Joshua Caldwell is no stranger to the world of filmmaking and production. For more than 15 years he has produced, directed, scripted, edited, and worked as a cinematographer on everything from short films to features to multiple tv series, even picking up an MTV Award along the way. Now with his latest feature film, NEGATIVE, he dives even deeper into storytelling with a keener visual sensibility, all to a very positive result.

The premise of NEGATIVE is intriguing. We have long seen plots of with characters being “in the wrong place at the wrong time”, but with NEGATIVE, Caldwell and screenwriter Adam Gaines, give us a little twist. Amateur photographer Hollis is shocked and confused when a woman named Natalie appears at his door demanding he turn over a random photograph he had just taken of her while out and about in Los Angeles. Not even finished the developing processing of the photo in his apartment darkroom, Hollis believes this to be some kind of joke; that is until things take a slightly violent turn. Natalie means business and will do anything to get the photo and the negative. Threatening Hollis’ life, she forces him to leave with her, just as gun-toting hitmen are making their way to Hollis’ front door. Just who is Natalie and who are those men? And why is Hollis’ photograph so important? As the pair make their to Phoenix where Natalie claims they will be safe, Hollis slowly puts the puzzle pieces together to find the answers and hopefully, save his own life.

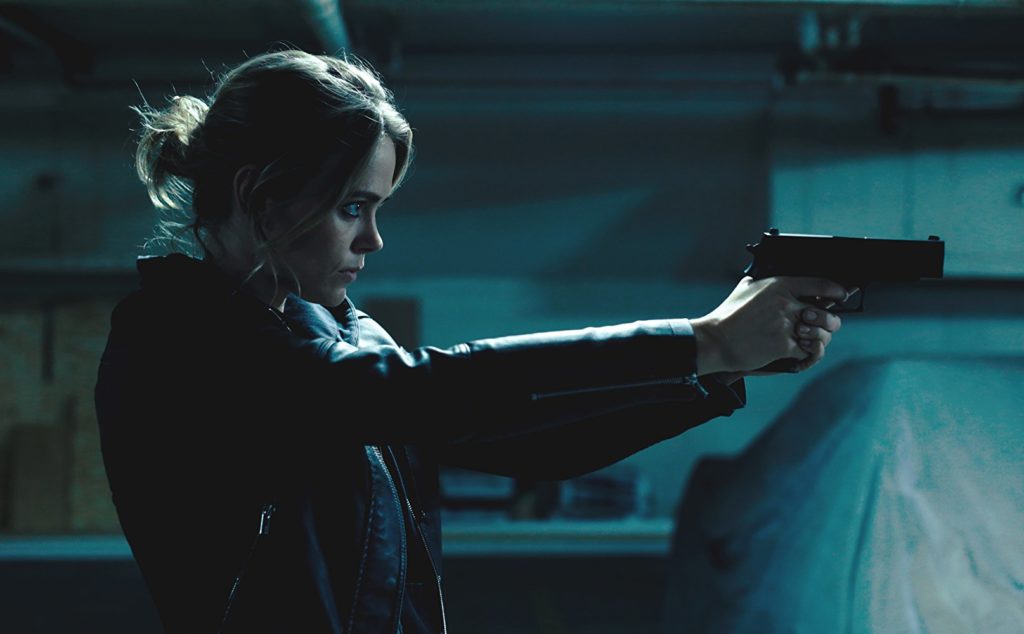

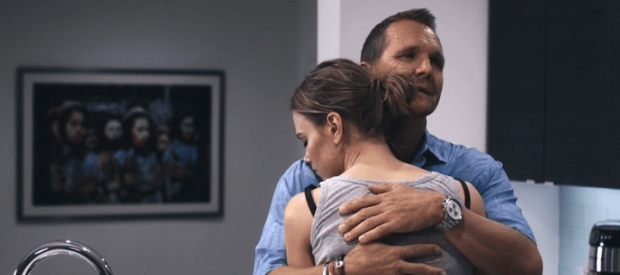

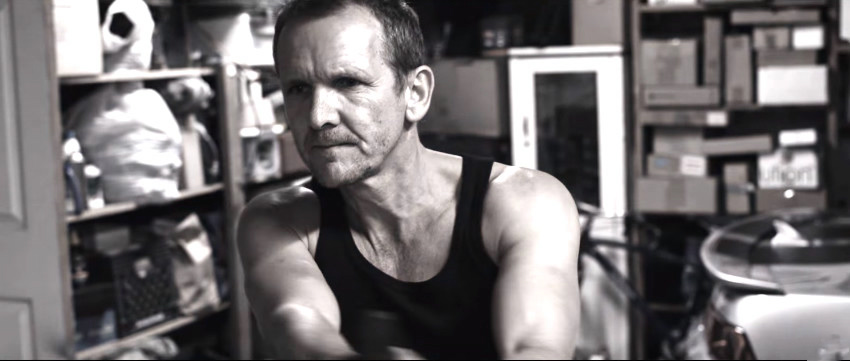

With a cast that boasts Simon Quarterman (“Westworld”) as Hollis, Katia Winter as Natalie and Sebastian Roche (“General Hospital”, “The Man in the High Castle”) as Rodney, the characters prove interesting and ambiguous, and the story even moreso, drawing the audience in as they seek the same answers as Hollis. But elevating the film is Caldwell’s technical proficiency and its impact on the storytelling as a whole.

I had a chance to go in-depth with director/cinematographer/producer Joshua Caldwell in this exclusive interview talking NEGATIVE.

So often you write and direct your own films, but with NEGATIVE, Adam Gaines scripted and you directed. I’m curious then how this project came to you.

I developed it with Adam. Back in college, I had this idea for a short film. A guy goes into Central Park, takes a bunch of photos, goes and gets them developed at a one-hour photo development, and sees this picture of this woman just staring right at him through the picture. And he doesn’t remember taking the photo. I don’t know where it went from there. That was all I had. I had this little beginning and could never figure out what to do with it, so it lay dormant for a number of years. Then a couple years