, I was off to the races. Also, I had worked with the producers, I had worked with Gareth Neame and Liz Trubridge before, so I knew them, and they would just be really supportive. They were just brilliant producers and just really helpful all the way through the process. They saw what I was doing and they respected what I was doing. They understood where I was coming from all the way through. Within the scale of the budget and the schedule, or whatever, what I could do was just be as expansive and be as interesting with the way that I was shooting as I possibly could. I had a lot of work to get to the point where I get what I needed, but that’s normal. I’ve shot a lot of pallid feature films before, and I love doing them.

There’s a lot of things in “Downton” I’m really proud of. I must admit, it was one of the greatest experiences I’ve had of shooting a feature film because I just really enjoyed from the beginning to the end. The whole crew were great. The costume design and the makeup designer, the production designer, they were all great. It really helps because you need that. Films are hard work. They’re just relentless. There’d be times when I was at Highclere, staying around the corner, and I’d get up at 4:00 in the morning because I wanted to get a little bit of mist over the castle. Some of those shots didn’t end up in the final movie, but I still did it. Some of those shots, the drone shots, the helicopter shots of Highclere Castle, are done pretty early in the morning when it would just be me and a few other camera crew, and we’d do it before the filming actually really started because I wanted to get this perfect light. I knew I had this five-minute window when it would be absolutely perfect. It was just enjoyable. I just loved it from the beginning. The cast was great. I had worked with a lot of them before. I had worked with Maggie Smith on the “Marigold Hotel”. I’d worked with Michelle Dockery on “Henry IV”. Some of the downstairs cast I didn’t know, but they were great. Filmmaking is always hard, but once you’ve got a really good crew and the cast is all great, it was just a joy. I really wasn’t expecting it to be that enjoyable to shoot, but it really was. It really was.

You mentioned the lighting and capturing the right light. Number one, we have that autumnal light. Light is very specific in England. And you mentioned the mist. Because it is an island, it’s a whole different texture to the air, unlike if you’re shooting in the United States, or if you’re down in the desert. Everything has a very specific look, and the light diffuses in place with that, specifically. But, you carry that natural light of outside and you bring it inside. I’m very curious about the interior lighting because you’re dealing with Wentworth Woodhouse. You’ve got Highclere House. You’ve got Harewood House. These are historic places that are centuries old. You’ve got antiques, paintings, tapestries. There’s a reason light doesn’t get into these places because light will destroy these artifacts. So I’m curious how you approached lighting for the interiors. Were you limited in light kits you could bring in, what you could use? And then, just navigating around historical pieces in there because you can’t drill holes into the walls. The logistics of that for you as a cinematographer had to be daunting, I would think.

Well, it is and it isn’t. It’s a really good question. It’s a really good point. I’ve spent a lot of my professional career in big houses and castles like this, so I know what they’re like. The hardest thing is not the daytime, because the daytime, most of the time at least, you can light through the windows. I always try to make things look as natural as I possibly can. There’s a lot of big spaces, especially at Highclere, but also actually all of them, even the house that we saw in the sequence with the Queen and Imelda Staunton’s character when she goes to meet the Queen at the beginning, that’s another big house. It’s all lit from outside because the hardest thing is actually the interiors at night because you have to close the curtains, and you literally cannot touch anything. Sometimes the furniture they’ve got in those [houses] is so expensive that you literally can’t move it. So it’s not only difficult to light, it’s difficult to move around the place. But I’m used to that so I know when I go in there that I’ve got very few angles with which to light the interior location, as it is not meant for light. But you have to be well planned out.

