Cinema 2017 may well go down in history as the “Year of the Cinematographer”. While there is always standout cinematographic lighting, lensing, and storytelling, 2017 boasts a plethora of truly exceptional work by truly exceptional craftsmen who each take visual storytelling to new heights and new emotional levels, among them, Ed Lachman, Rachel Morrison, Mandy Walker, Tobias Schliessler, Robert Richardson, Roger Deakins, Kevin Garrison, Wyatt Garfield, and DAN LAUSTSEN.

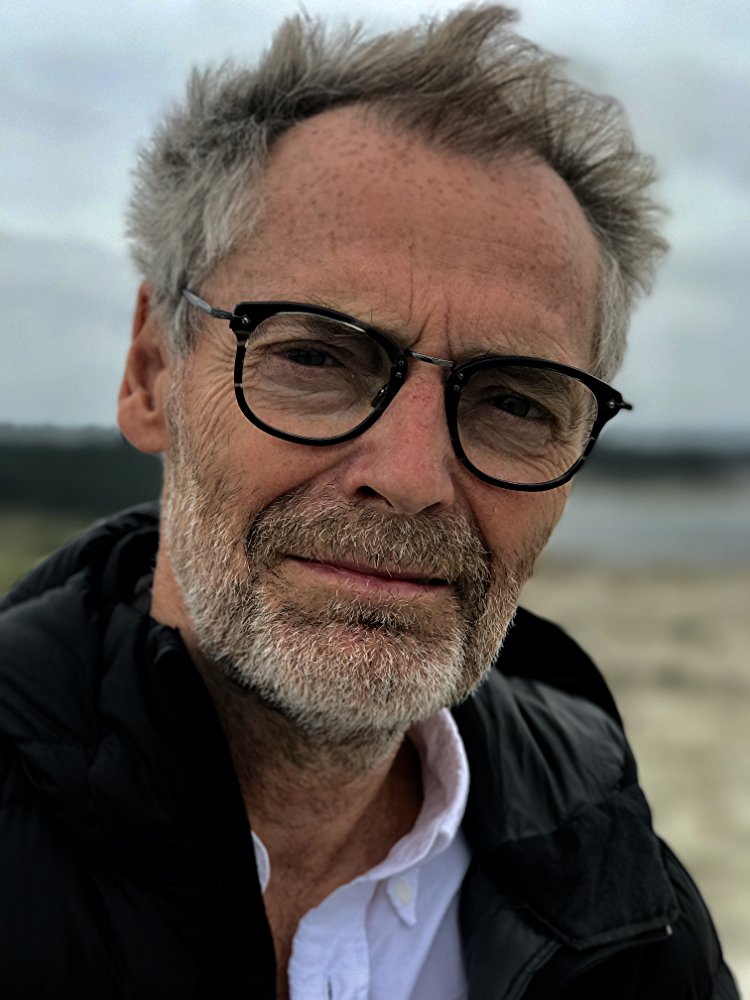

With almost 40 years as a cinematographer to his credit, Dan LaustSen’s resume speaks for itself thanks to films like the blockbuster “John Wick: Chapter 2″ or Ole Bornedal’s “Deliver Us From Evil”, “The Possession”, “Silent Hill” and “Nightwatch”, not to mention Stephen Norrington’s “The League of Extraordinary Gentleman” and “Solomon Kane” directed by Michael Bassett. But it’s Laustsen’s collaboration with Guillermo del Toro that has created some of the most defining and exciting works of his career, starting with “Mimic” and on to “Crimson Peak” and now, THE SHAPE OF WATER.

Set in 1962 Cold War America, “The Shape of Water” melds the line of fantasy and reality, taking socio-political elements of the day – Communism, espionage, a transitioning JFK America, disability, sexuality, sexual orientation, sexism – and a good old-fashioned romantic love story, bringing it all to life with indelible, passionate performances by Sally Hawkins, Octavia Spencer, Doug Jones, Richard Jenkins, Michael Stuhlbarg, and Michael Shannon. The result is not only breathtakingly beautiful, but emotionally charged, captivating the senses, the imagination, and the heart.