ago I met Adam Gaines. I just really loved how he used dialogue and I really loved his writing, and I said, “You know, I have this idea that’s basically a guy takes a photo of a woman. . .” And I threw out the idea of what if it’s a spy thriller and she’s a spy and she really didn’t want him taking her photo? I also had this idea of, what if you did “It Happened One Night”, but as a thriller and without a romance. So you have these two people that really don’t like each other that are stuck on this journey, and it lasts one or two nights. And that was all I had. I basically took all these things and said to Adam, “Go. Come up with something.” And he did and basically what he came up with is pretty much what we ended up filming.

I love the whole premise. We’ve got a spy whom we find out more about very judiciously with tiny little reveals, bits and pieces of information. You build on that with the clipped dialogue that you give the character of Natalie and how Katia stays in character with that very stoic and steely facial expressiveness and vocal cadence.

Yeah. We had a lot of fun with her. It was really different for Katia, which I think is what excited her about the role. I think that was one of the appealing things about it, playing a character very different than what she had played before. That was also the challenge, right? Because we’re writing a movie that’s fairly dialogue-heavy. You’ve got a character that’s not really talkative, and I thought that Hollis was sort of a perfect foil to that. When we were making this we knew that we couldn’t do a Jason Bourne movie. We just didn’t have the money for the stunts, so I was kind of curious about the idea of taking the aspects of a traditional Jason Bourne movie, like a trip from Los Angeles to Phoenix, but with my idea that it’s at least an eight-hour drive, so what are they going to talk about? What does that look like? It was this idea of sort of the shittier side of being a spy, and that was not all exotic locations and fantastic people and James Bond meeting up with the girl. It’s Natalie, who’s not a social person, is dealing with this guy that’s driving her nuts. And rightfully so because she’s basically kidnapped him in order to save his life. So it became a really interesting sort of storyline. Then in terms of the dialogue, that was one of the things Adam and I talked about. We were kind of interested in making a sort of modern noir. We definitely wanted to push it into a little bit more of a stylized place.

Simon Quarterman and his embodiment of Hollis helps fuel the dialogue-heavy scenes. Hollis deals with the world through a camera lens. He is not a people person. Natalie is also not a people person but is freer with her verbal expression than Hollis. I really like that stilted uncomfortableness that it brings to the film.