Highclere is tricky, but the people there are really helpful because they’ve had the TV series there such a long time. But, you can’t touch the walls. You can’t touch the ceilings. In the dining room at Highclere in the film, at night it’s really tricky because you have these practical shades, these table lamps and standard lamps, and various sorts of things. At least they had electric lights, so it wasn’t all candlelit. There were candles on the table, but they don’t really give enough light for you to shoot with. So, you have to float balloons. But even balloons, which are very lightweight, they still can’t touch the ceiling, so you have to have little guide ropes on them, and then those guide ropes get into the shot if you’re not careful. You can’t let it float to the ceiling because they won’t let you do that. There’s all these problems, but it’s not as though these are problems I don’t know about because I’ve been through them in similar situations and similar houses before, stately homes, so I know what I’m going into. So, you just have to be really well-prepared. It is tricky because, for example, the bedroom sets aren’t done on location. They’re done in the studio so they’re much easier because I can hang lamps from the ceilings. I can screw into the ceiling. I can do whatever I need to do. I still have to be respectful of the set because the set’s beautifully designed and beautifully decorated, but at least I have this ceiling in a studio, which I could do things with. It’s the same for all set pieces. As soon as you go into a studio, you have this freedom. But sometimes the restrictions of the location force you to be simpler with the light and that kind of works. The scene between Maggie [Smith] and Michelle [Dockery] towards the end between Mary and Violet, there was only one place in the room where I could put a light, so what I had to do was manipulate the two of them to be sitting down in the place that I wanted them to sit down, and then I could light them from there. But trust me, I couldn’t touch a thing in that room. The people who looked after the house, the National Trust, there’s two of them in the room with you when you’re shooting, which is difficult, but trust me, they won’t let you go anywhere near anything. You can turn the table lamps on, and turn them off, but that’s about it. You can’t move a few stones. You can’t touch the walls or the ceiling, so there was only one place I could put the light in that entire room, so I had to make sure I got both Michelle and Maggie in the place I needed, otherwise it just wouldn’t have worked. But that’s normal for me, to be honest. It’s hard work, but I love doing historical films, so I have to put up with it.

That’s why you were the man for this job, Ben!

Well, I hope they thought so. I think the producers were all very happy. It was a great film. It wasn’t a big Hollywood mass production at all, but I just tried to put every single penny or cent on the screen, I really did. I operated the camera on every single shot. We didn’t have second units. The only time we didn’t operate the camera is when the drone shot around the castle. The early aerial footage of the train was all done, of course, with a helicopter because it wouldn’t have worked with the drone. But 99.9% of the film, I operated the camera and lit it. It’s a labor of love. The studio spends a lot of money on these things, so it behooves me to really concentrate on every little moment. And also, you’re completely right about the English weather. Most of the time, because it’s got a little bit of overcast, it has this soft overcast light, which can be really useful, actually. But then in the autumn here, which I think is the best two or three months to shoot in this country, the light changes more drastically and quicker, so I can go from a storm to beautiful sunlight to overcast in the space of half a day. You need a bit of luck, but you need to really plan it out that you know you’re shooting your exteriors when you want to. There were a couple of locations where we reshot scenes, which is the real difference between a movie and a TV series. With a movie, you have enough time to do that on the odd occasion when the weather just wasn’t right. I just said, “Look, we need to do this again.” And everybody understood. There was one occasion, I think it’s where Isobel and Edith walk out to the house towards this Victorian cottage. She’s talking to her husband, Bertie. We were supposed to do that in the morning and what happened was it was foggy in the morning. I just said, “You know what? We can’t shoot this because it just won’t work with the rest of the scenes.” So I put my foot down. I didn’t really know what the reaction was going to be. And we went inside and shot some of the inside, came out later in the day to shoot, and I could’ve ended up with a lot of egg on my face but you know what? The light was beautiful. It’s what you see in the movie. It was beautiful. God was looking down on me. But that’s just hard, and sometimes you’ve got to make decisions that could cost the production a lot of money, so that puts you under a lot of pressure. I really believed in the film. We were getting great footage so I just went, “You know what? We can’t shoot this. Let’s just come back, do it again later on.” It had to be better than it was because we couldn’t see anything. The house was surrounded by fog, but those were the shots that we got in the end. But it was just a joy.

I’m curious, Ben. Obviously you’ve got some cranes happening inside the interiors at Wentworth during, I think, the ballroom scene you were using crane. And you’ve got some beautiful dolly tracking shots happening. I’m not picking up any handheld. Did you do any handheld shooting on this one?

The ballroom was a crane. Yeah. Handheld, not really, no. Hardly any. That’s another interesting question. You’re full of interesting questions. We were going to do handheld for a lot of the downstairs footage in the kitchen and the service hall, but when we got down there, because I spoke with Liz Trubridge the producer about this – I know Liz very well and we get off really well. She’s a fantastic producer – I discussed this with Liz and she was very happy for me to do it, so I think that coming from a producer, that’s a good thing. But when we actually got down to the downstairs, it didn’t really work. I didn’t feel it necessary to differentiate between the upstairs part of the house to the downstairs part of the house with handheld work because there’s such a big difference between upstairs. Upstairs was just this very lush, very rich, very multicolored space. The library is very red. The study is very gold. The drawing room, which is only for one scene actually, it has this very beautiful green wallpaper, and the dining room is a different color. It’s what you expect from a very wealthy family, stately home in the early 20th century. Then downstairs, it’s all the same color, the paintwork, it’s all the same color because for obvious reasons. They’ve obviously painted it. In reality, they would’ve painted it, but they didn’t give it lots of different colors because they weren’t interested in making their staff feel better. It didn’t dawn on them that maybe that might help make the staff feel better, so it’s all the same tone. The differentiation between upstairs and downstairs is already made because downstairs is all built on the stage.

