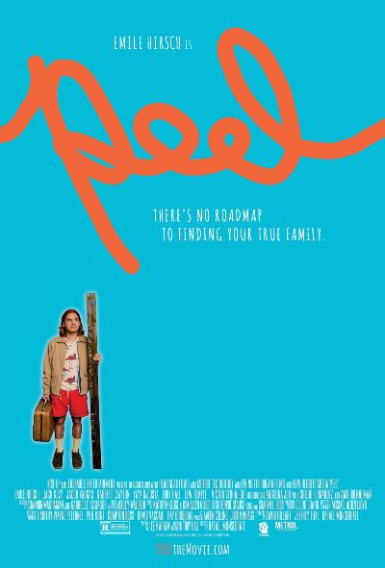

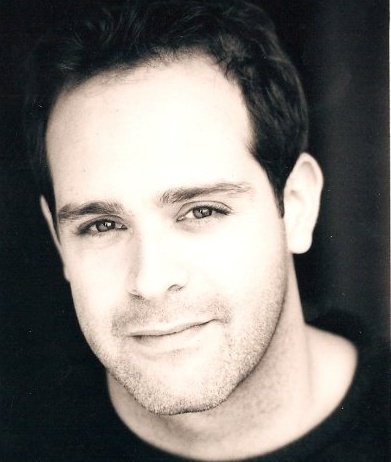

RAFAEL MONSERRATE has long proven himself to be an accomplished documentary producer thanks to television series documentaries like “Alone”, “Hillbilly Blood”, “Whale Wars” and more. He also stepped into the television directing arena with several episodes of “Mafiosa” and some reality-based projects. Feature films, however, but for comedy “The Dissection of Thanksgiving” more than a decade ago, have eluded him. That ends now with the enchanting charmer PEEL.

With an almost magical feel, PEEL is a celebration of innocence that not only melts your heart but makes it smile. Through cinematography and music, Monserrate finds the humor and heart of life, tonally and visually, while finding the humanity within each character thanks to some memorable performances, most notably from Emile Hirsch and Jack Kesy.

Directed by Monserrate and written by Lee Kariam with additional material by Troy Hall, PEEL is the coming of age story of Peel Munter, played by Emile Hirsch. Abandoned by his father as a very young boy, Peel has led a very insular and lonely life. When his father left, he took Peel’s two older brothers, leaving Peel not only alone with his mother, a woman with psychological issues, but with his memories and longing for his brothers. So severely cloistered by his mother, Peel has no social skills, no life skills. He has had no real life beyond the confines of the walls of his childhood home. But within that world, Peel has had one constant – swimming in the big kidney-shaped pool in the backyard. That has been his savior and his joy. On the unexpected passing of his mother, Peel is adrift. 30 years old and he doesn’t know what to do. He has no friends, no job, no money, no skills. What he does have, though, is his home. But his mother left that with a large mortgage and that means mortgage payments.

Facing the uncertainty of the world, for the first time in his life Peel is forced into making a decision. Does he venture into the world and find a job so he can stay in his home? Does he sell the house? But if he does, where will he go? Does he just stay in the house until he’s kicked out? Peel Munter decides to take a very big step. He decides to take in roommates. Not only will that take care of the mortgage issues, but he might even make some friends. But what happens when the unconditional faith, friendship, and brotherhood Peel extends and believes to be “real”, is betrayed? In Peel’s case, it puts him on a path to find his real brothers and in his journey, he touches the lives of all he meets.

Emile Hirsch not only embodies Peel Munter. He IS Peel. Bring a refreshing naivete and wide-eyed wonder to the character, with subtlety and nuance, Hirsch brings Peel’s innocence to the forefront, endearing him to us while drawing us ever deeper into the character and the story. It is joyful to watch this character and Peel’s cynicism-free approach to life. Simply charming.

A great performance comes from Jack Kesy who serves as a perfect counter to Hirsch’s Peel. As drifter Roy who makes his way into Peel’s life as a roommate and “friend”, Kesy brings Roy to life, embodying the idea of a man who is half in-half out when it comes to life, but always making us believe that for every con or less than upstanding thing that Roy does, there is true redemptive value in this man. When we first meet Roy, he is talking a mile a minute, rapid fire; he’s pulling a con game on everyone. But the deeper Roy gets into truly knowing Peel and being a part of his life, Roy’s temperament, his cadence, it comes down, it slows down, there’s less dialogue for him, there’s less hustle. He becomes more introspective and observational as opposed to trying to take charge and cover up his own insecurities. Kesy makes Roy one of the fascinating character studies in the film.