That was fun, too, because obviously you’re always looking for conflict of some kind and we just didn’t want it to always be huge conflict. And simply by having two people that don’t know how to get along with each other, it makes for that kind of conflict. It makes for that slightly more entertaining version of it, I think.

And of course, then you give us Sebastian Roche as Rodney. I kept wondering if I was going to see the Sebastian I know so well as Jerry Jacks on “General Hospital” with that double-edged, evil streak in him, particularly when you come up with Rodney making “Fluffernutter”.

That was Adam the whole way. It was also one of the hardest scenes for us to shoot because everyone kept laughing. Adam’s idea at the time was, we’ve just been through all this stuff, we’ve just gotten to Phoenix, and we really wanted to not only challenge the audience’s understanding of this guy that we’re about to meet [Rodney], but also make you feel very sort of comfortable. You’re like, “Okay. We’re here. They’re safe. Maybe something will happen, but they’re safe with this guy because we’re spending ten minutes talking about Fluffernutter. I describe this scene as sort of my little nod to the Cohens in terms of that quirkiness and that weirdness. I really wanted, when people got here and got to this Fluffernutter story just to be going, “What the fuck movie am I watching?” You know? That’s really the response I wanted at that moment to just be sort of really challenged a bit in terms of what you’re watching and why you’re watching it.

For me, watching that sequence and hearing Sebastian Roche talk about Fluffernutter, I’m thinking, “Okay, he’s not playing a Jerry Jacks kind of character. He’s really a nice guy.” But then it all turns on a dime. So that was a win-win for me. We get the quirky humor with the Fluffernutter and then I actually get to see Sebastian turn into the delicious violent and conniving character for which he’s so well known. His “General Hospital” fans will not be disappointed.

Oh, good! Then it worked. That’s what we were trying to do.

I absolutely love the house that you found for Rodney. It is stunning with the white on white and just the cool blue of the pool and the corridors, compounded by the way you moved the camera and Sebastian [Roche] in and out. Because that’s what we see. We don’t see Natalie moving in and out. We see him, Rodney, looking for her. You really made that feel extremely expansive, but it perfectly embraced the whole idea of a spy hunt. Did you make the house look bigger than it really is? And how difficult was it navigating and mapping out that particular sequence so that Will Torbett, your editor, had something to work with to really build that tension?

Originally as scripted it was a two-story house, but it was again very generic, and it was written in a way that we weren’t like, “Oh, we’ve got to find this type of house.” We were looking for something like what kind of house would a retired spy want to live in, especially in Phoenix. The house we used is actually located in Palm Springs, so we shot the house in Palm Springs for Phoenix. But you know, so much of Phoenix is that very Italian sort of villa-esque style, and we really didn’t want to go that way and we thought the other thing is about Phoenix is, it does have a lot of neighborhoods that are very eclectic. So we thought we could get away with something that was more modern, more mid-century. We actually used Airbnb to find the house because Airbnb does such a great job with providing great pictures and easy booking. We reached out to the owner and said, “Would you be comfortable with us shooting a movie there? It’s going to be like four or five people.” And he was like, “Yeah, sure. Sounds great!” So we did the location scout from afar. One of the challenges was we never pre-scouted it. I just knew what it looked like based on pictures. So when we got there we shot that sequence over a weekend. We sort of had to walk through it and say, “Okay, how are we going to deal with this sequence, and where’s the master bedroom going to be and where’s the bathroom where she’s going to shower. How does this play, from where the kitchen is, where are they going to be having dinner?” So we didn’t really create the house as that much bigger than it really is. Maybe sort of cheat the edit a little bit to make it feel like he was walking a little bit more than he was, but in that way, what it really was was just shooting as much as possible, knowing that we could jump cut it if it started to feel too long. But it was about giving Will as much time, as much footage as he could use.

Talk about the whole configuration with the house, such as the closet door, and how it came into play with story design. You’ve got one scene where it looks like one of the doors in the hallway may be slightly open. Is Natalie going to jump out of there? You’ve got another closet door that has the plantation slats on it. Is she hiding behind there and can see what’s happening?

