Photographers the world over died a thousand deaths in 2010 when the only remaining photo lab which processed Kodachrome film, Dwayne’s in Parsons, Kansas, announced it would bring this 75-year era of Kodachrome processing to an end. Kodak had announced in 2009 it would stop production of the chemicals necessary to develop Kodachrome film and one by one, labs ceased processing until Dwayne’s was all that was left standing between Kodachrome and its extinction. Long a favorite of professionals and amateurs alike, Kodachrome was created in 1935 and was the first film to effectively render color. With an almost celebratory richness, Kodachrome’s treatment of light and color is something for many, which cannot be achieved in today’s digital world, delivering a “truth” that is often masked with mechanical tricks and tropes of digitization. Kodachrome has long been the format for some of cinema’s greatest films and the world’s most famous photographs. Even Paul Simon celebrated Kodachrome in a song. Shining a light on the end of Kodachrome and Dwayne’s in 2010 was the now publisher of The New York Times, Arthur Gregg “A.G.” Sulzberger with his New York Times piece, “For Kodachrome Fans, Road Ends at Photo Lab in Kansas.”

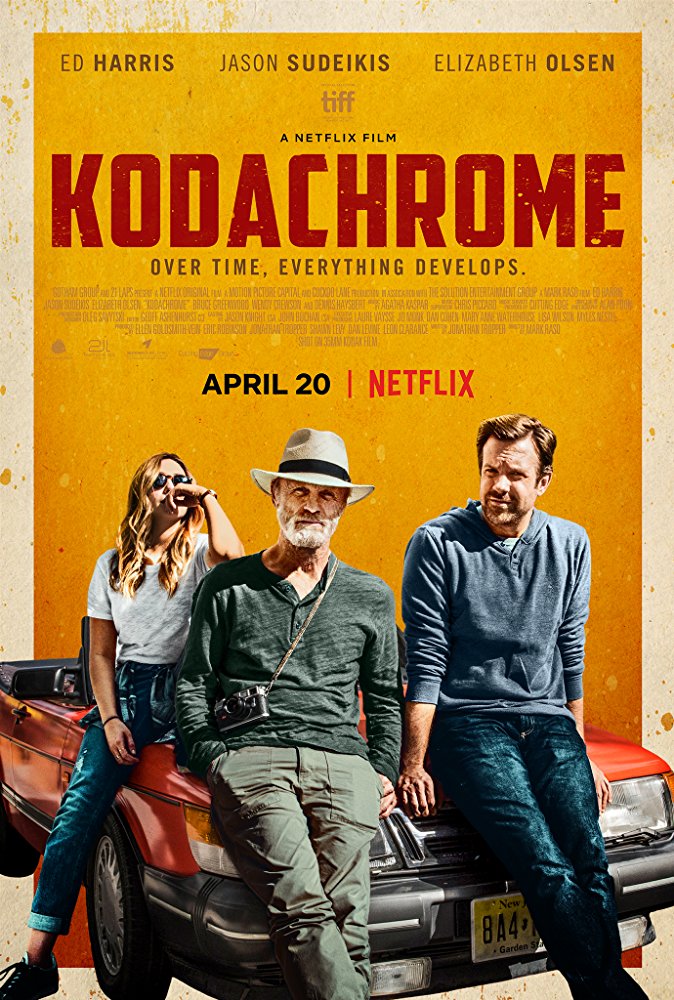

But the love for Kodachrome and the phenomena that surrounded its final breath in Parsons, Kansas never died. Picking up the mantle from Sulzberger are writer Jonathan Tropper and director MARK RASO who were inspired by Sulzberger’s article as the foundation for Raso’s new film, KODACHROME. Starring Ed Harris as photographer Benjamin Ryder (inspired by the works of award-winning National Geographic photographer Steven McCurry), Jason Sudekis as his estranged son Matt Ryder, and Elizabeth Olsen as Benjamin’s caregiver Zoe, Tropper and Raso deliver a film shot on film (Kodak 5207 and 5219 35mm) which a richness of character, story and visuals to rival the excellence of Kodachrome film itself. A road picture, a reconnection of father and son, a passing of the torch from an analog world to that of a digital one (figuratively and literally), through it all we see the truth of the artifacts of life. As Harris’ character Benjamin says, “Photographers are preservationists.” So are filmmakers.

