Music is always an important element for any film be it with score or needle drops. But it is even more crucial when the film lacks dialogue and relies on the score to serve as the communicative and connective tissue among the characters on screen as well as with the audience. Just think of a silent film and how important music is to creating and conveying the emotion of the story and characters. Anyone who has been to a Turner Classic Movies Classic Film Festival understands this tenfold if they attended one of the silent film screenings with live orchestral accompaniments. And then we have the creative minds of Nick Park and the folks at Aardman who first introduced us to the world of Shaun the Sheep back in 2007 with a 7-minute short which has since blossomed into multiple series and feature films, the latest big-screen adventure being SHAUN THE SHEEP: FARMAGEDDON.

For those unfamiliar, Shaun the Sheep began as a stop-motion animated series starring Shaun as leader of his flock on the Mossy Bottom Farm where he would get into the wildest and most madcap of adventures with his fellow barnyard friends ala The Keystone Cops. Over the years, Shaun has blossomed into a global franchise spanning multiple television series and specials, films, video games, live theatre, and even a theme park in Sweden. And the one consistency within it all is that there is no dialogue. Communication in every iteration of Shaun and company is reliant on a perfect marriage of the animated visuals and the score. And that’s where composer TOM HOWE comes in.

Already a rabid fan of Howe’s work thanks to indie gems like Is That A Gun In Your Pocket and Lost and Found and quickly followed by the animated films Charming and Early Man, I was anxious to hear what he would do with his first foray into the well-established Shaun the Sheep franchise. Needless to say, I was not disappointed. With over 70 Emmy and BAFTA-winning dramas and documentaries to his credit, including Professor Marsden & The Wonder Woman, Whiskey Cavalier, Wonder Woman, The Legend of Tarzan, Exodus: Gods & Kings, and Disney’s live-action Mulan, not to mention a few Top 40 songs to his credit, Howe has tackled multiple genres of film and television be it scoring for a full television series or an episode, a drama or a comedy, or animation versus live-action film. His ability to create emotional diversity within a score, and his multi-instrumentality and work with orchestral scores, make him the perfect composer for SHAUN THE SHEEP: FARMAGEDDON, as evidenced by the film’s BAFTA nomination for Best Animated Film.

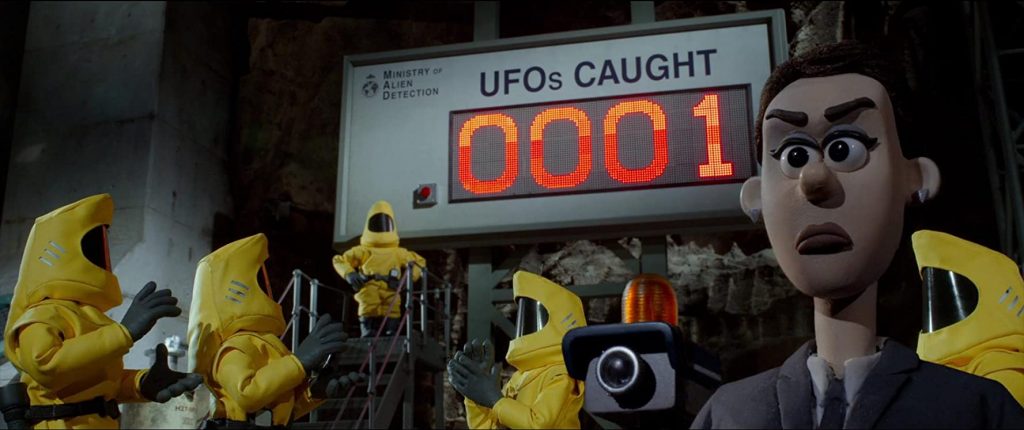

Typically, a composer is called into duty nearing the end of a project when there is footage and at least a rough edit of the project. But because the music serves as the dialogue with SHAUN THE SHEEP: FARMAGEDDON, Howe was brought on long before anything was even in a production phase let alone a “recording phase”, with only storyboards as his guide. He worked closely in a continual back and forth with the directors, first-time helmers Will Becher and Richard Phelan, and the film’s animators. As he related during our exclusive interview, the process was intense and time-consuming, requiring many hours of score over the course of multiple years, some used and some not, not only creating musical dialogue, but emotion and, for the first time, taking Shaun’s adventures into outer-space and the alien world thanks to the adorable new character, Lu-la, who lands at Mossy Bottom where it’s up to Shaun and company to help her return home and prevent being captured by the Ministry for Alien Detection. This opened up the opportunity to pay homage to well-known sci-fi cinematic motifs, as well as creating a symphonic musical journey that becomes more robust and intricate as Shaun and Lu-La’s adventure unfolds.

