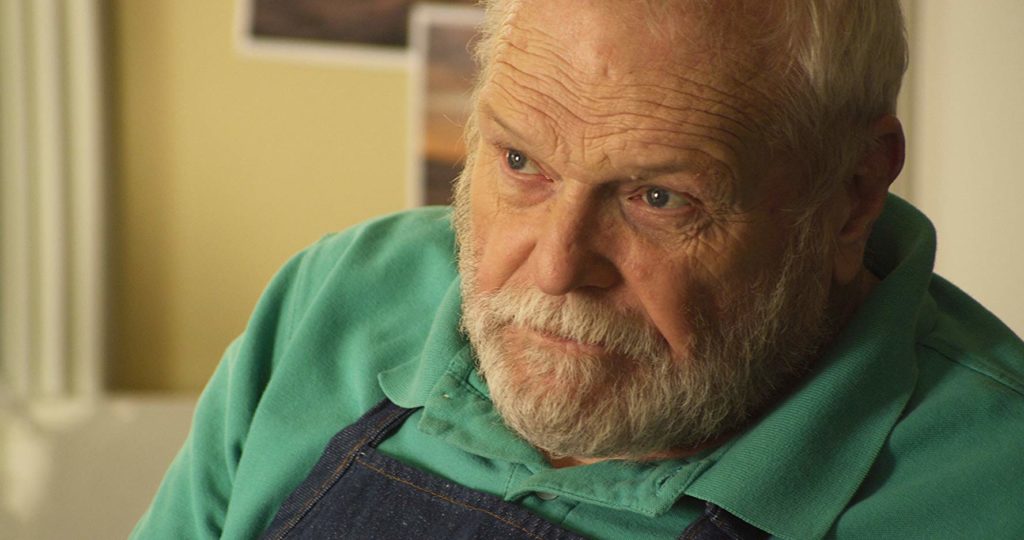

LARRY CLARKE. You know him. He’s “that guy.” “That” guy. The detective, the cop. the lawyer, the morgue guy, the priest. Yep. “That guy”. With more than 20 years of big and small screen appearances to his credit, LARRY CLARKE now makes the move behind the camera and adds writer/director to his resume with a look at the behind-the-scenes “business” of death in the semi-autobiographical charming, funny, yet poignantly endearing 3 DAYS WITH DAD. And while loss and death are very somber and sobering experiences, somehow humor inherently finds it’s way into the mix, giving all a moment of respite, a moment of perspective, a moment or two of joyous remembrance and laughter, and more than a moment of insanity. 3 DAYS WITH DAD touches the heart and tickles the funny bone within each of us.

How many of us have been touched by the death of a loved one, a family member? And possibly even more emotional, watch a loved one go from thriving and vital to a mere shell of themselves, unable to function or communicate as the body shuts down and death comes? It’s heartwrenching. And that’s where 3 DAYS WITH DAD begins – at the funeral for family patriarch Bob with four combative adult siblings – Eddie, Andy, Zac, and Diane, plus brother-in-law Tim – each reverting to a childlike state of behavior, and Dawn, widow and step-mom, at obvious odds with her step-children. In other words, an average dysfunctional American family complete with the fears, fun, fights, foibles, and flaws that we all know so well.

Poignant in its observational humor, 3 DAYS WITH DAD celebrates the insanity and craziness that surrounds the fictional Mills family. Clarke spares no feelings and is brutally honest with his observations. But it’s from that, that humor comes. We see and feel through Eddie’s eyes as the odd man out now plunked down in the middle of familial chaos and tasked with giving the eulogy at Dad’s funeral. Part of the challenge that Eddie faces is that in order to deliver what many would deem an “appropriate” eulogy, he must come to terms with his own life, his relationship with his dad, and particularly his past, something he must face head-on during the three days of dying, death, siblings, a step-mom, and funeral arrangements. It’s his journey that carries us and where LARRY CLARKE ups the ante even more with his performance as Eddie. Clarke is a triple threat!