I really wanted to sort of stay with Sebastian’s Rodney not knowing where Natalie was or what was going on, but really staying with him and stay on his point of view without leaving it to figure out where she’s gone or see his literal POV shots or anything like that. I wanted to make it very constrictive in terms of tension. We really just tried to make use of the space as much as possible, but a lot of it was dictated by what was available to us on the day.

Your visuals are beautiful, particularly your desert sunsets which are stunning. And that’s something I always like to see, especially in action films, where you have beauty contrasting the darkness and the violence. Since you were developing this with Adam, how involved were you in the scripting process, in terms of deciding, or getting an idea of what your visuals were going to be? Or did you wait until the script was done, and then take a look at how you were going to design the visual bandwidth?

It’s a good question. When I was developing with Adam, what he would do is sort of send me updates. He would send me an outline and say, “Okay, this is where we’re going to introduce this Rodney character.” And I’d have a full outline and say, “This is great. Maybe change this, maybe adjust this. Go off and write.” Then as he was working on it, I’d sort of feed him stuff in the development parts, like, “Don’t put this all in one place. Here’s what we want to look at. How can we use motels and just generic apartments? How do we sort of write it in a way that isn’t going to push us into a corner on budget?” So I was really focused on that. As it extended to the visuals, was the idea of not limiting ourselves. This was something I did on my first movie, “Layover”, by shooting all over LA. Despite a very limited budget, what I really wanted to do for this was really push. Push the amount of locations, push the actual locations themselves to really give us a scope and a scale that a movie of this budget doesn’t usually give you. But then what happened was that I had certain things in my head. I had the opening with Natalie in the restaurant in my head, and I had some of the motel stuff and a lot of the desert stuff. Then one thing we did was, early on in the process – we started shooting in October 2016 so in June 2016 – we actually went out and did a little test shoot and shot a little short version of basically the scene where he gets out of the car in the desert and she sort of confronts him with the gun and says, “This is what’s going on.” We shot a version of that and I was able to use a specific look and color time it to how I wanted it and how I thought it might look, and then ended up discovering the visual approach to it. Then a lot of it came out of just not only using the color palette that we decided on from a camera perspective from using the Lutz that we had, but also from the locations themselves and from basically approaching it like, “We’re not going to have a lot of control. We’re going to be going to those locations with mixed lighting, with imperfect lighting, with different color temperatures, and we’re going to try to embrace that as much as we can.”

How did you and Will Torbett go about editing this film in order to maintain a flow, maintain the uncomfortable exchanges between Hollis and Natalie, and build us up to that third act?

Will and I’s relationship is great. He started out working as an assistant editor for me, and I’ve got a history of always pretty much ending up editing all of my own stuff. Because I never had the money to pay an editor to edit it, and I could never find an editor that was better at doing it for the price that I would do it for, which was free. So I ended up just having a lot of experience editing all the stuff I was shooting. As a result, I tend to, when I shoot and even when I’m directing, but I’m not also EPing, I tend to have an eye towards the edit. When I’m editing, it usually that means I know how I’m getting into a scene, I know how I’m getting out of the scene, I’ll leave it open in the middle to play with some stuff, but usually there’s only one way that my stuff can go together in a way that works, because I bounce around as I shoot. I shoot long takes, and I do a lot of movement, so it’s about really finding the right frames to cut on.

So what I’ve done now with Will on a couple projects is, basically I finish shooting the movie, or as we’re shooting I’m giving him the footage and he’s starting the assembly. I hate doing the assemblies. I have no interest in them. I’d rather have somebody else do it because I also think that I’m interested in the collaborative part of it, which is, “What is Will going to see in this footage?” I know what I’m trying to do, but maybe there’s a different way to do it, and maybe doing something differently is going to create a new idea in my own head that I didn’t have before. I like to see the first couple of cuts through his eyes, and then eventually I take over, and I actually go through the movie and do passes on everything and get it down to the frame on where I think we need to be cutting. I really pay attention at that point to rhythm, the pacing. I think it’s so important because I’ve just had experiences with other editors where I didn’t have that level of control, and you see where the cuts don’t work. You see where it’s not quite right or you see where the pace gets off because of where the cuts are happening, so I really go in there in a very minutia of the edit to really make sure that everything is flowing well.