Other supporting players are equally standout and emotionally powerful. One look at Garrett Clayton and his performance as Chad, or Shiloh Fernandez as Peel’s addict brother Sam. Each is just as good as the other, yet unique unto themselves. Notable is the physical nuance Fernandez brings to Sam when confronted by Peel after being separated for 25 years. He will not raise his head. He will not look Peel in the eye. He hangs his head and the shoulders slump in shame and embarrassment for who and what he has become. And then Hirsch swoops in with Peel’s non-judgmental emotional purity and makes the pairing soar. Truly some magnificent character studies in PEEL.

Going beyond performance, Monserrate finds the humor and heart of PEEL, and the humanity within each character and the film as a whole, through his visuals and the work of cinematographer Michael Lloyd and his team. With water playing a central theme in Peel’s life and mindset, Monserrate and Lloyd dazzle with underwater lensing courtesy of camera operator Jen Baumert, metaphorically celebrating light as being reflective of innocence and the rebirth of baptism and purity through water with gorgeous sunflares and prismatic color. Color also plays a significant part in creating the world of PEEL as there are two distinct worlds within the Munter family home – that of Peel’s childhood and his mother with time standing still in the 1970’s and 80’s with design, color and lensing, and that of Peel within his bedroom and “shed”. The Munter home is basic, plain, muted and filtered light as if sunlight barely makes it through the curtains but when it does, it has the softness of a shroud. On the other hand, Peel’s room is bright using vibrant color contrasts to reflect his upbeat and positive persona; and shades of blue and aqua form that thread of continuity with the importance of water to Peel and to the story. Lloyd’s camera also adds a layer of storytelling through framing, using dutching or overheads, and frames slightly askew or off-center when a one-shot on Peel, while the remainder of the film is lensed relatively straightforward with symmetrical framing and balanced mid-shots.

The icing on the cake and the world of PEEL is the scoring by Kathryn Kluge and Kim Allen Kluge. Simply beautiful. Whimsical and lilting, we feel the innocence of Peel through the score, and are then transported in time, place, and emotion by the individual needle-drop soundtrack selections.

With attention to even the minutest details, Monserrate has delivered an emotionally magical film that is from the heart and speaks to the heart.

Speaking with RAFAEL MONSERRATE in this exclusive interview, Monserrate elaborates on his directorial process and the importance of finding the truth in PEEL. . . . .

I am excited to be talking with you after watching PEEL, Rafael!

Oh, you warm my heart, Debbie!

Well, you melted mine. This film – it makes your heart smile. It’s magical. There is a beauty to the innocence. It is an absolute charmer.

Debbie, thank you so much. You’re giving me chills. I agree with you in the sense of that was our intent, and that’s what we were hoping to evoke in people, so thank you for saying that.

You definitely, definitely evoked it in me. What I find so powerful and so beautiful about the film, one of the elements beyond Emile’s [Hirsch] performance, is how you found the humor and heart tonally and visually. And then, working with your cinematographer, with Michael Lloyd, and all of the water scenes incorporating the whole idea of water as being like a baptismal every time he goes in the water and regains or retains his innocence.

That is so spot on! Spot on!

You blew me away with that, and that fact that each of those underwater scenes you’re shooting upwards. You’ve got your sun flares creating the prisms. Just absolutely flawless.

Thank you so much. Michael’s an incredibly talented DP. I had met with about 20 DPs in the course of two days here in Culver City, California, and he was the first person I met with. He sat down and he understand the themes of the power of the innocence and the stillness of the water and what that theme was, and he understood that that is Peel’s sanctuary, the place where he feels safe, a place where he feels at home, the place where he goes to escape but also in ways to find himself in the stillness. So Michael and I spoke plenty about how to truly capture and find those moments, And we got an incredible underwater shooter, who was fantastic, Jen Baumert, and she understood how to capture that light, as did Michael, who did a lot of planning to recapture through the lens that light, which is gorgeous. We wanted, through the water, to really represent the beauty and power of his innocence. And then, of course, the obvious themes of the womb, and the bond with mom, and that kind of thing.