All upstairs is all real in Highclere, the dining room, the drawing room, and the great hall, or whatever. But all the downstairs is built on a stage, so I could also use smoke as well. All the downstairs has a little hint of haze in the air, so that helped a bit. The lighting is a little bit different. It’s a little bit gloomier. There’s no natural light. Even during the daytime, the windows are very small and they’re quite high up so the lighting was slightly different in the downstairs. So when we got down to do it, I didn’t feel it necessary to do handheld work because – and this is the key thing – a lot of time, even downstairs, you’ve got a lot of people in each shot because there’s a lot of stuff, and then the King and Queen come, and then there’s all of the entourage. They come down. So sometimes, there’s a lot of people in every scene so I didn’t feel it necessary to have this camera that was kind of not steady. I think it would’ve taken your eye away from what was going on because there’s so much going on in every scene. So there’s hardly any handheld. The only handheld I definitely remember was the scene in the club with the butler who goes to this nightclub. That was all handheld and some of the footage outside. That was the only scene that was predominantly handheld. The rest of it’s on dollies, or cranes, or just quite solid filmmaking because it just suited the story. I didn’t want to suddenly go into like a really strong handheld feeling on the film because I just think it would’ve distracted it. It was unnecessary.

There’s enough activity going on downstairs at all times, and there’s enough eye candy around with the kitchen accouterment that I think a handheld, with movement on top of continual movement, I think you made the right call.

Thank you very much. As I said, we were planning on doing a lot more handheld downstairs, and we just didn’t do it in the end because sometimes you make those calls when you get it. It slightly depends on the very first thing you shoot downstairs, and then you just go with it, and this feels better. You can change things. None of the film was storyboarded at all. We didn’t storyboard any of it but for, of course, the scene in the street with the horses. But by the time we actually got to shoot it, we didn’t really use those storyboards. With these kinds of films, I always feel the whole film is in my head before I start shooting, so I didn’t feel as though I needed to [storyboard]. To be honest, I’ve shot only 12 feature films, and I haven’t storyboarded any of them because I can visualize what the story should look like.

Having said that, then I’m curious how you visualized the beautiful ballroom sequence because the camera has a lyricism to it. There’s a flow and it’s so beautiful. You’ve got the crane shots coming in, and it’s gorgeous.

You know what helps? Some of it helps that you’ve got music playing because then you can feel the mood. The actors were obviously dancers. I loved the choreographer. She was wonderful. She was just great. So we had rehearsal. They knew what they were doing. Some were better than others. Most of them were really good. But as you’d expect, they’re not dancers. They’re actors. I just feel the music. I saw a lot of music videos when I first started in my career. I just feel the music. Some said if you’ve got a good choreographer next to you they understand what you’re trying to do with the camera. I was just trying to float with them because it’s a moment in their lives. It’s a relief, I think, because it’s the end of this big meditation from the King and Queen. A lot of the story’s getting resolved. Actually the scene with Branson and Lucy, which is outside, the exterior dance, so they’re dancing together, that wasn’t in the script at all and it wasn’t planned. But again, it was one of those things. I was with Liz [Trubridge], the producer, and she was interested in doing it, but it wasn’t scheduled. It wasn’t scheduled at all. It wasn’t in the script, and I said, “Let’s just go for it.” It didn’t take very long to shoot and I said, “Liz, let’s just do it. Let’s just go for it. We don’t know whether it will fit in with the film, but. . .” Luckily the light was just beautiful. I just got the Steadicam. I just got to float with the characters. There wasn’t any music then because we didn’t have a band playing, or whatever, but I said, “Just feel the music.” Obviously, I didn’t operate the Steadicam but I just said to the Steadicam operator, “Just feel them dancing.” It’s a moment of them being on their own because those two characters could never have gone with the rest of them in the ballroom. That just wouldn’t have been allowed. It just wouldn’t have worked unless this story was slightly different. So that was kind of an improvised moment that we did. We shot it in like 10-15 minutes and it was just beautiful. If you look really carefully as the camera swings around, the moon is in the background and you can quite clearly see the moon. That’s just a bit of luck that you have, and a bit of foresight, but having a really good producer like Liz Trubridge with you is amazing because she goes, “You know what, Ben? Just go for it.” It was great. I love doing stuff like that.

