Toronto-born cinematographer JONATHAN FREEMAN is perhaps best known for his award-winning work on the small screen with Game of Thrones and Boardwalk Empire, as well as Homelend Security and Rome, but he is equally adept with theatrical films such as Remember Me, Fifty Dead Men Walking, and Hollywoodland. Yet, it’s something about the small screen that keeps calling to him and does so again with DEFENDING JACOB.

A three-time Emmy winner for Outstanding Cinematography for a Single-Camera Series (One Hour) for his work on Game of Thrones and Boardwalk Empire, cinematographer JONATHAN FREEMAN now adds another Emmy nomination to his credit, this time for Outstanding Cinematography for a Limited Series or Movie for the acclaimed eight-episode mini-series DEFENDING JACOB on AppleTV.

Starring Chris Evans, Jaeden Martell, and Michelle Dockery, DEFENDING JACOB is based upon the acclaimed novel by William Landay and adapted for this limited series by creator/writer Mark Bomback. Directed by Morten Tyldum (The Imitation Game), DEFENDING JACOB is the story of the Barber family – successful Assistant District Attorney Andy, wife Laurie, and 14-year old son Jacob. They are living the dream as the ideal American family in a small Massachuetts suburb. Their happiness and success feels as if Teflon-coated; that nothing can destroy their lives. But that world is shattered when Jacob is charged with the murder of a fellow student. Forced to sit on the legal sidelines, all Andy can do is believe in his son’s innocence. But what happens as evidence mounts, indisputable facts are discovered, and doubt grows as to Jacob’s veracity and we watch the Barbers go down the rabbit hole of crisis as their once idyllic world starts to crumble piece by piece.

Collaborating with Tyldum on all eight episodes of the series, the pair made a plan and stuck with it, developing a specific visual tonal bandwidth built upon lighting and lensing, starting with anamorphic lenses and LED lighting and then honing in on the use of close-ups as the critical element of this storytelling, finding that “sweet spot” of camera position to draw the viewer into the character and the story through the “windows to the soul” and shooting with multiple cameras strategically positioned, all fueling the metaphoric ambiguity that drives the story forward. The result is captivating and compelling.

Following his Emmy nomination for Outstanding Cinematography for a Limited Series or Movie for his work on DEFENDING JACOB, I spoke at length with Freeman about his cinematographic approach to storytelling with the series. Humble and passionate, Freeman presents with an infectious and decisive calm, something that would be welcome to any production, but works particularly well here.

I am a such huge admirer of your work, Jonathan, so it’s very nice to finally meet you and get to chat with you now about DEFENDING JACOB. Boy, oh boy! Your lighting and your lensing with the density of detail in the shadows created such a metaphoric ambiguity throughout this series so that visually, it spoke volumes and just sent the mind reeling, especially for those people that were not familiar with Landay’s book and did not know this work. The entire look of the film is spectacular, Jonathan. The first thing that strikes me is this great collaboration between you and Morten [Tyldum]. How beneficial is it for you as a cinematographer to be working with the same director for this entire series rather than having directors bounce in and out?

The key thing with this experience is that it’s a lot of work, but the benefit is that essentially it’s as if you’re shooting it yourself a little bit. You have a complete arc that you are completing from the very beginning to all the way through the middle and to the end and you’re doing it with one director who has one vision. As I said, it’s a lot of work, but there are great benefits to it. Of course, eventually, you develop a shorthand which hopefully will make filming more efficient and keep a consistency throughout it.