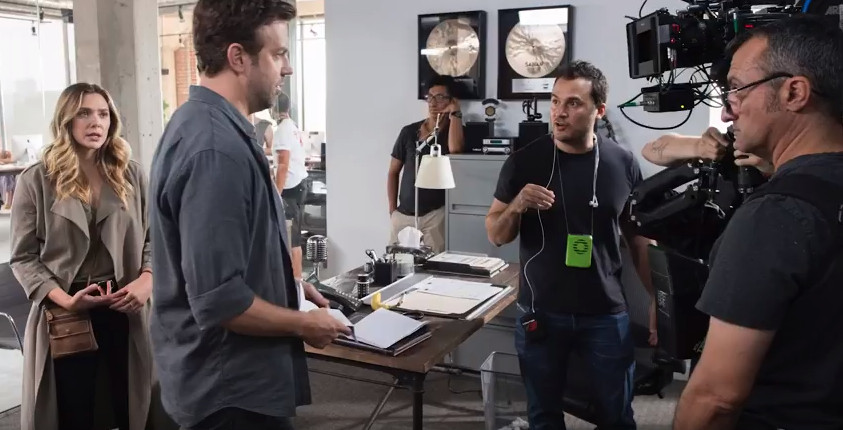

I had a chance to speak in-depth with director MARK RASO in this exclusive interview talking about KODACHROME. Stretching himself as a director since his last film “Copenhagen”, one can see the growth in his characterizations, dotting the “I’s” and crossing the “T’s” to create a true cinematic experience.

Take a listen now as Mark and I talk about the poignancy and metaphor of KODACHROME, the reflections of life, developing a visual tonal bandwidth, casting and performance, and of course, the magic of shooting on Kodak film.

How did this project come to you? We’ve got the great allegory here but we cannot escape the fact that we are talking about Kodachrome, a very visual medium with the truth that comes out with the true colors and the lighting, which you and Alan [Poon – cinematographer] have exquisitely explored with your visual tonal bandwidth here. I’m curious how the film came to you, and then how you and Alan then approached this cinematographically to design the film?

The script was sent to me as a new father. At the time my son was six months old. We had recently moved to Los Angeles for career reasons, and kind of grappling with this your artwork versus family thing. When I read the script, I instantaneously took to it and happened to be reading it with my son in my arms late at night, three in the morning after he wouldn’t go back down to bed. So I just started crying when I got to a certain scene in the film. I knew I had to do this film. That’s what brought me to it.

Once I got on board. . . you try to find the spine in the film, you try to find themes that can carry you through. It was this idea that along with the depth of film and the depth of the Ben character, there’s also the Matt character, Jason’s [Sudekis] character was in this place where the music industry was moving basically from analog to digital. And what this means in society and this time that we’re going through. That’s what really drew me to the film, as well as, this idea of moving forward. Character-wise I felt like in order to move forward, we have to let go of the past. It’s a perfect metaphor for, in terms of photography and music and stuff, we don’t wanna let go of the past. A lot of us don’t wanna let go of the past, we don’t wanna move forward, and we have to do it. It’s this dilemma we find ourselves in. That was really the through-line and what we want to focus on.

Visually, when me and Alan sat down, a lot of our initial discussions were based on this reflective moment and how we can bring reflections into the film.

I have to say, Mark, you and Alan make the greatest use of windows and mirrors for that very purpose, of reflection and duality and two worlds existing within one. It is so exquisitely done, so I applaud you on that.

