Almost 15 years ago, production designer RUTH DE JONG came to light thanks to Los Angeles Film Festival and “Swedish Auto”, a small independent film from first-time writer/director Derek Sieg and starring Lukas Haas and a still relatively unknown January Jones. Six years later, De Jong’s craftsmanship amazed and, together with wardrobe, set the entire tone of Jared Moshe’s quietly exquisite frontier western “Dead Man’s Burden”, which also made its debut at Los Angeles Film Festival. To see De Jong’s design talent and visionary eye develop over that time span was eye-opening as to her ability to use production design as an integral storytelling tool and to create an immersive world for the actors and audiences alike. Others also took note of her work as it wasn’t long before De Jong production designed Kenneth Lonergan’s feature film, “Manchester-By-the-Sea, starring Casey Affleck and Michelle Williams. Through her company, De Jong & Co, she designed all of the custom furnishings outfitting the old warehouse residing at the corner of 5th Ave. N and Taylor St. in Germantown. Not only was the overall production design on “Manchester-By-the-Sea” telling as to the specific world inhabited by the characters, but the individuality of each of their lives. And then De Jong made the jump to television with David Lynch’s redux of his acclaimed series, “Twin Peaks”.

Staying within the television genre, Ruth de Jong now finds herself as production designer for Taylor Sheridan’s YELLOWSTONE. Despite its episodic format, YELLOWSTONE has all the hallmarks of a feature film both in its scope and in Sheridan’s approach to filmmaking. Along with that of costume designer Ruth Carter and cinematographer Ben Richardson, Ruth De Jong’s production design is integral to creating and establishing the visual and emotional texture and continuity of the series, not only for Season One, but in laying the foundations as the work is handed off to a new crew of master artisans for Season Two.

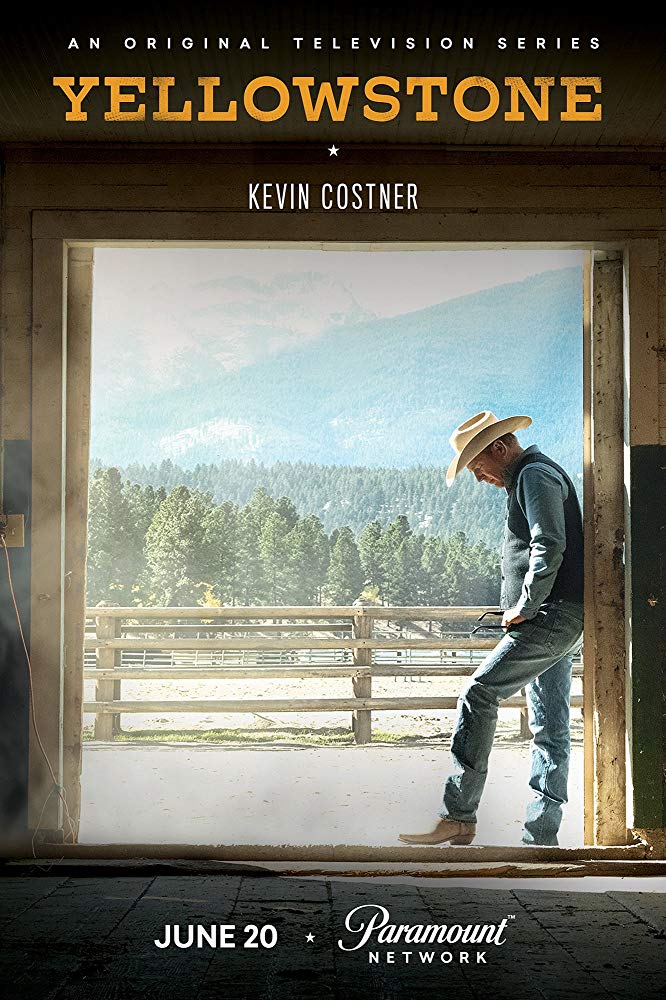

Starring Oscar and Emmy award winner Kevin Costner, YELLOWSTONE boasts an exemplary ensemble cast in this modern western that retains the mores and touchstones of the Old West which are such a recognizable part of the tapestry that is America. Costner, as John Dutton is a sixth-generation homesteader and patriarch of a powerful, complicated family of ranchers. The Dutton ranch is the largest contiguous ranch in the United States but suffers from the conflicts arising from its borders – an Indian reservation, America’s first national park, and an expanding local town complete with land grabbers and corrupt politicians. In addition to Costner, other principal cast members adding to the fabric of YELLOWSTONE are Luke Grimes, Kelly Reilly, Wes Bentley, Cole Hauser, Kelsey Asbille, Brecken Merrill, Jefferson White, Danny Huston, and most notably, Gil Birmingham.