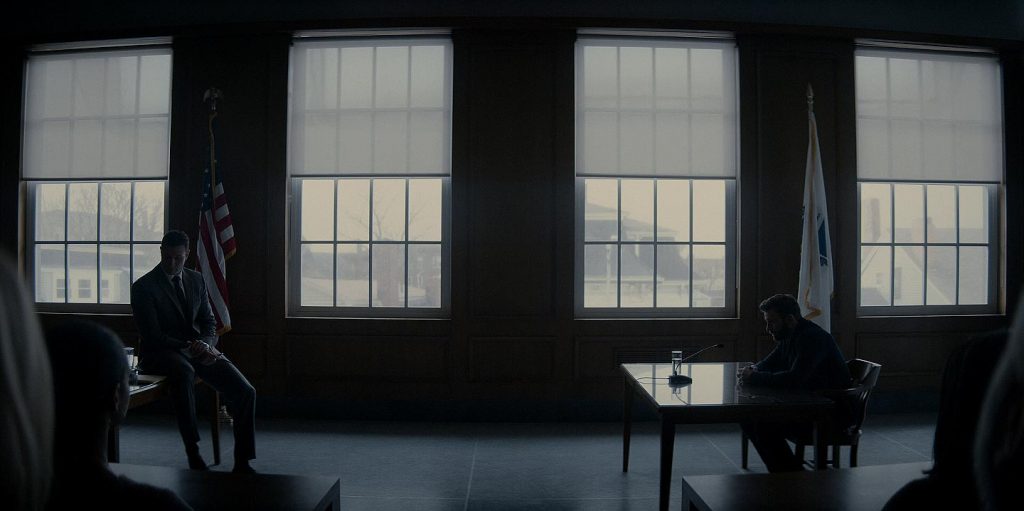

Something that really helps drive DEFENDING JACOB home is the camera positioning and the use of closeups, particularly ECUs. We’ve got a lot of ECUs in this show, none of which are extraneous or gratuitous. Each one has a point of view and the lensing is so perfect. With your framing and your camera positioning, Jonathan, we are in the eye line of each individual person, depending on whose POV it is, with the exception of Jaeden’s character of Jacob. The camera is typically more aloof when it comes to him and there is more distance as we are stepping back from the character of Jacob, making us think either, “Okay, he’s a kid. Hands-off” or because we’re scared to death of what we’re really going to find out about him. But it’s the intensity and that direct eye line that just drives the series, especially with Chris Evans. Those courtroom scenes? Wow! So I’m curious about your camera positioning, the decision to go that route, to bring that intensity and immersion to this story.

You’ve articulated better than I have ever had, but I will say that it’s interesting. When I first joined the project, Morten sent me the first five scripts, they were the ones that were available at the time, and Mark Bomback’s writing! I hadn’t read the book, so it was all fresh to me, but his writing was so intriguing that I was sucked into experiences of all these characters then, and when Morten and I sat down, as we went scene to scene chronologically, we really got a strong sense that what was really important was for the audience to try and experience the story through the protagonist’s eyes, if you will. Morten, particularly, wanted to lean in towards that. But also as you very beautifully pointed out, we wanted to start to create an enigma around Jacob. The concept was to intentionally shoot Jacob more objectively as time progressed and we started to question whether he is guilty or innocent. So the lensing was very, very conscious to be subconscious in that sense. Also, we knew that we had these fantastic, amazing actors and that most of the drama was actually going to take place on the landscape of their close-ups.

Two things came out of that. One is that the use of close-ups would be not just a motif, but a critical element in terms of our storytelling and, that the choice of glass to shoot those close-ups was paramount for us. So one of the things we decided early on was to shoot anamorphic lenses partially because of the bokeh, which is essentially the out-of-focus blur of a lens. With anamorphic, of course, that had a much more distorted perspective and somehow that felt right for us in terms of capturing these close-ups. Also, the quality of the optics that we were able to get with that, we shot with the Panavision G series, was very helpful in putting it together for us. It has a very cinematic quality as well to it. I wouldn’t say that the equipment actually led to choices of the shot design, but it reconfirmed that this was the right approach, so it was really important for us to be able to find those moments where we could hit on those close-ups and just let the audience be drawn in by the performance.