Thank you very much. Yeah, that was one of the things we started off on. Also, we had this idea to introduce all the characters through a pane of glass. We intro them all through this pane of glass. Again, wanted to kind of mimic the way Ben sees the world. He has to put this thing in front of us. . .When we start this film, there’s no clarity involved with these characters, they’re all kind of struggling, they’re all kind of obscured with where they are in their life. These are these visual scenes. Those are the ones that we were able to carry through the film. Another one we tried to do was to put Matt’s character in frames, so to speak, in window frames and door frames, or at best, as much as we could try to stay tight, almost like he’s trapped in the photo himself throughout this whole film. We stayed extremely tight on him. We really wanted to restrict him and put borders and frames on him representing Ben’s photography and what that does, and then allow that to open up at the end once they kind of connect. We’re as wide as we ever are with him. We see more sky behind him. We let him in during the frame in these wider shots. Something like that was a little bit tricky to navigate.

The final thing we did which was the most complicated thing was we decided that we didn’t want to have Matt and Ben alone in a clean two shot until they’d connected. We kept them separate the whole film. Sometimes they were together in the same frame, but Lizzie’s character would always be in it with them, so it would be the three of them, but just the two of them, we wanted to keep them separate to visually put a stamp on this idea that they are so disconnected. They are so disconnected we don’t even want them in the same frame together. It got tricky on us when we’re shooting a lot of the car scenes because we ended up a little bit tighter than we maybe wanted to be, but once you kind of see through this vision, it goes.

I really feel like it pays off once they are together at the end, once they’re on this road trip and they’re together in Kansas. You see them together a lot for the past 15 minutes of the film that Ben’s in. You really get the sense that they’ve connected. Then I think we’re trying to work on a kind of subliminal level here, but we think that’s something that pays off. Those are kind of the tools we use to attach. It’s good to always have some sort of guidelines to attach the film.

Another thing we did was we tried to replicate as much as they are separate and not seen together, we also wanted to shoot similar shots to kind of convey this idea that they are father/son. They have the same traits. There is bloodline. We oddly enough, looked at tons of photography books. We looked at tons and tons of photography books and tried to get inspiration. One place we found inspiration from was a painter, Alex Colville. He has these really interesting shots. Often people’s faces are obscured and it’s on their back and we kind of really liked the subtext in the painting. We tried to have the shot of Matt looking out the window and then later replicate it later in the film with Ben looking out the window and have it pushing on Matt’s back and pushing on Ben’s back. It’s kind of this idea that these two characters, connect them that way, connect them visually through these shots.

That was our big overall blueprint for the film.

Your blueprint worked to a tee. It is perfection. I love how you mention the frames because when we first see them together when they’re going to embark on a road trip and Matt’s sitting on the stoop, what do we have there? We’ve got all these old oversized, old, broken picture frames there which I thought was beautiful . . . I chuckled when I saw that, because I knew with the character of Ben seeing everything through a lens, there would be a lot of framing. You didn’t disappoint me. And I’m so happy you had a convertible because I can just imagine as much difficulty as you had with getting shots, individual separate shots in the convertible, you would have died trying to do it in an enclosed car.

I know. It was a little bit of a tricky one. The car stuff is always time-consuming and tricky. In the end it worked though. I think it worked out okay.

It really did. Throughout the whole film, it was very evident Matt and Benjamin really are two peas in a pod. They’re cut from the same cloth. The one pushes people away and looks at life through a lens. The other one pushes people away because he doesn’t want to get close enough. He’s on that record that just keeps spinning in one circle. You really, really maintain and build on that. When you get to your 51-minute mark and you start with that monologue that Ed Harris delivers talking about the beauty of film and Kodachrome and the idea of artifact and seeing things, at that moment, your emotional shift just intensifies. That’s where things really start to explode. Then not nine minutes later in the band scene where Matt’s trying to sign a band, that’s when you really start intensifying and shifting and you finally start bringing them closer in subsequent shots. It is so powerful. Right in that hinge mark there, 51-minute to about an hour ten, that’s where you really take off and you send us into that third act that just explodes with emotion. So well executed.

Thank you. I hope people continue watching to get to that point.

Oh my God! You’re riveted getting to that point. It’s fascinating watching these characters unfold. We learn about them with Elizabeth Olsen, Zoe being the glue, the conduit by which they connect. When you get to that point, that is like the heartstrings are really pulled. You really start rooting for a reconciliation of some sort. When you get to Dwayne’s photo shop, that was it. I was in tears the rest of the film. How exciting is it for you as a director to actually shoot this film on film on the 5207 and the 5219 and use 35?