One of the most exquisite cinematic experiences not only of 2017, but in the history of film, THE SHAPE OF WATER is perhaps the hallmark of DAN LAUSTSEN’s career to date. Meeting challenges of space, color, character, and above all, water, I spoke with Laustsen in depth about the cinematography of THE SHAPE OF WATER and his collaboration with Guillermo del Toro. Enchanted as much by Laustsen’s Danish accent as by the film itself, the excitement in his voice is palpable as is his passion for the project and the emotional and technological challenges of water, smoke, epoxy, latex, Gobos, and more, as presented by del Toro’s vision.

This is, to be honest, a visual masterpiece. And your most exquisite film to date. Without the way you have lighted and lensed this film, it would not be what it is. There’s great movement of the camera that metaphorically mirrors the movement of water and the movement of emotion. And your lighting! It’s very non-traditional lighting. You really celebrate shadows and you make them work. But then you have the creature. So often we’re used to creatures being hidden in the shadows, but here, the creature is celebrated by being in the light when he’s around Sally Hawkins’ character Elisa. How did you go about designing the lighting look for this, Dan?

Thank you! Thank you very, very much. I’m glad you like it. You know, the first time I heard about this movie was when Guillermo and me were shooting “Crimson Peak.” “Crimson Peak” was a very colorful movie and I liked what we did there. I think it was amazing. I was really pleased about everything about the movie, but it didn’t do so well. But that’s another thing. [laughing] So Guillermo one day said to me, “You know, we have this movie I want to do. It’s about a girl that cannot speak and she’s falling in love with a fish-man.” And I said, “All right?!?” And he said, “I want to shoot in black and white.” And I said, “Oh, that’s fantastic!” because all the cinematographers on the planet want to shoot a black and white movie. So it was black and white for like five minutes and then it got tossed away and then we went into color. Guillermo and me, we’re going back together to Munich, 20 years ago or something like that, and we have the same taste about darkness and blackness and we’re not afraid of the darkness or the deep shadows. But on this movie, he talked about that we want to go back to the old Hollywood way. Of course we cannot do the Hollywood black and white look in color because that’s never gonna work. But he wants to do the single source lighting. Sally [Hawkins] has to look like a princess all the time and the creature is just a creature in the beginning. Later into the movie, the creature’s going to be like a real person. . . kind of. I don’t know if “it’s” a person but that character needs a lot of love with the lighting and that’s what we did. There were real characters and real human beings but it was very important to have this atmospheric feeling about the movie. It still has to be a dark movie but the actors have to look amazing. We were lighting them very, I would say, the old Hollywood classic way where the females have to look beautiful and the guys have to look very strong and powerful.

When it comes to the creature, because of the foam latex of the bodysuit on Doug Jones and the epoxy paint that was used so it wouldn’t peel off, did that affect the lights that you chose to use at all in terms of reflection?

No. The first time I saw Doug [Jones] in the suit was when we were making some hair and make-up tests for the rest of the cast. So we shot some tests with cold light, you know steel blue, greenish. Some was a little bit more warmer. We did a color light test for him. It didn’t work out so well. [laughing] Guillermo was just an amazing director because he just knows exactly where he wants to go, and that’s so much a pleasure to be together with guys who know exactly where to go. He’s not telling you what to do, but he knows what he wants to do in the scene. So we saw that make-up test and after that they repainted the creature, but that was close to principal photography. I think it was more browns in the beginning and then they painted into this more green and blueish, as it is right now. But talking about lighting, I didn’t do anything special. I was treating him as he was a real person because I think the suit and the makeup, the creature was done so much fantastic and so much with a lot of feeling. Of course we still have to light him with a lot of respect for the shadowing, but there was nothing we have to hide. We just have to show his beauty and his strongness. I think that’s a part of the design of the movie, of the creature. We didn’t have to hide the creature because the creature was not good enough. The creature was just so beautiful made so I could play it as there was a normal person. And of course, we changed that all the time because we are painting with light so it depends what the scene has to tell. In the beginning he’s always lit with steel blue, cyan, green. Then, for example when they’re falling in love, and it’s all in the bathroom, we’re changing the lighting into a very, very warm golden atmospheric. So the light is just trying to tell a story with that as well.