It is absolutely magical. And I love that you went with the anamorphics because it really does give this a cinematic texture, and also allows us to feel the grittiness of the crime at hand, the unfolding mystery. You’ve got a dead body. A kid. You expect a kind of grit to come in and the anamorphics really fulfill that. I love your choice with that. I’m curious, Jonathan, how close were you able to get the cameras to your subjects, to the actors for these close-ups, especially the eyes.

Again, the one motif we developed, and it’s nothing revolutionary, but we felt like there was a specific angle which we used for all the characters that we could at given points; an angle where the camera would be a few inches higher than the eye line and usually somewhat three quarters [on the face]. So it’s not directly connected with the eyes. There’s something not odd about it, but there’s something that feels disconnected in some way. By doing that, we felt that it almost has the effect that you are really kind of leaning in, like a therapist’s perspective, because it feels more intimate than a standard close-up. And again, it’s something that it doesn’t really make any sense, but for some reason it worked for us on this project. Obviously performances were key and Morten and I both agreed that we would need to have as many cameras running as possible just to capture performance.

But the challenge is always, the more cameras you put up, the more sacrifice that you make for each angle, so we did come up with this camera positioning slightly above the eye line. It was one angle that was sort of a perfect B camera opportunity, whereas we could shoot a more standard close-up coverage and at the same time capture this very critical intimate close-up, which the editors could then choose as to when they used it or not. We shot a lot of material and a lot of angles, particularly in the courtroom, but it was our editors [Tanya Swerling and Tom Wilson] who really, really helped put it together. I don’t think there’s enough credit to our editors in the sense of storytelling that was involved because we gave them a lot of material, but the choice as to when to use certain shot and to build the sequence, to get to a climax, was skillfully done by both editors. The one idea that was really emphasized well, which I felt was appropriate, is that there is not a lot of camera movement in the courtroom. But just by the nature of having multiple angles and not necessarily repeating those angles in the cut, you start from one perspective and then you literally move around the scene in the cut, giving it a much more dynamic and intense feeling than if it was a standard coverage or edited conventionally.

I have to compliment you immensely on the courtroom scenes and your camera angles. I was in law and in courtrooms for over 27 years, so I know the look and the feel from various perspectives in both civil and criminal matters, and you really nailed it with the camera angles, the multiplicity of camera angles from multiple cameras. We feel the tension. We feel the ambiguity for the majority of the episodes. We’re feeling that Chris Evans’ character, Andy, is the one on trial. And we wonder, what did Andy do? And that comes from the way the camera gets down when Chris is leaning down onto the witness table and he’s being grilled. The camera is right there. There’s no movement of the camera and we’re just with the character. That infuses so much into the overall story and also for the audience watching. So beautifully done, Jonathan, beautifully done. Editing does an immense job, but it starts with you getting those angles. It’s just so authentic with real nail-biting moments. Hats off to you on that one.

Thank you, Debbie. I appreciate it. And your observations are spot on. Like I said, you articulate what we’re trying to do better than I ever could. It was kind of an unusual experience in that usually when you sit down, you talk about ideas and concepts and motifs. Those are things that you try and utilize when you can, but more often than not, you just take them out once in a while and apply them. Morten was really enthusiastic about sticking to the plan and we did. We actually were able to encourage our operators and even our actors with this approach. This is one of the few projects where we had a plan from the very beginning and we stuck with it. And I think in the end it was successful in that we did what we had set out to do. So in that sense, I was really, really satisfied. That’s the one thing that I guess I’m most proud of.

The lighting is such a key element here, but for the bulk of the series, it’s very denatured and as we go along and the puzzle pieces unfold and more is revealed, we see the breakdown with your focal length. We see the background breaking down a lot with the lighting, as well as the camera blurring the background to metaphorically represent the family’s life, their world, the Barbers’ world is collapsing. It’s disintegrating into nothing. So much of this falls on your lighting. I’m curious what lighting you were using and in terms of that, your color as it goes hand-in-hand with that; so your lighting and then your LUTs to get the density of that denatured look.