And the fact that his question to his brothers, “Do you swim? Do you swim?” This is how he sees it. The answer to everything is to be in the pool and swim.

Yes, yes!! That scene with Sam when they finally come home and enter the living room through the back door, and you see Sam’s going through withdrawals, his discomfort, his inability [to function], and he’s trying to stay connected to Peel. And you’re right. What does Peel say? He goes sort of down the list of comfort, “What can I get you to eat? What can I get you to drink? You want to go swimming?” And when Sam sort of barks at him, he doesn’t want to and he sort of rejects him, and then when he joins him in the water, symbolically that is the film. When he joins him in the water, that’s the moment where we’ve all come home with Peel.

Of course, you also bring in part of that with Jack’s [Kesy] character of Roy. A great performance by Jack and the emotional arc, and the character growth that we see here. We never see him get totally in the pool, he’s half in up to his waist, but he never gets all the way in and that plays into the idea that he’s half in, half out, that there’s a redemptive possibility for him.

Right, yes. Yes! That is Roy and that is Jack’s performance and that is his arc. You’ve expressed it beautifully. First of all, Jack Kesy is an incredible actor. He is raw, he is nuanced, he is alive, he’s got so much going on inside. Jack, originally we went to him for the role of Sam. He lobbied for Roy, and lobbied for Roy, and once I sort of met with him we had a Skype meeting, I saw Roy and we changed course. He’s brilliant because he wants to be found and all the stuff that he does in terms of being the life of the party and what he thinks he’s looking for; he’s really looking for a brother, he’s looking for a family. And when he ends up protecting Peel at the end. . . He’s such a wonderful actor and so honest and so true.

My eyes teared up at that one. I’ve got to tell you. I really think you perfectly cast him. I’ve seen Jack in so many other things that he’s done going back to his one-offs in “Ray Donovan”, “The Strain” and, of course, “Claws.”

So you followed a lot of his trajectory?

Yes. So, I know he has that range and he can bring that texture and depth to the character of Roy, and I just love what you elicited from him in this performance.

Thank you. These actors, the whole cast and like you sort of identified with Roy – I was speaking of this earlier, that what all these factors identified within the script and these characters, was this feeling of understanding of what it is to feel like an outsider, like a misfit, like someone who doesn’t belong, and that really brought an authenticity to their approach and to our approach in terms of really capturing that. We all wanted to be honest with what that meant. So whether it was a comedic moment or whether it was more dramatic or whatever it was, our approach was always, “All right. Let’s find the truth in this.” And then these actors are wonderful. They do. All of them are wonderful.

They truly are. Look at Garrett [Clayton] and his performance of Chad, or you look at Shiloh [Fernandez] and his performance of Sam. Each one is just as good as the other.

Yes. Powerful, powerful. Yeah. And so unique unto themselves. Troy Hall as Will has that perfect balance; the two different kinds of brothers and what their issues are. And Shiloh was powerful, and the thing there was the restraint he needed to be able to face his own demons in the face of this innocence in front of him.

And, of course, some great physical nuance by Shiloh in the character of Sam, when he is confronted by Peel in his apartment. He will not raise his head. He will not look him in the eye. And he hangs his head and the shoulders slump, and it’s an embarrassment like he would be chastised by his parents.

That is right, Debbie. That’s exactly right. The shame, the shame.

When you got this script and you’re looking at it, how did you first start sitting down to break this out from a directorial construct as to how you were going to take the words on the page and convert that into visual expressiveness and emotion? Because with what’s in here, you could have gone so far to one end, such as almost like a Forrest Gump which would not have worked. But here you’re exercising restraint and also finding that balance between when to pull back, when to cut, when to … you do a great job of deciding when the hold of the lens is just enough, and you move on so it doesn’t get overly sappy or feel forced. What was your process like to approach this?