I’ve got to ask you about your technical choices of cameras and lenses. You went with a Sony Venice 6k for this one. I’m curious as to your thoughts on going with the Venice, but also your Zeiss Primes and your Cinema Zoom that you used. Number one, I’m a huge fan of Zeiss. Cooke and Zeiss, I love them. The Zeiss Primes, I know they work really well in low light, but there are other lenses. Cooke has some that do well in low light. Angenieux, I don’t think they do that well. But I’m curious as to why you went with the Venice camera, and then the Zeiss lenses you chose.

Well, the Venice had only just come out and it’s obviously a very high-end camera, Sony. I’d heard about the camera. I’d shot two films, “Belle”, and “The Second Best Exotic Marigold Hotel.” I shot both those films on the last high-end Sony camera, so I knew they were really good, but I had to test the Venice to make sure it would give me what I needed. Obviously, Sony has managed to do things a lot of other camera companies haven’t been able to, redesigned, in a sense, the camera from the bottom up. They’ve got things in the camera that a lot of other camera manufacturers haven’t managed to do. I knew it was going to be reliable, but the thing is, because the sensors are a little bit bigger, none of the lenses that we normally use would cover that size sensor, so we had to find lenses that could cover that. Some of the lens manufacturers have designed them, and Zeiss designs the lenses called Zeiss Supreme, so we tested those. I thought they were going to be a bit too sharp and bit too clinical. I loved those lenses, but I worried that they weren’t right. But I kept them and tested them. To be honest, I didn’t have a huge amount of options because there weren’t that many lenses around on the market, so I had to go with them. Actually, they worked really well. I used Angenieux Zooms because Angenieux are the only people that really make zooms that I know of that I’ve worked with before. I know that there are other manufacturers, but their zooms are pretty good. We had to mix and match it a little bit. I also shot some of the scenes on these vintage Lumiere lenses that I’ve had. They were stills lenses, and they were designed for medium format cameras, so they worked with the larger sensor. There’s a few scenes in the film that we shot with these Lumiere lenses and I still own them to this day because I got them all rehoused so they would work on a movie camera. They were beautiful. They were amazing. I didn’t have enough of them to cover two or three cameras, so I couldn’t use them all the time. I only used them on a few scenes, but they were beautiful. The scene with the Queen and Imelda Staunton is shot on those lenses. If you ever get to see that scene again, it looks pretty amazing. It’s set back in the interior back in the palace. It’s beautiful. Those lenses are amazing, but I couldn’t really shoot much of the film on them, so I thought most of it on the Zeiss lenses.

Wow! Now with the lenses that you used, do you implement any filters in there? Or do you shoot them straight?

Yeah, you have to use little bit of filtration. It helps with the lenses. It helps with the sharpness of the digital image to not make it so sharp. In an eye-filled perfect world, I would’ve shot the movie on film, on celluloid, but it becomes difficult so I didn’t do that. So you need to help the image along. When we created the film, I thought this eye standard looked great, but I did use diffusion in certain areas because it does help out. But, you have to be careful it doesn’t get over-diffused. If you’re not careful, it’ll end up looking like Dallas. It needs to be subtle so you don’t really notice it. In a lot of scenes that we used diffusion, sometimes it’s just very, very thin diffusion, not very heavy. Sometimes you can almost put a piece of glass in the front of your lens just to make it less sharp, so everything’s quite subtle, to be honest.

We did do a 4K Dolby cinema-grade of the film which can obviously only be shown in certain cinemas because there are only 200 Dolby cinemas in the world, I think. But that looks really amazing. That will blow your mind. I’m pretty sure that a couple of cinemas in Los Angeles that are Dolby cinemas. We spent a week doing that. When you see it in 4K Dolby cinema production, it’s just stunning. It’s a different experience because a Dolby cinema is all pure black inside. There’s no ambient light at all and there’s so much more detail in the images that it will literally blow your mind. It’s like, “Wow!” It will feel as though you’re really right in there in every single scene. The technology of Dolby cinema is just phenomenal. It blew me away. I’ve never done a film in Dolby cinema. I did some in Dolby HDR for domestic televisions, but I’d never seen anything in Dolby cinema, and it’s just unbelievable.

How many cameras were you shooting on this one, Ben?