With the overall approach, in some ways, the grand jury room scenes with Chris were sort of the inspiration to this story. Call it the essence or the tone, it’s almost like a requiem. So the obvious choice of being sort of somber winter for that essence made sense to both Morten and I. We referenced a lot of films that had that tone, Morten certainly having worked on a few others. But there was something about that tone that we wanted to emulate. It was a fine balance because it’s an appropriate tone, but you also don’t want it to be so heavy-handed or so somber that it’s oppressive and/or distracting. What I wanted to do, and that Morten allowed to happen, but not going towards a tone where it was brooding but diverting from the theatrical drama, was controlling the light as much as we could. Take the sun out as much as possible. I was able to control the light from a lighting instrumental. I was utilizing very soft, large sources with a strong fall-off. We still create the mood, but, for example, in the close-ups, it was really important to me to create the mood through the close-ups but at the same time not lose the windows to the soul – the eyes of the actors – which were so critical. So I would play with fall-off a lot, but I would always make sure that we wouldn’t lose that information unless we chose to. More often it’s more cameras and lighting where there’s the shot from the back of someone’s head or from three-quarters back, or denying the audience a sense of where this character is at the moment.

In terms of lighting, this the first project where I used almost exclusively LEDs. For many years I have been using dimmer boards, small dimmer boards, where I have them by my monitor, and I would have my key light, my tow light connected and attached along with one or two other lights that may hit the background or what have you. With tungsten, the challenge was always that you could dim it only to a certain point, but then it would get very warm. So there was always a limit that you had to control that. With LEDs now, of course, the color spectrum is phenomenal, and it only takes one or two punches of a button or turn of a knob and you can shift the color exactly where you want it to be. But on top of that, I was able to fully dim the light up or down. With this setup, I was really able to control light very quickly, “tweak”, if you will, before we actually shot anything and then be able to adjust on the fly as the actors were performing. There’s a lot of hidden fade-in to fade-out with lighting that you won’t necessarily notice unless you were watching for it. I feel this gave confidence to the actors that they could move about in the space that they wanted to and I would have the ability to adjust based on their blocking performance at the moment.

I would be remiss not to bring up the beautiful, colorful, gorgeous work of the vacation sequences in episode eight. A total contrast of what we’ve witnessed up until that point. Those scenes are just beautiful, filled with color, taking advantage of those magic hour moments with the pinks and the oranges. Was there any difference in your approach to lensing that as compared to the rest?

I have to say that it is wonderful being honored with nominations and whatnot for photography, but I feel this is a collective honorary. Those sequences, the Mexico sequences, were actually shot by another photographer, Pal Rokseth. Those sequences were shot at the very end of the schedule and my schedule didn’t work out for me to shoot. He’s a brilliant, brilliant photographer that Morten has worked with in Norway on commercials. So he was able to step into that role. He was also able to shoot some of the material in the Barber house as well where he basically more or less mimics what I had already done. But what I really love is that there’s an opportunity having another photographer shoot that sequence that felt right. It was an appropriate opportunity to completely change the contrast. We followed the sun throughout the house. It essentially wakes up Andy to find the news about the changing fortunes of the family. Starting with that, it was the first time where we introduced sun and that kind of warmth in a long time. And that was intentional. But again, having the opportunity to shoot on location in Mexico and having another cinematographer opening up that world was also a great contribution as well.

But it’s a gyp, Jonathan. You got stuck in cold Boston instead of warm Mexico! This has been a joy talking with you, Jonathan. I love what you do with storytelling and with DEFENDING JACOB light and lens is an essential element of the storytelling. I am so thrilled for your Emmy nomination and will have fingers crossed for you.

Oh, thank you. As I said, the honor is a collective one with a lot of people behind it. I’m very honored by it.

by debbie elias, exclusive interview 08/12/2020