It was pretty awesome to be honest. I had shot a short film on 16 maybe 15 years ago or something, maybe a little bit longer than that. I loved it. I just never went back to it because it wasn’t quite practical on a lower budget. Finally it made so much sense for this film to shoot it on film, on 35. When we pitched it, when me and Alan pitched it and we got the okay and we got tremendous support from Kodak, it was great on so many levels, but aesthetically obviously you can just tell. I know people can say you can’t tell, but-

You can tell.

You can always tell. I think digital images can be very beautiful, but you can tell. What it did, more so and what I forgot … I used to dabble in photography and developing my own photos. I’d kind of forgotten how precise that process is, how you raise the camera and you frame the shot and you wait and maybe you don’t take it because you have a limited commodity in terms of the amount of photos you can take an then you wait until you get it right and then you take it. It was kind of the same thing on the film set. We had to get it right in camera. Our playback, we didn’t really have playback, but our monitor was standard definition, so you couldn’t rely on it to see the true image. You had to get it right. Everyone on set was so in tune and so present and so in the moment on every shot. You can hear the film rolling through the camera. It really did something.

I shot my first feature digitally where you shoot it and you press the button, you watch it, you shoot it again. You don’t worry. You keep going. In terms of shooting on film for KODACHROME, we just had to get it right the first time. We wouldn’t be seeing [dailies] . . . We had to ship the film out . . . It was driven out to another city five, six hours away to Montreal. We’d see it two days later, so we had to get it right. It just made everyone in tune and on the same page. That element I was not expecting at all when we decided to shoot on film for aesthetics, but what it did in terms of on-set was fantastic.

Do you think shooting on film has helped make you a better director in terms of your visual eye for what will work and what won’t work for a shot as opposed to digital where the mindset is, “If it doesn’t work, if this isn’t right, if that isn’t right, we can just do it again, and again and again.”?

Yeah, I think there’s value to doing exercises and shooting stuff and going out on weekends and shooting stuff and exploring, but when you’re on set and you’re on budget and you have to do things a certain way, there’s definitely the fact that we were shooting on film made me a better filmmaker and I had to be more precise. I just had to be. There was no alternative option. In that case, yes.

No sloppy seconds allowed in film.

No. Exactly.

You have the most incredible cast here, Mark. From Bruce Greenwood and Wendy Crewson to Dennis Haysbert. Then, of course, you bring in Ed [Harris] and Jason [Sudekis] and Elizabeth [Olsen]. I think Ed was attached first, but how did you luck out with this cast? What I find interesting about this cast is because you have someone like Ed. You have someone like Bruce and Wendy. They go back to the days when everything was shot on film. Then you’ve got somebody like Jason and Elizabeth who are so used to all of their work being shot digitally. You have a nice blend of talent. I’m curious as to what led your casting with each and then how their own experience with the different shooting mediums might have influenced their performances or how they approached the characters?

I think we got tremendously lucky and fortunate. Ed was cast first. He was the guy I thought of when I read the script. To get him, it doesn’t happen very often. It doesn’t work out that way very often. It was awesome. Jason came on board. Jason is such a great guy as well, just smart and understood what we were trying to do, a photographer. Jason’s a fantastic photographer. He shoots stills and he shoots on film all the time, so he had an understanding of it and the process. Really, really he’s really, really good. You have to check out his work. Lizzie, oddly enough had shot on film a few times before. She had shot “Martha Marcy May Marlene” on film. She had shot another one on film. She was more used to it. Ed had done it before. He’d just come off shooting “Mother” which was also shot on film. He was used to it. I think Jason it was something a little bit new, but he was such a film buff that he was talking to the guys all the time, the camera men, trying to figure it out. I remember I talked with Jason and he really loved hearing … It’s such a thing to him that you can hear the film in the camera. He really got a kick out of that. He said it made him more in tune, kind of what I was saying before, more present. It really sharpens you, especially when you think of it as money. Think of it as money going through a camera. You’d better get this one. They had all explored it, experienced it. No issues whatsoever. They were all excited by it. they all felt because this film was called Kodachrome it’s just a film that should be shot on film.