Part of it, too, was just based on the story and based on what the script was telling me, we were going to have this somewhat, not languid, but somewhat easy first two acts. Then as soon as we got to the third act, it was going to be ramping up on the violence, ramping up on the intensity, ramping up on what we were doing visually on the amount of cutting we were doing, on the types of sequences we were doing. That really dictated to us. We’re really taking the point of view of these characters, and probably more so Hollis’ point of view; sort of the smoothness of this and the simplicity of this, and it’s not too intense, and it’s not too crazy. Then as soon as you get into that third act, everything changes in terms of the visuals, in terms of the edit, in terms of the music, in terms of everything happening to them. Things get crazier and more chaotic and less straightforward and a lot more confusing.

What were your considerations when working with Bill Brown on the music?

Bill and I go way back. We’ve done five projects together and this was an interesting challenge. I’m usually pretty good at finding temp music that says something about what I want to do, even if it’s not exact. But on this movie I just could not find anything that worked. I had stuff in there but it was either too tonally serious for the movie or it was too quirky. Nothing worked. I went to Bill and said, “I just don’t even have something to point you to in terms of what I think might work musically for this.” I did a lot of talking about my thoughts and he had to find a way to translate that into the music. He did a lot of different takes on sort of a single cue. It got to a point where I think both of us were a little frustrated; not just with each other, but with the inability to find something that spoke to the tone of the movie, which as you know, is serious but also has comedic elements that is weird and quirky and kind of plays all these different tones. But, all of a sudden he sends me a cue, and I’m like, “That’s it! That’s what’s right for that! Now, just build everything out from there.” Then he just goes. Once we land on that right sound, on that right cue, he can go away and sort of really flesh out the rest of the music.

You mention the word “quirky”, and I think that’s a perfect word, because as I’m watching the film and listening to the dialogue, we have a former MI5 spy who knows more about American television and pop culture than our American photographer does, and I just got a kick out of the pop culture references to “The Honeymooners” and “I Love Lucy”. Those were really nice touches, kind of a reverse counter-culture reference.

That was Adam’s idea. I’ll give him total credit for that. He liked this idea, and I did too, but he liked this idea of this secret agent who’s training, put her in a position of understanding America solely from the point of view of these very dated references and shows that she had watched growing up and then sort of continued to watch, and then had an understanding of America through pop culture and not through any kind of actual experience. We thought that would be just another sort of example of her honing in on something very specific that doesn’t seem to have any kind of reference for anybody else in the real world.

You also did the cinematography on NEGATIVE. Is it because of the creativity and the experimentation that you, yourself can do, that you also like being your own cinematographer?

I’d gotten in this place where I’d been wanting to do it, and NEGATIVE felt like the right film to do it on because (1) we’d save money, (2) it was low-pressure, and (3) I just thought that NEGATIVE needed a different approach than what I’d seen before with other DP’s, who I love and I’ve worked with and will continue to work with. But they’re looking at something different than I’m looking at it, as a director. I’m looking for time. What I don’t have on a film is time, and I need to find a way to create time, and if that means sacrificing the lighting or lighting in a different way or making use of camera technology now to shoot in lower light situations, I want to be able to do that. The way we shot NEGATIVE was to shoot for 38 days over the course of six months. Getting a DP to come back every day and worrying about their schedule was something I didn’t want to do. And I just saw in my head how to execute it, and I thought I was probably going to be operating the whole film, anyway. I’ve learned, too, that what I do as a director with the actors and the performance is directly tied to how I use the camera to enhance and support those performances, so I need to be there with the camera doing that. And I need to create an environment on set where the actors are not feeling restrained in any way. So it’s easier for me if I’m also the DP to say, “We’re just going to do this.” To just collapse that conversation and move quicker and allow for more opportunity for performance and more takes rather than, “My name’s on it as the DP, and I need to be protective of that.”

You bring up a good point with utilizing the camera. I’m curious what camera or cameras were you shooting with and what lenses? I’m looking at this and I’m thinking primes or sphericals, maybe?