Calling upon his own talent and expertise as an actor, Clarke excels with his casting of actors who know how to play well with others in the sandbox. You can do no better than Clarke’s casting in 3 DAYS WITH DAD. Tom Arnold as Andy. Mo Gaffney as Diane. Eric Edelstein as Zac. Jon Gries as Tim. Larry himself as Eddie. Then he taps Brian Dennehy, who delivers the most vulnerable and sensitive performance of his career as Bob, and Lesley Ann Warren who knocks it out of the park with the meatiest role she has had in years as Dawn. For some added comedic spice, Clarke then brings in JK Simmons as a newbie funeral director trainee and David Koechner as the doctor you may not want near your loved one at life’s end. Then to add some youth and vigor, young “General Hospital” star Hudson West comes onboard as Devon adding a wonderful tacit element akin to the “circle of life”. Each fuels the funny with an honesty that is pure, palpable, and resonant while the dialogue is natural and easy. Delivery is sharp and befitting each character, timing even sharper, a testament to the skill of each actor.

Expounding on his casting, Clarke, together with his cinematographer Chris Gallo, not only keeps the film’s visual tonal bandwidth light, but keep the film well lighted with natural light, avoiding the darkness of the subject matter at heart. A pleasant surprise that flies in the face of what many first-time directors do, is that Clarke gives his actors the physical space in which to play thanks to framing and a freer blocking. Editing has a nice pace to it and for the most part, allows scenes to breathe and allows for lines of dialogue to land without feeling rushed. Clarke also pays great attention to the film’s score, tapping the talents of John Ballinger as composer who delivers a lighter hand with nice lyrical flow mirroring the fluidity of the camera.

3 DAYS WITH DAD belies LARRY CLARKE being a first-time feature director. He brings everything he has learned over the course of his career as an actor and puts it to use here as a director. Casting is superb. Production values are excellent. Clarke knows this story, he knows the characters, he knows his audience. And he knows when to just sit back and finish his eggs at breakfast.

As if talking with an old friend, LARRY CLARKE was as open, honest, and candid in our extended conversation as he is with his storytelling. After seeing his directorial work with 3 DAYS WITH DAD, it’s clear that LARRY CLARKE is a storytelling force to be reckoned with. His innate humor rises to the surface at every turn, as does his infectious chuckle and laugh. Nothing was off-limits as we dug deep into Larry’s experience of making 3 DAYS WITH DAD. From the inspiration for the story, the writing process itself, performance, the wearing of multiple hats, editing, scoring, distribution and delivery, lessons learned, the “kill your darlings” choices, his consideration for his actors and what they needed to give their all, and, of course, how you get around the production crises, Larry talks about all with refreshing candor and surprisingly, unending enthusiasm. But one thing comes through loud and clear, LARRY CLARKE is grateful for this business and for the opportunity to stretch himself and now move into directing while he continues to act. Director LARRY CLARKE is here to stay.

I am so enchanted with 3 DAYS WITH DAD, Larry. Having gone through the death of both my parents and dealing with my three siblings, there is nothing untrue in this film. It is so honest. You could have even gone even deeper into the madness and mayhem! You tackle so many of the emotional elements and events that happen. And everybody’s childhood comes to the forefront.

Yes! Yes! I could have, and I did, and I ran out of time. After a while, people were like, “We get it. We get it,” like, “It’s too depressing.”

I don’t recall seeing any film that has really tackled this with the deft with which you do.

They normally skip this part. Normally, they’re like, “They’re sick. They’re sick.” Then you see them die, and then everyone’s sad and moves on. But I’m like, “No, you missed all the important stuff!” Which is the weird part, which is the dying part. And then there’s the hospital, then there’s the family, and then there’s, of course, dealing with the stuff afterwards or as I call it, “the business of death” where you’re not prepared or have the energy or time to do any of that stuff. And all of a sudden, that’s thrust upon you and everyone just starts to crack.