We shot two cameras nearly all the time, and then sometimes three, and sometimes four. But the four cameras were only on the parade sequence, and the dining room sequence was with three cameras because the dining room sequence is like a black hole of time. We’ve all done big dining room scenes before in period films, however, you’d think I was able to get it to do this, and this is going to work, but they still just suck up time. They just take forever because at the end of every tape the food has to be changed. However clever you think you’re being, they still take ages. So every time we do a dining room scene in DOWNTON on the film, it would always be a day, a whole day just to do the scene. Whatever happened, you couldn’t do it in less than a day. It was impossible. The detail on the work is just over the top. Also, we had these historical advisors who were just great. They knew everything. I think most of them are ex-military, so very close to the Royal Family because they’re all connected to the real modern-day royal family. They literally know everything, these historical advisors. Alistair Bruce is the main one and he was really helpful, really, really helpful, and a real gentleman. I couldn’t get it wrong.

I want to ask you Ben, before I let you go today, I’m curious about the parade sequence with the Yorkshire Hussars calvary, with all the horses. Kids and animals. The bane of filmmaking. You don’t have kids in this film, but you’ve got animals here. 100 horses in formation in a parade outside. Did that present any kind of challenge? Was the weather cooperative for you, at least?

Thank you. You’ve come up with some great questions. You really have. The weather was very cooperative. It was a big sequence because we had to close down pretty much the whole village; definitely the whole street where the horses moved down. But yes, there was 100 horses. It was organized very, very precise detail. I chose that location. They came up with another location, and I said, “You know what? It’s not going to work. Why don’t we shoot in Lacock?” which is this village in Wiltshire in England. We had shot there for “Cranford”, which was a BBC TV series about 10 years before. Donal and I knew it. It was a big scene we shot over, I think, three days. It cost a lot of money. You couldn’t go back and reshoot if you didn’t get what you wanted, so there was this huge amount of pressure doing that scene, there really was. The horses were great because they were marshaled by the real military, so they were great, but obviously they need to be looked after. There was this huge job at the back end of production just to look after all these horses, and feed them, and water them because they were there for three days. I love doing those big things. I really do. But you know what? Nothing went wrong. Nothing went wrong! We were so lucky. The weather was great. We were really well-organized. And we got everything we needed. We were pretty tight towards the end. We didn’t reshoot anything at all. It was tough. The weather was amazing. It was at this time last year, actually. B ut yeah, it was a pretty big sequence. A lot of things could’ve happened if it had rained or the horses got sick, or whatever. I think one horse did trip up or slipped on the tarmac or the concrete, but I was operating a camera on that and I didn’t see it because all the other horses just carried on and it was out of my view. I think it was okay. It didn’t hurt itself, I don’t think. But yeah, a lot of things could’ve gone wrong. You should’ve seen the face of the co-producer, the main guy who organizes the whole shoot, Mark Hubbard, you should’ve seen his face at the end of the three-day shoot because he was so relieved. He was in charge of the finance of the film, in the sense of how he organizes the schedule and the budget, and stuff for that, so he was so relieved.

Will we see you throw your hat in the ring to do a DOWNTON sequel? There’s already talk all over the internet now that Julian [Fellowes] has been told put pen to paper and start coming up with something because they’re just so happy with the theatrical reception.

If they ask me, I’d start tomorrow. I would because I loved everybody who made it. I mean, everybody. Gareth Neame, Liz Trubridge, are truly amazing producers. Of course, I would. I would just say, “When would you like me to start?” We spent three weeks at Highclere. I stayed in a little pub just around the corner from the house, so it took me two minutes to drive to the castle every morning. You’re there at 6:00 in the morning, just looking at this house, and it’s a beautiful house. I was quite blown away when I first saw it. I didn’t do any of the TV series, but it’s a pretty special place. The estate is amazing. There are lots of houses like this, stately homes in England. It’s just what we’re known for, but not many of them as quite as special as Highclere. It’s actually really beautifully designed, and it has a great atmosphere. It’s only about an hour and a half outside London. You should come see it. It’s not far from Stonehenge, so do Highclere Castle and Stonehenge all in the same day. You can do Lacock, which is another hour further west, which is a village. It’s a beautiful village. You could do that all in a day. You’d have the most amazing day. You really would. It’s been great talking to you. I’ve done quite a few interviews but your questions were really interesting, I thought, really interesting. You had a different kind of view on it than quite a few people, which was really good. It was very interesting and I appreciate that a lot.

by debbie elias, exclusive interview 10/10/2019