Upbeat, energetic, and passionate about not only his craft, but musical storytelling, TOM HOWE goes in-depth talking about SHAUN THE SHEEP: FARMAGEDDON, its challenges and its rewards, and the excitement of trying something different.

I am a huge admirer of your work, Tom. I fell in love with what you did on a couple of little indie films, Lost and Found and Is That a Gun in Your Pocket?. As different as night and day, but both of those are just fabulous. I then had to go find more stuff of yours to listen to. So this is a real treat for me to get to talk to you about “Shaun the Sheep: Farmageddon”

Wow! I appreciate you making the time.

The bulk of this film, the “selling” of this film, falls on you and your musical composition and instrumentation because we don’t have any dialogue. Your music is actually the dialogue for this film. How challenging is that for you as a composer? I know normally composers come in, with rare exceptions, they come in near the end of post-production where there are visuals, editing, pacing. But this is not only animation, but there’s no dialogue for the animators so they have got to have music or something to work from. So I’m curious about the challenge of this.

That’s right. As you say, normally, I mean even on some of those films like “Lost and Found”, the movie was sort of in shape. There was a cut and then the director would come and sit in and I’d write and they would change the picture, but fundamentally they had a film in place that you will then try to kind of add to or not do too much to certain scenes. But in the case of this one, as you say, what made it unusual is I came on about 18 months or so before I actually recorded anything. I was finishing up their last film “Early Man”. I was in London at the mix of that and they took me out for lunch and told me about “Farmageddon”, showed me some slides, but I had to start straight away because with the lack of dialogue, as you said, they were sort of sending things to Studiocanal to say, “What do you think of this?”. At that point I was working with very amazing storyboard artists. They had all of the project, but without any dialogue, nobody knew what was going on half the time in the scene. So I wrote from very early to sort of almost sell those storyboards to the studio. I’ve never done that before. I’d get a quick time movie and it was just pictures that were changing every few seconds. And someone would say, “the character here is feeling insecure” so we need some music to highlight that so we can tell the studio what’s going on here. So I think I ended up writing about five of hours of music of this project because I had so many things that the studio would then comment on and a scene would go and something else would come in its place or the tone would change. And the production itself , I think in total there are three or four years on it. But along the way there were changes in some of the characters. Agent Red, for instance, the kind of baddie, was originally, instead of being Agent Red and the robot, it was really two characters, Agent Red and Agent Black. I had different material for the two of them and then I had to change that when they went down to one and then she had a backstory. So I needed a tune that could work emotionally as well as be scary. So things were permanently shifting and I had to roll with that. A good example of that is about a year ago or a little bit longer they had the screening at AFM of four minutes of footage. I scored that and it was a big action sequence and I think I spent about a week on it. It was so fast and so busy and I had to hit so many moments. After that screening, I thought, “Well that’s one in the bag!” Of course, that whole sequence just changed and disappeared and that music ended up going in the bin, in the trash. It never made it into the final movie. It was very much a kind of permanently shifting thing that I had to move with and adapt things and move forward. So, I think it was about five hours in music in total that I did.

Something that I love that you do with this score is that you really take us on a musical journey. We start out and we’re on the farm, but this is the first time that we’re not just on the farm with Shaun and his little sheep friends. Now you’ve got all of outer space to work with and you incorporate this fabulous instrumentation. You start out with banjo, with plucky stuff, with whistling that’s very, very much associated with farms. But then you take us all the way up into space and as aliens appear we’re getting little motifs in there, the “Independence Day” theme, we’re getting notes of “ET” and “X-Files” and the “2001” fanfare and “Close Encounters”. And the instrumentation goes right along with it. So by the time we’re in the third act, this is really symphonic. I would never expect a musical progression, musical storytelling progression, like this for an animated film.

Yes! That’s one of the things that sort of excited me about it when they showed it to me, because I’m a big fan of that TV series of Shaun the Sheep and I was a huge fan of the first movie, and those films were set on the farm and they stay on the farm. So obviously what you don’t want to do as a composer is sort of overpower the end of the picture which is why often you see in drama where you try and stay well out of the way with doing something interesting, but not getting in the way of the dialogue and things. But with this, the thing that I’d say was exciting was after that sort of initial prologue, which is kind of almost its own big thing as part of the score, I tried to make it as you just start in the farm world and then add elements to arrive at a full symphonic score at the end. I knew that I was going to be in Abbey Road for six days at the end. They did want me to use the orchestra. But having all those colors, you don’t often get to do that, to have them in there with banjos, as you say, and then move forward to adding more and more orchestra. Even along the way, for the hazmats who are the kind of henchmen, I was trying to think of a tone for them and in the end someone in a meeting said, “They’re a bit like the Keystone Cops.” And I thought maybe I can use a sort of really upright tack piano with something bonkers going on around it and all these things then kind of came together. But as you say, the score starts and builds to very much a symphonic score for the last act, so that was interesting to me. I had alot fun doing it.