As I watched, I was taken back to when my mother passed. My parents had made no arrangements for anything. And three days before she passed, the doctor’s saying, “Look, she’s not coming out of this. This is the end. You’ve got to make plans.” He called me in a panic after he was at the funeral home making the arrangements for plot, burial, and all that stuff. “Oh my God. Oh my God. Do you know how much it costs to get buried? I just had to pay $23,000! And because she’s dying very soon, they don’t give you a time payment plan. You have to pay everything up front!”

It’s true! Yes! I had a whole scene with the funeral home director, the death certificate stuff. But I had to cut it. It was like, “No, I don’t have time.” I had way too much. I could have made a mini-series out of this movie for real.

You could have. And I would watch every single minute of it, Larry. But the key here is how you’ve structured this, which I have to commend you on from a directorial standpoint. We start with the funeral. We meet people. We meet the family. And then you take us back, and we’ll jump back and forth in time throughout. But never once do we ever lose our place or forget where we are.

That’s interesting. That’s the biggest challenge. I’m open to the most criticisms as far as that. My whole thing was, I said, “I don’t want to watch a linear movie where people are wondering whether he dies or not.” I had no interest in that whatsoever. But what I was interested in doing was really just showing Eddie, kind of starting at the funeral. When you’re going through this process, as you know, when you’re sitting in a hospital or you’re sitting in a funeral, your mind goes back to what you’ve been through the last two weeks. Then even sometimes you go back to childhood and then you come back to the present moment. And that happens quite a bit. So you can live so much in your head and you’re exhausted, and your body is kind of in shock. So I wanted the audience to start to have an experience of death.

I really think that you encapsulated it. For anybody who has never experienced this, I think you paint a very good portrait for them, of what they might anticipate. And for those of us that have, watching this, it’s like, “Yep. Yep.”

And it’s also a little bit of a dig of me at Hollywood because people die so easily in Hollywood. People get shot and we’re all so used to bloodshed and death in movies. But when you really look at death though, if you’re going to really write a story about it, just one single death, and it’s devastating. I didn’t want to make a horror story. The absurdity of death is the number one reason why I wanted to write this stuff down, because I thought, “Well, this is absurd. Oh, this is incredibly ironic. This is really dark funny,” and that was happening the whole time. Everything was just so goddamn ironic and strange in that way, and then poetic in some kind of strange way. I had this father who was so strong. And then he was so weak. Then he wouldn’t go. He kind of wouldn’t die. Then we had this “incredible” healthcare system; like the nurses didn’t talk to each other and everybody’s messing up. The diagnoses are all changing and they’re like, “What?” The doctors wouldn’t talk to each other, and you’re like, “Oh my God.” Everything’s kind of representative of what I went through. But I couldn’t get into great detail, though I wanted to, to really show what it’s like. I would have made it a mini-series.

The whole commentary that you give through subtext on the healthcare system is spectacularly done. The way you have a line here, a line there, so well done. The cafeteria scene is fabulous.

So finally the doctor comes, yeah. And then sobering, he had to get that diagnosis. Of course, it’s about money. That’s what it is in the American system of death; they deny that death is coming. They try to spend as much money as they can on the individual that’s dying. A phenomenal amount of money is done with testing and operations and stuff, for people who are obviously going to die.

As a first-time directorial for you, was it always your intention to direct this?

I knew I’d be doing it on a shoestring, and so I knew I’ve got to pull it off in a way that I know how to pull it off. I knew I was going to be the most passionate person in the room, and I knew I was going to have the most on the line. I also knew I was going to put myself in it because I can control the tone from set by being in the scene, and I can go very quickly that way and go even quicker as I don’t have to talk to my lead actor and worry about tone or whatever. I could just slide right into the scene. Then the actors kind of vibe off of you, what you’re doing.