Affable, outgoing and with a wonderful sense of humor, in speaking at length with RUTH DE JONG, her passion and commitment for YELLOWSTONE is beyond evident, as is her conviction to “doing it right” and pushing the envelope as far as possible by not giving in on quality or design choices that impact the overall story and characters or the quality of its telling. Describing this as “physically the hardest production” she’s ever experienced with “an insane amount” of labor, the proof of her labors is in the pudding. As Ruth reflects on her journey in creating YELLOWSTONE, one can almost hear the pain in her voice as she relates instances where she was forced to compromise on her vision for various aspects of the production. But as she now realizes, thanks to YELLOWSTONE, she knows there’s nothing she can’t do. She challenged her own skillset and succeeded one hundredfold in making Ogden, Utah, a living and breathing substitute for Montana, steeped in authenticity, from trailers trucked in for the Native American community to interior sets built on a stage right down to actually milling logs for the build-outs. However, the crown jewel of De Jong’s production design for YELLOWSTONE is the Dutton ranch itself. After an exhaustive search, De Jong found the Chief Joseph Ranch in Montana. A perfect find and a perfect fit both for the series and for Costner’s character of John Dutton, this was something on which De Jong would not compromise. One look at YELLOWSTONE and the Dutton ranch is all it takes to understand and appreciate Ruth De Jong’s tenacity for perfection and her love for the beauty and generational texture of this world she helped create.

Beautiful work, Ruth. Absolutely beautiful! What a journey since we first met at LAFF on “Swedish Auto” and then again with “Dead Man’s Burden”! Seeing what you did with “Dead Man’s Burden”, a period western, it doesn’t surprise me that you were tapped by Taylor Sheridan for YELLOWSTONE. How did you come to YELLOWSTONE?

Taylor came through my agent. Taylor had called my agent looking for recommendations, and so that was literally how it came about. Taylor called me and said, “We’ve got to do this.” There was no, “Would you like to” or “need”. It was, “You’re doing this,” which was very flattering. Obviously, I have a big heart for the west, and the opportunity to do a modern western was very exciting and to be in Montana and in a part of the country that personally has always been very special to me. Then you actually get to go work there in Montana which, not a lot is shot up there. It’s sort of new territory. So I jumped in very quickly, and that was how it all started in the beginning.

I know that the Dutton Ranch is shot at the Chief Joseph Ranch in Montana, so that’s pretty much established, but I’m curious how you then go in and tweak that and then create the production design to create this world of John Dutton. His children splinter out, and then you’ve got the Native American world of Gil Birmingham’s character, and then Danny Houston’s character. We get the politics, we get the land grabbers, we get the Native Americans, everything is so distinctly different but cohesive. And that all falls on you.

It was very interesting. Finding the ranch itself was very, very hard. Kevin Costner, his character John Dutton has this statement that says, “Leverage is knowing if somebody had all the money in the world, this is what they’d buy.” And it’s like, how do you take that and how does a viewer believe that meaning no matter what. It was very daunting to say, “I’ve got to find something that’s beyond epic that the scale is correct. The period is correct. It’s just the story.” I worked with Taylor a lot on this. Who is this family? How long have they been there? Why did they settle there? And then dealing with what he wrote about how the ranch is in constant conflict with its borders; the town is expanding, the reservation, the national park. How do you encompass all of that in a two second “here you see it, there you see it” and have someone actually believe that it’s authentic, it’s justifiable, it’s expansive, it’s a big sky. And we were based in Utah and I was like, “I’m not finding this ranch in Utah.” The studio, for incentives, wanted me to find it there. I just got on a plane. I went to Montana for two weeks with our supervising location manager, Charles Skinner, and I was like, “We’ve got to find this!” Taylor wrote the script in Livingston and it’s supposed to be the largest contiguous ranch that borders Yellowstone, which is completely fictitious. But I was like, “It’s got to be that landscape. There is no landscape that duplicates Paradise Valley.” [Looking] high and low, we couldn’t find a ranch that was fitting in Livingston. They were incredible and the landscapes were incredible, but the houses were either modernized or just not grand enough.