Something that you also do that I think is so beautiful, that creates a great subconscious connection for so many people, is that you bathe Elisa’s apartment with light. It’s very cool with that almost inky blueish tint to it. And it goes with the whole idea of water and the creature. By contrast, the other half of Eliza’s apartment is, in actuality, Giles’ apartment. They just have a wall separating them, something that you can see thanks to the quarter half dome window section in each apartment. But the contrast between the two apartments is stunning.

Oh, thank you! When Guillermo and me are a making a new movie, he’s making some concept about some various colors, design of the set, and we’ve got design of the creature and stuff. But it was very clear for us that [Elisa] has to live in this dream world. She is doing the same thing every day. She’s waking up, she’s masturbating, she making the cakes, you know. She’s just living her own world. And because it’s this fish world, you know, a water world, we were going green, blueish. The rest of the world is outside her door. In Giles apartment, that’s more golden and more neutral. That was very clear for us from the beginning, that was the way it should work. And nobody’s question marking, “She’s blue and he’s normal.” You just buy that.

You do. You accept it automatically. There is not a moment that feels false when you see this. Something else that really works, especially for me being a lover of Hollywood movie musicals of the Golden Age, is the black and white dance number. Dan, it is so beautiful and the way you have it lit, and the way you lens this, I’m thinking you were using Technocrane to shoot it. But it really picks up what Luis [Sequera] did, especially with Sally’s costume. I know it’s a multi-layered skirt of fabric and he’s got crystals right underneath the top layer so as she moves, the light hits the crystals and your camera picks it up and it is gorgeous. It’s like looking at Gene Kelly lensing Barbra Streisand in “Hello Dolly” or Stanley Donen lensing. Absolutely stunning.

Oh, thank you! That’s very good! We had this idea about the scene that it should be black and white, of course, and then we want to shoot it more as a classical Hollywood, as you said, musical scene. So you know, the rest of the movie is shot on Steadicam, dollies, hard hats you know, where the camera can move more as floating from one cut to another. The way Guillermo designed his editing is that it’s floating from one floating camera movement to another floating camera movement and I think that’s the reason it feels like you’re floating in water in the whole movie. But when you’re coming to the dancing sequence, we shot everything on the crane so it’s going to be more normal movements in and out and booming up and down and panning to left and right. And for the lighting, I knew we will have this costume. I saw what the costume designer was making and Guillermo showed it to me. Of course, we want to have this feeling about a 50’s Hollywood glow. So we were shooting that with follow-spots. We were lighting the sets, the normal set, but we would follow her with a follow-spot so we got that kick off into the camera where we have a diffusion filter that was kicking up all the small reflections on the costumes. I think that was one of the keys which works pretty nice. We were doing very, very old-fashioned lighting there.

I could watch that sequence over and over and over again. I would love to see that pulled out and made into its own little music video. It’s that beautiful.

That’s so nice to know, fantastic, I’m so happy! I’ll have to tell Guillermo! Thanks.

One of the keys to your entire lensing is the fact that you’re using the Zeiss Master Primes.

And the reason I’m doing that is because I like to have lenses that are unforgiving. Master Primes are so sharp and they’re not flaring, they’re not doing anything. I know what I’m gettting. It’s going to be one-to-one and I really like that. I don’t want to put a lens in the camera and I’m not sure what I’m getting. So everything what we are getting from the Master Primes is something we are putting in in front of the camera. The black is going to be really black. The highlight is going to be just before it burns out. But all that is something we are designing. I think there’s nothing on the movie, or very, very little … of course, you have some accidents now and then or some mistakes, but most of the movie’s very, very well designed from Guillermo and my side, you know lighting-wise and camera movement-wise. All the colors, when we’re coming into the DI, we’re not changing any colors at all. All the colors on the movie is coming from when we are shooting the movie at the set.

It is exquisite and of course, you can always add a diffusion filter if you need to, such as with the dance number.