When it comes to actors, the cast that you have put together here is amazing! You’ve got Tom [Arnold]. I would not expect Tom Arnold to be playing a character who walks around a holy roller with rosary beads!

I know. He didn’t even know what a rosary was. He goes, “Hey, Larry, what is this? I’m Jewish. I don’t know what the hell this thing is.”

And you’ve got Eric Edelstein whom I adore.

Oh, he’s the best. He’s fantastic. He’s one of the best people I’ve ever met, and not just in the show business, but in life, period. He’s just a unique soul, and his monstrous talent, and a huge heart. Just a huge heart.

But you round out the siblings with Mo Gaffney in there, who’s hilarious. And I have to commend you, on behalf of every “General Hospital” fan in the country for casting Hudson West as little Devon. GH fans are rabid for anything the show’s actors do and Hudson has a rabid fan base.

I’m having a premiere tonight. I don’t even know if I’m going to recognize him because these kids grow up so fast, and I shot it two years ago. He’s got that impish kind of handsome grin. I had no idea [about “General Hospital.”] All I know is that he’s a pro. And I was going to not go pro. I was going to try to save money. And I’m glad I didn’t, because he saved me so much money. You just turn the camera and he’s a star. And he’s inquisitive and curious and professional. Sometimes you think you can get a real kid to pull that off, and I couldn’t. And I’m really glad I cast him. I can just say he saved my butt. He saved my butt.

You get a kid like Hudson who’s been doing “General Hospital” for a number of years, this kid knows how to hit his mark. He can go through pages and pages of dialogue.

Yes! During the auditioning process, they sent me like, I don’t know, 12, 15 kids that auditioned online at the casting director’s level, so they just sent in their reals. Then they sent them to me. They were all pretty good. And then his came out and I went, “This guy pops. There’s something different about him. He’s really honest.” I wrote the casting director, and I go, “Is there something about him that’s…” And they went, “Absolutely. We’re so glad you said that. Can we just cast him and move on, please?”

You’ve got strength with your young actor. You have strength with your 40-something actors. And then you bring in with supporting roles, JK [Simmons] and [David] Koechner. But then you get Brian Dennehy. The most vulnerable performance I’ve ever seen from him.

Brian Dennehy, yeah. He was the one. He was the linchpin. That’s really great that you said that. Thank you.

And, of course, then, Lesley Ann Warren. This is the most significant meaty part she has had in forever!

Can you just say this to a bunch of journalists and have them all agree with you? Because it’s what I’ve always wanted them to say. I’ve been saying it since while she was shooting it. I was like, “Lesley, you’re killing this role. And then you’re freaking me out because you’re acting just like my stepmother.” She really did! I don’t know what happened. We would talk about it. It was like the wig moment. Whenever she put the wig on she transformed, and I was like, “Where did Lesley go? Oh, there she is. There’s Dawn.”

Even in my notes to myself, as I was watching the film, I have down, ‘Costume and hair!!!’ From the tight cigarette pants to the sweaters, the shoes, the sunglasses, that wig! Phenomenal character transformation. And you put all of these people together, and the comedic beats; and nobody misses a beat, Larry. How much of this was actually on the page? How much was improvised, because it is all so spot-on with where the laugh comes? You feel it all naturally.