I’d say 80% of the movie was shot on the C100 Mark II. The Canon. Mostly because (1) I owned it so I could use it whenever I wanted and, (2) I’ve always loved Canon’s color. I was okay shooting in 1080p, as opposed to 2K, 4K, 6K or 8K because (1) that’s expensive, (2) it doesn’t really get you anything other than saying you shot in 4K, and (3) I knew that I could handle at home, within our budget, a 1080 work flow, instead of a 2K or 4K or 8K work flow. Then for a couple scenes, including the fight scene and a couple other shots, we shot on the P300 Mark II using Canon, the Canon Cine Primes. For the opening sequence where Natalie’s overlooking the city, where she’s lighting everything on fire, and during the shootout sequence at the end, we shot on Canon’s ME20 which is their low-light camera that allows you to shoot at like 4 million ISO. We didn’t shoot at 4 million ISO, we shot at about 25,000 and 100,000 ISO, which allowed us to basically see in the dark and allowed us to bring up a couple of lights, a few crew members, very little equipment, and shoot those nighttime desert scene blitzes. That sequence was also shot on the Canon Cine Primes. For the rest of the movie, when we were on the C100 Mark II, I actually shot it on the Rokinon Cine Primes, mostly because I owned them so I could use them whenever I wanted. I don’t know if anybody looking at it could tell you what kind of glass we used, so that goes to show you all the time and energy and money that goes into getting a certain kind of glass, if that’s stopping you or getting in the way of you being able to make the movie, then just make it with what you’ve got.

That finale night sequence is absolutely beautiful from a color standpoint and a texture standpoint. We really get the differential in the different tones of blacks and the shapes of the desert. It picks up beautifully for that blue-black inkiness.

That’s a testament to Canon’s camera that it’s such a high ISO and in so little light, you’re able to really find those different shades in there. I think the depth that you get out of Canon, to me, is a greater value than resolution or anything else you get out of other cameras.

You’ve got a very eclectic background, Josh. You’ve made shorts and features and even some tv series over the years, and wearing different hats. Now you’ve completed NEGATIVE. So I have to ask you, what is it about feature filmmaking, what is the gift that feature filmmaking gives to you that keeps moving you forward?

I think that it’s an opportunity to really focus on sort of the “autureness” that feature film gives directors. Some of my favorite directors, like Soderbergh and Michael Mann and David Fincher, guys that their work is tied to them so directly, those are the guys that have always spoken to me in terms of their approach to filmmaking. When you see a Michael Mann film, you know you’re watching a Michael Mann film. I think that what’s always been appealing to me about features is that features can give that to a director in ways that, even nowadays, serialized dramas don’t. So everything I’ve been doing has been kind of finding ways to have the freedom to really do the things the way that I want to do them and not be in a position where I have to service any other need. The nice thing about doing stuff with a lower budget is, you get to not only do that, but you get to use it as an experiment and you get to try things and you get to really hone your skills and see what works and what doesn’t without the same pressure that you would have on a 10, 20, 50 million dollar movie. I think that for directors nowadays, one of the things that is unfortunate about the loss of sort of the mid-range budget movie is directors getting to sort of express themselves as directors in ways that they don’t get to on a Marvel movie. You think of Chris Nolan, who did “Insomnia”, which a lot of people loved, but a lot of people didn’t see, as a stepping stone towards doing “Batman”. He probably still would have knocked it out of the park, but you wonder what that “Batman” would have been if he had gone from “Memento” right up to “Batman”. So I feel fortunate that I’ve been able to play in a sandbox with some of these smaller budgeted movies. I’ve been able to execute them in the way that I got to have this creative freedom to do it the way that I wanted to. Even in this case with MarVista [the distributor], they really let me make the movie that I wanted to make. Their suggestions in editing were mostly about just trimming things that honestly should have been trimmed and cut to begin with. So they were very supportive of the vision, and it’s been really about that, which is a vision and being able to craft films so that when somebody then hires me to do another film, they’re hiring me because of that. For me, that has always been the appeal, which is from an aesthetic point of view. I like the freedom that features allow for in ways that other mediums don’t.

by debbie elias, interview 09/20/2017