That’s right. Well, first off, thank you. I appreciate you saying that, and it’s something that is important to me – just telling a story in the most authentic way possible. But in terms of this story, it first came to me as a very broad comedy. It was big. But there were two things. One was Peel’s inherent innocence that I found to be very powerful and something that I think we need it in today’s environment. And second, the scene with Sam. When I got to that scene I realized, “Wait a second. There’s something much more powerful happening here, and I think the way to find it is not to force it but to allow breath, to allow moments to breathe both in performance and in the lens.” The approach with the actors was, “Let’s discover.” We didn’t have a lot of time. What was it? An 18-day shoot? I had three days of rehearsal with everybody. But the key was “let’s discover, let’s find the breath, let’s find the moment” because anything that feels false isn’t going to work here in the way of the approach that we wanted to make in terms of the power, the authenticity, and the innocence. The other thing was the lens. With Michael, who’s an incredible DP, the idea was let’s only move when we are guided by the character’s movement, and let’s hold. Michael suggested the wide lens, as wide as we could go, the anamorphic, which allows for two things, as you know. It allows us to both capture the intimacy of a character’s sort of inner world, but all the expansiveness with the wide lens of the outer world. And if you frame it right, and you light it right, and the production design with Celine Diano, if you do that right, then you can allow what’s in the lens to unfold. Only then you are informed of what to do next, and that was the approach. It’s just allowing that breath and that movement to be organic, even with the most hilarious parts of the film. Let them play out. Let the actors do and discover what they are doing.

I think we really see that, particularly with Jack, who starts out in the film talking a mile a minute, rapid fire. He’s pulling a con game on everyone, but the deeper he gets into knowing Peel and being a part of his life, his whole temperament, the cadence, it comes down, it slows down, there’s less dialogue for him. He becomes more introspective and observational as opposed to trying to take charge and cover up his own insecurities, and that really shows in the character of Roy.

That’s beautifully, beautifully said and I would agree 100% with you. I think as he finds his place, as he finds who he is, as he finds out what he truly cares about he begins to become a little more still, and the effect that Peel and his stillness on him. He begins to see more. And to your point, he’s a hustler. He knows the streets. He’s a very observant human being just to survive, but it transforms into something different, there’s more of an emotional connection to his observations.

I would be remiss not to ask you about the beautiful scoring. In addition to your needle drops you’ve got scoring that is so beautiful, and it comes up as lilting at times with that innocent kind of feel to it, so I’m curious about how you selected your individual needles drops and then working with Kathryn [Kluge] and Kim [Allen Kluge] on the actual score pieces.

Well, Kathryn and Kim, I have to start with them. They, as you know, scored “Silence.” The word maestro, if you will, really fits with these two. They were so connected to the soul of who Peel is and what he represents and what the transformational, almost spiritual element of the film, in terms of that internal journey. They connected so strongly with it, but what they understood was actually a comment you made earlier. You can go sappy with this. It can be heavy-handed on the emotional front. They understood the whimsical element. They understood that to find that balance, and the right use of instrumentation, and the right chords, and the right . . . We had extensive conversations about that balance, right? There had to be sort of the lower tones that grounded the film and the emotional value, and it had to be those higher tones, like even the use of the kalimba, which is a strange thing to do and use for this kind of film, but it worked because it represented that whimsical, pure, almost magical element of Peel, which is there. And they understood that balance so well and got into the fabric musically of who these characters were, of what the themes were, which were two really which were important for music, and both for the songs that we chose and also the score, they had to be of service to the theme. One was the power of innocence to heal. And the other was finding our tribe. Who’s our tribe? It’s not always your blood. It could be who comes along in your path who really understands, supports and sees you. And it also to be fun, it had to be light in much of this because if we got heavy-handed, to your point, I think the trap of melodrama could set in.

It’s been a while since you’ve done a narrative feature as a director, Rafael. So I’m curious, what did you learn about yourself making PEEL that you can now take forward, be it personally or as a director, into your future projects?

What a great question, Debbie. That’s a deep, deep question. But I can say this. One of the things I learned from myself in this project was that sort of the challenges of selling a story, making a film on a tight budget and the days, and this speaks to the character. There’s an inherent truth in your ability to be still and to listen, and I think in terms of listening to crew and the department heads, whether it was the DP or all the department heads, so listen to the actors and guide them and guide myself in finding what we were looking for, to listen to the producing partners, and to be still in the midst of chaos or discomfort. And that’s one thing that I learned through this process that then allows that stillness and that ability to listen and engage and be present. I think that allows for stories to truly unfold, take off, express themselves, and find themselves. You’re sort of orchestrating something that’s beyond you. That’s what I learned, I think, as a director. And I think it’s different from my first film that I was trying to do that, but I believe here I found that ability to trust both myself and trust my collaborators, and the story itself.

by debbie elias, exclusive interview 05/03/2019