It was all written. Then I have looseness on set that I like when I go to loose sets, when I have a director that believes in me. Some people would pitch an idea, like, “Hey, I’ve got something for you. Can I do this?” And I always, as the director, would be, “Sure,” because I wanted to create an open flow. These guys are creating. I wrote this thing, but you don’t really find out what the scene is until you get there and everyone’s talking. Then I would know right away intuitively which lines didn’t work, or what was cut, or what was too long. Poor Lesley. She showed up one day, and I said, “Okay, Lesley. You know how you’re supposed to come in and say this line?” It was the line where they’re arguing about the abortion. Normally she just came in and said whatever the line was before, something like “Hey, I’ve got to go walk the dogs.” But I said, “No. You’re actually going to bring in his [funeral] suit, and you’re going to be in a ghost-like state. It’s going to be at night and you don’t know what you wear when you get cremated. It’s going to chill the room.” I gave her the lines. She goes, “What? Wait a second.” Kind of like, I threw it at her. A nyway, I wrote that last because I wanted a button on that scene, and I wanted something that was kind of around the corner, something comes in, and it’s just scary. And it’s just scary and sad. And you can’t help someone with these thoughts. Anyway, I wanted a taste of that. So I got inspired and I told her that, and so she did it. Then in another scene I threw something at her. I like getting surprised on set. I like when actors get surprised. So I would mix things up. Then sometimes I’d change the lines while I was with them in the scene. So you see the real response on camera. And they love that stuff, because it’s like play then. Then your set is a lot of fun because it’s alive. You can see the actors are creating their characters. They know they have the utmost respect from me because I’m an actor first and then a director. My whole thing is like, “This is your playground. Let’s go, because you’re all the best at what you do. Let’s go. Let’s have fun.”

Obviously, you are an actor’s director because of your decades of acting experience. So you understand how to work with the actors, how to create, how to give them their playroom with room to play.

I really do. I’m also like a director’s actor, so I tend to do things and bring a lot of unsolicited advice to my directors and it doesn’t matter who I’m working with, whether it’s Steven Soderbergh or if it’s the Wachowski sisters, or Frank Oz. I’ve walked up to everybody and I’ve always had something to say, like an idea, or something with the script, or something with blocking. And just about everyone always is like, “It’s good.” They know right away if you know what you’re talking about, if you want to add to the scene. If you’re just some idiot actor that would be a big mistake. I generally tell actors, “You don’t have to bring a lot of questions to a director on set because they don’t have time. But if you are solving a problem for them, they like that.”

I’m glad you mention the blocking because so often we have actors that become directors or try their hand at it. And they get into the technical aspect of directing and their mind goes blank, or they’re so far behind the learning curve.

Yes, because they think just because they can direct people emotionally or they have an idea, they think it’s about emotion. And it’s really not. Actually, emotion’s the last thing. You don’t even have to worry about emotion because that’s generally covered. But it’s all angles and camera blocking and actions with your cast. I want things moving. A lot of my scenes always started with movement. And I always kind of messed up the set and created something for people to look around, or deal with, or something. I always like that. So that when you turn the sound off you really should know what’s going on in the scene. You don’t really need the dialog because it’s a visual medium.

That’s one of the great things with your cinematographer, Chris Gallo. The two of you, with your visual tonal bandwidth, you keep it light. You keep it lit. It’s light in tone. And it’s well lighted with natural light. It’s refreshing. You could have gone darker, which many directors would have done. But you didn’t. And you made very judicious use of closeups. You have few, if any, ECUs. And you have a fluidity in very claustrophobic spaces. The hospital room, there is no real room to navigate cameras in there.