We went to the film commission. I said, “Give me every single historic ranch in this entire state,” and I just went through files, and we stumbled across Chief Joseph. It was in the Bitterroot Valley, which is four hours on the other side of the state. And I was like, “We’ve got to go see this.” We jumped in the car one morning. We were in Livingston staying in hotels in Bozeman. It was just myself. And the studio the whole time is screaming at me, “Come back to Utah. We’re not going to support you there!” And I was like, “Taylor, just give me a few more days. Give me another week. I will find this.” And so it was one of those, “They’re going to fire me. This is crazy.” But I drove to Chief Joseph, cold called, pushed the gate button on the code. Had no idea if a corporation owned it, if it was a single family who was there. They graciously opened it. It was privately owned by a family, and we explained what we were doing. [The owner] was very hesitant like, “Sure, you can look at it, but. . .” It fit the bill across the board, beginning with when it was built and the whole story of that ranch. The Bitterroot is a very closed valley. It’s not expansive, but this specific ranch just happened to have a gap and an opening and it had the big sky, and it had the rolling fields as you saw, and it had the trees set off. This is it. We used the great room in that ranch and we used all the barns. I completely rebuilt all the corral systems from scratch.

The white barns were there. We added the Y for YELLOWSTONE, but then we tore down every fence and rebuilt all of that. All the bedroom sets we did on stage, but in the ILK, I found a company in Montana that dealt with all real logs. We milled everything. I did it in a very traditional way as fast as I could, which is not the studio way, but that’s just the way I work, and my construction team was incredible. So they came down to Utah, this log cabin company. John Dutton’s bedroom, Beth’s bedroom, Jamie’s bedroom – all of those you think are in the house, but they’re not. They’re onstage. The great room, which is the massive living room, we shot practically at the ranch, inside. We just tried to mirror that same aesthetic in all the other rooms.

I have to say, I want John Dutton’s bedroom for me. I love that bedroom.

[laughing] It was a lot of fun. It was just so much fun to create and to put together and just dive into this, into a modern day western, honestly. It’s ow people truly live today and trying to keep it grounded and practical, but yet as over the top is John Dutton is, I just kept striving for believability. I hope that was executed. You never know if someone’s like, “Uh . . . .”

Looking at the ranch, looking at the interiors that you built on the sound stages, you feel the six generations, you feel the history of the Dutton family in that house, and you definitely feel the authenticity. It is absolutely amazing. And to know that you rebuilt all the corrals. Those are some nice corrals out there. Let me tell ya.

Those cost a pretty penny. [laughing] But it was worth it, and they needed to be because we had real livestock, the cattle, the buffalo, the horses. The corrals were all kind of falling apart. Everything was leaning, everything was rotted and it needed to be a working ranch both for our shooting purposes, but also just for you to believe. This guy [Dutton] is not running a janky operation.

Yes. If he’s that rich and has the biggest contiguous ranch anywhere, we need to know that he has the money to do this, and it definitely comes across. But then you have to go and you’ve got to work on a town, and you have to work on a reservation, and you have to capture Jamie’s whole world, that legal world, the political world. And that, while you retain a lot of the earthy feel and the wood tones, that you really contemporize.

And that we built from scratch. We found a piece of land in Utah that we excavated roads into it, and it was literally a sagebrush landscape. So the reservation that you saw in the pilot when you come in, the car comes in, all those roads we excavated and then we plopped down each trailer and corrals and gardens and all the layers of the junk in the old cars and all of that. So that we just built from the ground up. We bought the trailers from trailer lots in Montana and shipped them. I think each trailer was a couple of grand and then we shipped them on wide loads and plopped them down there.

Your shipping might have cost more than the trailers!

I know. It probably did.

Here you are creating this world, this landscape for this wealthy, wealthy family where money is no object, but money had to be an object for you to create this world. Where did you have to pull back from your vision, not even Taylor’s vision, but your vision? Was there anywhere where you had to sacrifice something? Because the production company doesn’t have the same value as John Dutton?

Definitely. I think where I felt I personally had to sacrifice was not getting to shoot this in its entirety in Montana and not getting to shoot as much as I wanted in Bozeman and in Livingston and in the park. All of that I pushed. I had to push. They were like, “Fine, you can have your ranch in Montana and that’s it. And everything else you have to duplicate in Utah. So you have to find a downtown Bozeman in Utah. And we found that in Ogden. . . There are so many little things that make me cringe, but it was the closest match. And I knew the ranch had to be there. I was just not going to give that one up. So I basically said, “Fine, I will give you everything in Utah, including the Indian reservation,” which should have been in Montana. It was sort of written up after the Crow Reservation. And unless someone did some extensive research, there are subtle differences within the topography and landscape of Utah and Montana. There just are. But I felt we cheated it as best we could. We had over 275, 85 sets. It was bonkers. You think of all the little restaurants and every place they were meeting and all the clubs, all of that we just had to find and dress and create. The modern club where the golf course and everything is, that was all Utah, and where he rides up on the horse? That was really important to me cause it’s like, “Well, this is supposed to show this is infiltrating his [ranch], it’s coming close to his property.” But it was in sagebrush country in Utah, and I was cringing because I’m like, “This just looks flat.” We just scoured high and low and I was very picky. But that’s, to me, where I sacrificed was having to do all this stuff in Utah that I was not thrilled about. But we did it.