As I’m listening to this, when the Farmageddon stage is being built, all of a sudden we’ve got drums coming in. It’s very upbeat, it’s very poppish in what we’re hearing. And when we’ve got the ship crashing on earth and the little alien can’t get home, the instrumentation is beautiful and a needle drop gets thrown in there. And then we end up with flutes, strings, chorale, and it sounds like a bassoon and French horn. Ultimately, in that climactic third act, you bring in each one of these instrumentations so seamlessly. And each one speaks to an emotion.

Thank you. Particularly with the woodwinds, I played the clarinet and the cello, so those are sort of sections of the orchestra that I feel like I hopefully know relatively well. But it’s also kind of finding the right colors to blend. So when the flutes come in near the end section, as you say, I’ve got it doubled with a harp but also the synth that is used for the character Lu-La. So hopefully you keep a kind of constant of something that has been before so that even when the sound world is changing there is something that binds it all together. But that was the plan anyway. I think hopefully it all feels like one thing. It was a real challenge.

Listening to the score is an adventure in and of itself. It’s a beautiful sonic adventure. Now, because we also have a lot of sound effects in this film, did you have to worry about integrating the sound effects with the score or did they just pop them in after the score segments were done?

First, thank you. But no, often I don’t. I just turn up at the dub on a movie and someone else has done the sound effects totally separately, and at that point you can sometimes be competing to have your stuff louder. But in this case I actually, the sound mix was struck with Adrian Rhodes. He and I spoke early on, so I knew that in certain areas, like when the spaceship lands, he and I had a conversation that he was going to put something in there that was going to suck up a lot of the low end. So I tried to stay out of the way of that and I had the strings going higher there and things like that. Then there were moments where I was told the music was going to feature and I didn’t have to worry about that. So he and I did have conversation about that. That was also what made this project very unusual is that I interacted with a lot of departments that I don’t often get the chance to work with. I’m usually working with the director and the producer and that’s kind of it really. But in this case, they set me up a little composing room next to the edit room and I would go over to Bristol in England and I would hang out there for three days, roughly every three months. And I would write with them there. I would get to go on the set and talk to them before they had the shots done. I’d get a sense of what the scale of it might be in the bass or what they might be looking for without having the picture until it’s fairly near the end when they were completing the animation. I’d also have these meetings, a lot of meetings, with the editor. And as I said, Adrian and I spoke a lot and I got to spend a lot of time with the animators, talking about the colors and things and where this is going to be dark bit, and so forth, and I knew therefore, I could do something dark with the music. So it was quite a collaborative process. I mean, across the whole film really, which was great.

You’ve done so much television, so much scoring for television of all different types, but a lot of the TV work that you’ve done is much darker than the thematics, forget about the animation, but just the thematics of Shaun the Sheep: Farmageddon. Now that you have done Farmageddon, do you have a preference to doing these lighter tones, more challenging tones than the darker notes of a lot of these series?

I think I enjoy animation in whichever form it comes. You really get to kind of work to the picture in a way that you don’t necessarily in other genres. But one of the things that excites me about composing fulfillment TV is how different each job is and how that comes with its own set of challenges. For instance, at the moment I’m on a TV series for Apple and the whole thing is band, guitars and drums and bass and things. And I’ve got my guitars out, my pedalboard and things I haven’t used in a year and I’ve got them all turned on in the studio and I’m trying to kind of figure it out. But that’s what makes it for me. That’s what makes me tick, if you know what I mean. Each time I get the call, if I’m lucky enough to get the call, it comes with its own set of challenges and I have to then think. In this case I’m thinking detail about what microphones I’m using on the amp to make it authentic for that sound and whether I’m using a Fender Strat or a Gibson and things like that. So each project, to me, each one being unique is what makes it exciting. I prefer if I’m there purely from how I feel at the end of the day. Doing the light stuff tends to put me in a better mood when I go home than when I’m doing something really dark and depressing, But, both of them come with their own set of challenges and that to me is what keeps the whole thing kind of exciting.

This is your second time working with Aardman. Talk to me about the experience of working with them. I’ve talked with a lot of composers who do tons of stuff with Disney, which is its own animal. But Aardman, their animated stuff is “irreverent,” it’s out of the mainstream. Early Man is, again, a pure joy. I love that film. And I love Shaun the Sheep: Farmageddon. How is this different, this collaboration with Aardman, different from collaborations with other companies when you’re doing a full series or a film?