There isn’t, no. Well, when you’re in those spaces and you live in them, I wanted the audience to feel like they’re living in a hospital room because they’re stuck in there. That feeling of being in a hospital is unlike any other feeling when you have a loved one there who’s sick and dying. It’s just a horrible feeling. But everything happens in the microcosm. Everything happens within feet and inches inside a hospital room, because there’s so much drama there. I have to say, I wanted to shoot in a real hospital. It was $10,000 a day and that was over my budget. First, it was in my budget, but then it was over. So I had to create another idea and so I had to build my hospital on the set. I built this as a set. I had to come up with shooting ideas. For example, with Brian in his room, I came up with this idea that whenever we go back to the room it’s a different angle. We see a different side and it’s also different lighting. You’re in the same room but it’s night. Or you’re in the same room and we’re looking at the other side. It worked, but because out of necessity I had to do that. I just always remember looking across from my dad and seeing someone else sitting or someone else waiting or someone else sleeping, and dad sitting in the chair. I just have all these images of that room and all that life we had in it. But I would have loved to have had the ability to swoop in a little bit more with an actual room and hallway leading in. I would have liked that. If I had more money, I would have done more hospital stuff. Over the last two years, I see some independent movies that take place in hospitals, and they obviously shot up in Calgary or they shot somewhere in Canada where you get the whole hospital, and I would always sit there and have location envy because I go, “Oh my God, look at that shot! They can walk and talk down the hallway. Oh my God!” And I couldn’t do that, because I didn’t have money. Plus, my cast wouldn’t leave LA. That’s the only reason why I got these guys is because they’re like, “No, I’ll give you day. I’m shooting something else” or, “I’ll give you half a day, Larry.” JK [Simmons] gave me a whole day. He was the whole day. Did four scenes in one day. He worked like 13 hours. But all my friends were giving me something. You save money also in hotel rooms , too. You don’t have to put people up. It makes things a lot easier. I shot LA for Bel Air, Maryland. That’s really what I did.

And it works, because you don’t have a lot of exteriors. It’s very contained. But something that you and Chris also do in the hospital scenes, the funeral home, you always try and, when the siblings are together, keep all of them in the frame so that we’re not getting coverage shots of reactions. We’re seeing it all as it’s happening.

That’s interesting that you say that. I always had a little coverage going, depending on the shot. That’s interesting. Depending on the shot, depending on the scene. My coverage was always getting people altogether. I would pop in just for responses or some stuff depending on what was going on. But I wanted to catch the gravity of the moment. For example, like the big diagnosis and we’re going to have an operation scene, where everyone’s in the room. The whole family’s there and two doctors are there. That is loaded with drama. So I covered half of the room in one way and half the other way. And I wanted everyone included. Then, of course, I did a little bit of coverage. But it was like a grand stage and everyone’s getting the news all at once, because they’re basically saying, “Your dad’s going to die. We have a 5% chance of this thing working. But we’re going to go for it.” It hits everybody different, and I wanted to see that, see everyone going, “Oh my God. This is it. You’re not going to have another meeting like this again about your dad. This is the last meeting.”

One thing that I love with your character of Eddie is that because Eddie lives in Chicago, he had to fly in. You do have coverage shots with Eddie popping in and out on occasion. But it also just further metaphorically solidifies the dynamic and status, so to speak, of the siblings that are right there and who live there, and that are around Dawn and dad all the time and Eddie is treated like an outsider coming into the established family unit.

Yes. Yeah, he’s thrust into the situation. I’m glad you picked that up. I had more coverage of that. Again, I had an airport scene that I had written and things that I ran out of time for us, so I had to really choose and change and rewrite just to try to get those ideas in that he’s an outsider, without having my Chicago scenes, or not having him in Chicago Airport. But when we got down to actually shooting that stuff, my producers said, “First of all, we’ve run out of money.” Second of all, everyone went, “Well, I don’t think we need it. I think we can cover this other ways.” So we cut those scenes.

I think it works beautifully to have Eddie as the outsider popping in because you always get the sense of what are these three or four, when you figure Eddie’s brother-in-law in the mix, up to. That resonated strongly with me because I was the outsider with both my parents illnesses and passing because I’m in LA and they’re all in Philly.

Exactly. And the siblings are saying, “You’re just coming in and acting like you’re going to make decisions. We’ve been doing this for months. We’re with him all the time.”

Right. And I really appreciated that perspective you bring.

I’m really glad that you got this film on as many levels that you got. This is one of the first interviews I’ve talked to someone that’s picked up this much of the movie. So I really appreciate your insights.

Thank you, Larry. My privilege. There is just so much about this film. There’s a great truth here at its heart and its core. And you follow it through on every level, even right down to John Ballinger’s score. And I love John’s work. He scored for Dorie Barton for her debut feature, “Girl Flu.”