Well, you worked absolute miracles, Ruth. There is not a moment where I didn’t think that this wasn’t all in Montana. I knew it wasn’t all in Montana, but it definitely looked like it was all in Montana. And that’s a testament to you and your skill set and what your crew did.

Thank you. We definitely painstakingly scoured. This is just not one we took lightly. We felt like at any minute it could pull you out of the story if it was just a bit off. TV is hard because they move at such a fast pace, they give you no time to build. I had my crew on seven days for six weeks straight, which I’ve never in my career. It was just bonkers where they’re like, “Nope, this is the time you have. You got to get it done.” So it’s been that thing of, “Well, I don’t want to compromise the look, so you have to approve over time.” It was a dogfight the whole time. But it was worth it. . . It just mattered to me how authentic my work was. And the rest I just had to leave up to Taylor and actors. I just knew I wanted to take it to the Nth degree until someone would be like, “Nope, you’re done.” But then I kept getting away with it somehow! It was worth it. I’m very budget conscious, but there’s ways where it’s easy to just cave and be like, “Okay, fine.” But I knew we’d end with some McMansion in Utah if I did that with the ranch. You wouldn’t believe it.

Does it help, because of the authenticity that you wanted and that this show needs, does it help having someone like Kevin Costner in the leading role because of his quest for authenticity like when did “Dances With Wolves”? It’s well known that he is a stickler for things like that. Does that help someone like you when you’re going for authenticity that you have a lead actor who is known for being hell-bent on that himself?

Yes. I experienced that same thing with Casey Affleck and “Manchester-By-The-Sea.” He was also someone who’s incredibly authentic and allowed that vision to trump any argument or money or you name it. It’s ultimately like, “No. For this work, dah, dah, dah, dah, dah. . .” And Kevin was the same way. When he got to that ranch, he was so supportive, which was so helpful. Just championing the work the art department was doing and myself and he was blown away. When he got to that ranch, he was like “Yes!”. And I think it helps all the actors just go to a place they otherwise might not have gone to because they’re like, “Oh, I don’t really believe it, but I’ll act and I’ll figure it out.” I never want an actor to show up and go, “Oh, this is not what I imagined.” That to me is I’ve failed. So he was over the moon. Taylor brought him up early on and he was just like, “Yes, yes, yes!” And then that helped with how many days we fought for to be able to shoot up there. . .We’d get to go three, four weeks versus you have eight days up there. I let Taylor and Kevin fight those battles, and it was great because they wanted to be there.

When you’ve got Kevin Costner Costner willing to fight the battle for you, that’s when you step back and say, “Go ahead, Kevin!”. The cast for this show, not just the core ensemble, but the hundreds of people, the character actors, the supporting players and all, many of them have never done a western before. And this is a western. It has all the core elements of a John Ford picture. You’re dealing with the livestock, dealing with Mother Nature, dealing with the territories. This is a western in the truest sense of the word. It just happens to be happening now. So it had to be so extremely beneficial for all of these actors to actually feel and be in time and space as it should be.

Definitely. That’s so important to me. We’re months ahead of them showing up and if they show up and are underwhelmed, that’s my biggest fear. It’s like I’ve failed them. Everybody just wanted to be in Montana all the time on that ranch and it put everybody in situ and in the mindset. Even all the crew even was like, “We get to work here?” Sure, there were so many times that we were up against time and they’re like, “Just green screen. Kevin can pretend he’s on the porch,” and we were all like, “No, it’s going to affect all aspects of your production. If you’re interested in shooting this kind of epic on green screen, you can find a new designer. That’s not my deal.”

And we all know Kevin Costner would not want to shoot something like this with green screen.