I think mainly from that point, because it takes such a long time for them to make it, they pour over everything in a lot of detail and the company unlike say working for a Disney, as you said or something, where people… I did something for Disney a couple of years ago and the person I worked with is now no longer there, they’re somewhere else. The thing that makes Aardman really unusual is that the line producer who I kind of dealt with on a daily basis, he’s the same person who was on Chicken Run. The person in charge of the music budget is the same person who’s on “Chicken Run”. And they almost, it seems the animator who, sorry, both the directors who were on “Farmageddon”, one of them was an animation director on Early Man and the other person was a lead storyboard artist and they’ve all been there for 10, 15, 20 years plus. And that’s what makes it unusual. So even now I’m hoping to do something else for them coming up in May. When they called me about it last week, the person who called me, I’ve met him on the last two projects, but he’s also been there forever. They don’t really leave and go anywhere else it seems. So it comes with its own eccentricities that is unique to that company. And they’re all so humble. And the first time I met Nick Park, we went to the pub and we had a beer and he’s just chatting about, he listened to something I’ve done and he’s excited to kind of move forward with, he’s so down to earth he’s forgetting he’s won five Oscars or whatever it is. They’re just incredibly normal and down to earth and they all just stay together and don’t really go on. It is his own thing really. So I think that’s what makes it so different and the same people across everything means that each film has its own unique Aardman star already.

Well, I really hope that Nick’s golden touch rubs off on you so that you’ll be up there getting an Oscar one day.

I always pinch myself when I get to just do this and make a living at it, particularly now at the moment in the current climate. There’s so many great things being made by so many different people. So there’s so many opportunities as well. I think we’re finally arriving back to that place where for the last, I don’t know, I want to say definitely five, six, seven years, there’s been the main studio doing X number of films a year and the kind of stuff that isn’t under $80 million doesn’t get made unless it’s very low budget in the one, two million dollar type stuff. But now it feels like lots of things are kind of now finding homes on the Netflix’s and the HBO’s and now there’s Peacock coming and all these things. I think it’s a really exciting time just to be in the industry because people are making really original stuff again.

And they’re paying attention to things like score, be it television or film instead of just throwing something, 1970’s canned or something in there for a genre. I find that very exciting.

Yeah. And I think there’s a lot of exciting new people coming through who are doing really interesting things. I watched Uncut Gems the other day and I know everybody has watched it, but the score is nothing like I’d expect, nothing like I would have approached. That is exciting. That is coming to the forefront and getting talked about and just lots of different ways to skin the same thing. And I think that because of the amount of stuff being made it’s just going to be exciting time for not just music, but makeup artists and animators and everybody kind of moving forward.

One more question before I let you go, Tom. Because of the challenges with composing for Shaun the Sheep: Farmageddon that really pushed you further than I think you’ve ever been pushed before, musically, what did you learn about yourself in composing for this film that you’ll take with you into future projects or that you’ll consider when you’re looking at future projects?

The thing that probably I learned the most about, I mean not just about filmmaking but about the music, is that they often, as you say, I get stuff where I have to do it in quite quickly. And so I have to run with an idea fairly early on. Otherwise I’m simply going to run out of time. I beat myself up for weeks trying to come up with my themes on “Farmageddon” and then I tried variations on them, every which way I could think of in different modes and a whole different sort of scale and rhythms, until I was sure that I had all the kind of ammunition I needed before I then went forward and wrote any of the cues really. I try to do that on everything, but I don’t always have the time to keep going back and deciding I could have done it a bit better. So I need to basically get better at doing that faster. The next time I can do that, I would hopefully do it a bit faster. So I’m hoping I can sort of take that forward. On Lost and Found, I really enjoyed working on it. I think I had five weeks to do the whole score and obviously that’s not a lot of time. It was 80 something minutes of music and the director was sitting behind me on the sofa in the studio the whole time I wrote the score. So you obviously work in a different way, also you don’t have time to really make mistakes because you haven’t got a lot of time. But also at that point they might panic and hire somebody else. What I found really unusual about this one that’s refreshing and hope I can get on lots of things early moving forward, is that I could throw out the most ludicrous ideas which they’d shoot down and then I could move on. But at least I can have a go at trying something different before I then try something else or whatever. And [Aardman] was open to that. So I think that farm opening when the farm comes, the version that’s actually in the film, I wrote in the room next to the edit when I was there with them. But I had a lot of other goes at that first and it wasn’t concerning for me that I just tried lots and lots of different things really. So that was interesting and sort of unusual. I hope I just get faster. It is nice if you have the time to finesse things and we never ask, but I think probably with every department in a film, we keep tweaking it until it’s gone out the door. You always try to make it better as you’re going along. So I think sometimes more time is helpful. But when you’ve got no ideas, I think less time is good. You have to do something.

by debbie elias, exclusive interview 2/21/2020

SHAUN THE SHEEP: FARMAGEDDON is streaming now on Netflix.