How hard was it to get this cast aligned? Bruce is always working. I think I’ve seen four films in the past month that Bruce is in. Jason’s always working. Lizzie. They’re all always working, but for the stars to align to get all of them in one film. . . I know you have an incredible producing team. Dan Levine, I know him. We’ve talked much over the years. You’ve got a great producing team at bay, but still, no matter how good your teams are if those stars don’t align for you to get this cast . .

It’s patience. It’s a small film. It wasn’t like we said we’re going this date, jump on or jump off. We had cast a film and then we were at the mercy of scheduling for probably eight months from when we originally wanted to go. Then when we thought we were going to go, we had to end up pushing two more times to find this window late August to early October. . .Ed and Lizzie had just come off one film and then before Jason was about to have his second child. We had this window. It was very specific. Bruce could give us a week, but it had to be a very specific week. We wanted him, so we had to adjust the schedule to make sure we were shooting his stuff during that week. Dennis [Haysbert]. We were fortunate that he was shooting a TV series where we were shooting in Charles, so we had to also adjust the schedule. When he had off days there, we would shoot his stuff. We were all very flexible to make it work with the cast that we had. It is tricky. It’s extremely tricky.

I would be remiss not to ask you about your music. You got Chris Paccaro as your music supervisor. Your needle drops are fabulous. Then Agatha’s [Kaspar] score also, fill-in score, really nice touch. It never overpowers. It doesn’t lead you. It lets you follow because music is as equally important as the visuals here because of the very nature of Matt’s characters.

Exactly. For me, that’s what was dictating the musical choices. I wanted to listen to it through Matt’s ears basically. I wanted this music to be stuff that he would listen to, stuff that he would enjoy. The more modern stuff. . . There’s a few shadows to Ben’s music as well, but specifically the Graham Nash song. Chris and I had kind of discussed what I was looking for. He was great providing ideas and we’re obviously on a budget and we wanted to keep it 2010 because that’s when the film takes place. We wanted to keep everything in that frame. We were super lucky that Jason happens to be good friends with Eddie Vedder. We got a Pearl Jam song that way. Still paid for it, but not as much as it would have cost. Then Agatha was someone that I’d worked with on my previous film “Copenhagen”, like Alan, and also before that, my short film I had worked on with Alan and Agatha on those. I was struggling a bit with music and called her up and just sent her the film and asked for help. She quickly got a couple things. She just got it right away. I sent it to the producers and she’s like, “Yes, she understands it. This is great.” She worked tirelessly late in the process just to get everything in order and as you said, bridge those gaps and guide us, but not push us. I’m thrilled. In that case, it helped so much to have shorthand and previous relationship.

I do have one more thing that I’m going to ask about – the importance during your end titles of actually having Steve McCurry’s photos in there. You could not have done this without some of them and to see them, my heart just exploded.

Yes. I had reached out to Steve pretty early in the process. He was so forthcoming and generous with his time. We chatted quite a bit. I wanted Ed’s character to be, his works I would say, to be based off Steve’s work, not his life, but his work. Ed was in New York doing a play and Steve had just come back from a film shoot. I asked them if they could meet up and they did. They got along great. Then eventually we asked Steve,”Can I use your work for Ed’s character’s work?” He was very generous to allow us to do that. I just think it brings a certain validity to Ben’s character. We see some of it in the house when we’re in Ben’s house earlier, but I really wanted to, at the end of the film, show we get a sense that Ben has been absent. We know he’s been absent. We know he’s been off doing this other thing, but I wanted to put a print on what this other thing was. I wanted to say this is where he’s been. This is the work he’s been doing. Steve’s work plays for Ben Ryder, Ed’s characters work, at the end.

It’s beautiful. It also lets people, the younger generation, actually see and understand the beauty of what Kodachrome really was and why Kodak needs to bring it back.

They’re working on it. For so much of us, Kodachrome is just like presentations and slide presentations in school. It’s a fun thing in family trips and stuff like that, but there’s so many beautiful photos when professional photographers do it right.

interview by debbie elias, 04/13/2018