The whole movie is shot with a small filter, I think a black ProMist, inside the camera. We have a very slight diffusion filter inside the camera for the whole movie because we think it was getting a little bit too sharp on Sally without the diffusion filter but I didn’t want to go to a worse lens. I want to go to the best lenses I can buy for the money … or rent for money. [laughing] So we did that. I don’t like to have a filter flare. You have these very, very nice lenses and you put a piece of glass in front of that so if you got a flare, you’re getting a filter flare, but I really don’t like that. I like to have a lens flare. But that’s a reason when you’re shooting with Alexa XT, you can put a filter behind the lens. We did that, the whole movie is shot with that and I think when we come to the black and white dancing sequence, we just put a little bit stronger diffusion filter in there.

That’s amazing. The look is so rich. It’ saturated. It’s beautiful. I have to ask you Dan, about what some directors think would be absolutely the worst thing in the world to do, while many who love old Hollywood and old technology think it’s the best thing to ever get to do – – shooting dry-for-wet and working with smoke in order to capture what would eventually be water sequences. How did you go about working with the smoke and creating those looks in the “iron lung” and also in the vertical tank that the creature gets housed in? I’m very curious about working with the smoke for the dry-for-wet.

First of all, we have to remember, this is a small movie. This is a $19.5 million movie. We were very tight budget-wise. We were very tight money-wise all the way around. We was carrying as small a camera package as I’ve used for many years. The whole movie’s shot, more or less, with one camera. Of course, you have two cameras but we were was carrying one set of lenses so it was a very tight camera package because we couldn’t afford anything. We had a lot of discussions Guillermo, with visual effects guy Dennis [Berardi], and myself about how to do this opening and end sequence. We were talking about wet-for-wet and wet-for-dry, how to do it. First of all, there’s not a big tank in Toronto where we shot the movie, and we could not afford to go to another place. Guillermo was, of course, very nervous about having his actors into water and everybody understood that so we start to make some tests from dry-for- wet. It’s an old technique and people have done that for many years. Sometimes it looks as it is. It looks like you are not underwater. Of course, we didn’t want to make that mistake so we shot some tests and what we did was, we made a kind of a Gobo. We shot a plate, a moving plate for the water, then we put that into the computer and we bring that image into a film projector. We were lighting the smoke, this very, very heavy smoke, with lights that were moving around from a film projector. I think that’s the reason it works pretty well because it really feels you’re underwater because you see the light moving around. Of course, we shot a little bit slo-motion, and the visual effects guys were putting some fish in and bubbles and all that kinda stuff. But the main look was coming from the smoke and from this moving light from the film projector. So those scenes are totally lit with film projectors, the beginning and the end.

As I was watching the film, I actually wondered if Doug [Jones] was actually placed into a tank of water. For so many of the scenes where the creature’s in the water. It’s seamless. You cannot tell.

The only scene that’s shot in water, wet-for-wet, is when they’re in the bathroom. That sequence that she’s closing the door, she’s filling the bathroom up with water, there’s a couple or three or four shots there that’s shot in water. As I said, we couldn’t afford to go to a big tank somewhere so we built the smallest tank on the planet that was like five feet bigger than the bathroom. We took the bathroom out of the set, put it in another studio, built some plywood walls around it and we filled that up with water. It was so simple. But it worked really well and that was the only thing that’s shot wet for wet.

Did you do any actual underwater photography with this one?

That scene was. That scene I’m talking about is underwater. Underwater photography. You know where they’re making love in the bathroom and Giles are coming in and opening the door? That scene is shot wet-for-wet. But the beginning and the end is dry-for-wet.

For you as a cinematographer, when shooting the dry-for-wet, with the smoke and the amount of smoke, does that present a problem at all? Any kind of challenge?

It’s really painful to be in all that smoke. It’s really not fun because we’re talking about heavy, heavy smoke. You cannot see yourself. It’s insane and you just have to know where you want to go. We have that luck, we shot some tests so we were sure. Especially the end sequence, those shots are pretty wide so we have the film projectors on the cherry picker. I can’t remember what it was, forty feet high or something like that, and it’s a little bit difficult to control it because the problem is when you’re putting lights on the actors, if you start to put fill-light on, for example, you see that in the smoke right away and that’s going to kill the illusion. So you have to backlight them and toplight them all the time.