No. It’s looking out at the mountains, it’s looking at the big open spaces. It’s the whole deal. And you get that, and I think we also achieved that. And coming back to the stage, that’s where I painstakingly fought for the sets to be authentic on stage and just demanded them to push and change the schedule around so we had more time to get the stage sets correct and right and fitting with what we were shooting in Montana. The bunkhouse we built from scratch as well. That was on stage. The governor’s office was on stage. Kevin’s office where he goes to the livestock commission, that was on stage, and they were all supposed to be all these little sets in and around Livingston and Bozeman, and we just tried to obviously do it justice as best we could on stage, and I think it worked.

How much time did you spend doing research before you even started construction and getting into set dress once you had that done because of your attention to detail?

I wish I could say I had all the time I wanted. I had to simultaneously do both. So I brought on a team and I had people researching as we were also picking the ranch, as we were also saying, “Okay the set designers need to start drawing.” So it all ended up time was not on our side on this production whatsoever. It was brutal. It was physically the hardest production I’ve ever experienced with just having no time, no life, working around the clock. We had an army to pull it off in one. I barely had two months before we started shooting. It was so fast, which is not, not, not normal. A normal film, I’ve got eight to twelve weeks of prep alone before we even think about shooting. We were on top of each other. So the very first thing I had to get ready was the ranch, and we did that in nine days, think total. I think we immediately gutted the corrals and dressed the great room and did all that and just threw labor at it, an insane amount of labor. It was just bonkers.

How long did it take with the set dressing, because there are so many pieces in there that look antique, that look like they have been in the family for generations?

They are all antique. The set decorator was Carla Curry. She’s fantastic. She personally lives on a ranch in Texas. You can look up her work. She did “Walk the Line.” She’s done some great pieces, and I knew picking her, there would already be an unspoken dialogue. We could just jump five steps ahead, ’cause she knew. Her husband is actually a cattle rancher in real life, so she was already there mentally. I did a lot of mood boards and then we had a lot of dialogue and then she went shopping with a bunch of shoppers. A lot of stuff. There’s a fantastic rental house in Los Angeles, Omega, and they have been collecting for years, and we raided their period collection of just American antiques and European antiques. And we sent trucks out, just sent them to the ranch. She also did a lot of antiquing in and around the state of Montana and Utah in the west and just got some incredible pieces. Everybody just hit the ground running. We didn’t have time to really build or create any furniture from scratch, which we often do when we have that time. But we didn’t need to. It was very important to us there was a lot of European antiques, assuming his [Dutton’s] family migrated over and settled there and began ranching there. We had that logline going with Taylor, but then also adapting Native American rugs and pottery and baskets, just different subtle things that they would have collected over the years living in that region. A lot of the drapery was Ralph Lauren. A lot of that stuff we just kept as authentic as possible and very Americana and very true to character. It’s subtly ostentatious if you know what I mean. It’s not in your face, over the top. It’s more just the leather sofas and the plushness of it. But it’s also very grounded in “this is an everyday working ranch where he holds court.”

We’ve got season two coming up starting in June. I have been told there are new characters and some explosive things happening. Have you had to now create more design for season two?

I did not design season two actually. I went on and did a different film; Actually Jordan Peele’s “Us” which just came out. So they brought on a designer for season two in its entirety who picked up where we left off.

So you did all the hard work? [laughing].

Exactly. [laughing]

Ruth, I’m curious. You always take something away from a project when you work on it. You learn something about yourself, you take something away. What did you take away from the experience of working on YELLOWSTONE that you will take forward into future work as a production designer?

I think for me it was that I’ve never worked with such little time constraints. Like I said, money was not necessarily a massive factor, because we had no time, so we needed something, and that was either give me labor and give me a budget if you’re not going to give me any time. And I think going forward, nothing scares me after that project. I would say the scale of that, the amount of set, the time constraints, I think I left those however many months I was on it for, and said, “There’s nothing that scares me. I know anything’s possible if you give me – – And if you’re not going to give me money, then I just need a little bit of time.” I realized that triangle of how to just pull something off. And I don’t know that I ever did that before, because I’ve always worked on much smaller scales. It was also I liked having to figure out how to work in two states, run multiple crews, logistically be organized and say, “Oh, I can do this, this is doable. I know how to …” There’s those films you hear about that shoot all over the world and you’re thinking, “How do they do that?” Now it’s like, “Oh, I know how to do that.” That was a distant mountain to climb and go, “Okay, I got this.” We poured our heart out, our whole team, and I had such a fabulous team, fabulous supervising art director. Call me crazy, but I do it all over again. As torturous as some of those days were, it was a special one to be a part of and just create the American West, and its contemporary. It was just great to be out there and be shooting in the element. It’s always nice.

by debbie elias, exclusive interview 04/03/2019