Were there any particular lights that you were using for the backlighting and toplight?

The backlighting was just a normal 1K, a normal fill-light because it was just to silhouette them. The key light was coming from film projectors. The key light was moving around but the backlight was just to separate them from the background. You know when they’re hanging there in wires and you see them floating close to each other and embrace? The keylight was coming from film projectors and the backlight is just a 650 on the ground. Just to make a separation from them in the background.

I would be remiss not to ask you about lighting the office space within the laboratory bunker. It has a wonderful contrast to some of the other scenes that we have in the film. Having that glass office overlooking the lab floor and then you’ve got a colder light going in there.

That’s because we want to have the difference between this Cold War bunker and the rest of the movie. The glass room is lit with fluorescents and of course, we’re switching them on and off because even when you have fluorescent light, we want to have the contrast single source lighting. If you are shooting realistic in the fluorescent-lit room everything is going to be flat. So the master is the light coming from the fluorescents but as soon as we’re getting into medium and close-up [shots], I’m just changing the lights so it looks more dramatic because in the real world, you will never get so “contrasty” light from the fluorescents.

I think we all know how bad we all look in fluorescent light in real life!

Exactly! [laughing] No, what I did there, as soon as we were into medium and close-ups, I just changed the lighting. And what we’re doing all the time, Guillermo and me, is we’re just changing the light so the actors look nice all the time. Automatic. We want to tell the story with the lighting. We don’t want to be realistic. Of course, you cannot get crazy, but we want to change the light so Sally looks great from that angle. In the main room, that room below that office, I didn’t want to have fluorescents there because I didn’t want to have it bright, so I was lighting that with PAR cans. We could make some pools of light and we could just switch them on and off, but I wanted to have this feeling about, it’s a dark room but still you see what it is but it’s not over lit. So that was done with PAR cans and if I remember correctly, it was LED to PAR cans so we could dim them up and down.

Do you like working on a film like this, Dan? A film that has a limited budget, that really pushes you and challenges you to find ways to achieve what you need cinematically?

Yeah. I think that’s fun, as long as you’re on the same page as the director. It’s so cool to be together with a guy like Guillermo because he knows where he wants to go and we are speaking the same language. We just want to do it as simple and good as we can. It helps a cinematographer a lot, of course, to be together with a director that doesn’t want to shoot everything from a million angles because he’s not sure what he wants to do. That’s helpful of course when your schedule is so tight.

How much time did you have to actually prepare? In pre-production and then how much shooting time did you have?

I think I had eight weeks. Obviously that’s too short, but that’s the way it was. And then we were shooting for 55 days if I remember correctly. And we have a B-camera hanging around all the time but we never used it more or less. Poor guys. Something so that you know – – the egg was boiling, some of the driving shots with the cars and stuff like that, that was B-camera that did that. But otherwise it’s single camera set-ups all the time and that’s the only way you can do that because the light is so precise. The challenge of this movie is because the camera was moving so much, so the lighting was from where the camera was starting to where it was ending, that was moving a lot so I have to move the light as well. Some of the light is handheld so we are carrying LED lights from one position to another position to keep this contrasted look on Sally, for example. So you’re not starting very contrasted and ending in flat lighting. We were trying to avoid flat lighting as much as we could.

Well, I have to say, Sally looks absolutely exquisite in this film.

Thank you. She’s a wonderful actor and she can take this light. It was very important for us she should look like a princess all the time so what I did, I would double diffuse the key light on her all the time. I was double diffusing her all the time and sometimes we have, in the old day, the old-fashioned things, we have a small tree above the camera just to open her eyes up a little bit now and then. Like they did in the old days. So we did that. And we did that a little bit more and more further into the movie where she has to look more like she was getting into this dream world. The challenge is to light actors beautiful all the time when the camera’s floating around all the time and you never know where the camera is, but that was fun and a challenge.

The result speaks for itself with THE SHAPE OF WATER.

by debbie elias, interview 12/08/2017