John was great. It was real with John. John was an add-on. I had made some music with John and John made an album with my brother. Composing isn’t his first thing. He can make amazing music and albums and whatnot, but composing is the job that he wanted to start doing more of. And he told me that. I said, “Well, listen, John. I got another guy and I’ve already started working with him.” So I started with this other guy who’s really big in the business. Then he all of a sudden got a Netflix job. What we did, it was very unique. I used his temp tracks, this guy’s temp tracks, when I edited it. Then I brought it to John ad asked, “John, can we match it? Can we do better?” So that’s what started our conversation. And he did. He matched it or did better with just about every single thing. Then we came up with a sound, this kind of Irish sound with a little bit of a French organ playing. I like to borrow a little bit from the French cinemas, especially their comedies, their sad comedies. There’s always an organ. There’s like a hand-organ playing, which I always find sad, but it’s not that sad. There’s feeling and you think, “Oh, I love it. Like a clown. Like a sad clown.”

And here again, just as you and Chris did with the visual tone, you do it with the composition, with the score. You never bog us down in something where you feel the shroud of death.

That’s essential. The first scene that I wrote, the thing that inspired the whole movie, was that I heard a song, a composer, Dustin O’Halloran, who works with pianos and very simple scores. I heard his music once, and it blew me away because all of a sudden it was a death scene. I could hear the death scene. And in my head, I went, “Oh, it’s a death scene with no sound.” And that’s what it’s like. It’s like a sad music that plays, and even as horrible as it is, it’s all poetically correct. Not poetical. It’s poetic and simple, but you don’t hear a thing. You just hear the piano. That was the first thing that came into my head and it really inspired the movie. I worked around that. Then the movie really does lead up to that moment. My brother saw the movie and he was like, “It’s really interesting how we pull off the ending. I forget about the death at the end.” Of course, we’re going to show the death because we’ve kind of forgotten it, even though we started with the funeral. Of course, you’re going to show the death but it’s kind of hidden. You kind of get surprised by it. I tried to do it in a way that was just beautiful and sad and we don’t really watch the gruesomeness. I didn’t want to have Brian [Dennehy] in the shot at all.

Independent filmmakers always have to worry about distribution. How did you get distribution? What did that process entail? This had to be something new for you as well.

I had distribution deals almost right away. It wasn’t an easy sell to distributors. It really wasn’t. We got a lot of interest. And then when it came down to it, I finally found Unified and they were brave enough to go, “Okay. You’ve made a movie that’s unlike a lot of movies we have. You have a dark comedy.” And dark comedies, that’s a bad word in the distribution world because like my distributor says, “There’s no such thing as a dark comedy. There’s only comedies.” And I go, “Well, they’re going to be a little surprised at the end when dad dies and you get some tears coming up, and you’re gut-punched. But this isn’t a Will Ferrell comedy about hospitals and death. It’s not. And they know that. But they’re like, “Well, you know what, Larry? We’re going to sell it as a comedy. And when they get in, they’re going to find it out.” So I said, “Okay. It’s up to you guys. You’re in the business of selling. I’m in the business of making.”

The contracts alone, and delivery, for the last six months delivering movies. People don’t know anything about moviemaking. They have no idea the hell of delivery when you have to actually deliver the movie around the world, to the theaters. It’s like re-shooting the movie again. It just takes so much time and effort and money. Even though in this scale, this small scale that I’m at, which is independent movies, it’ss eye-opening to me. I know that next time I go around, I want to have more of a producing partner who knows a little bit more about the business, so I don’t have to do so much of that because I was just overwhelmed by it. They would throw a contract at me where they’d mention some technical aspects of the movie and I would go, “What is everybody talking about? I have no idea what you’re saying right now. I do not understand why your download didn’t occur the way you wanted, or what speed you had it, or why did we lose…”

There was a time where we lost three days of shooting where we lost the connection of sound to the monitor because someone kicked the cord out. When that happens it means there’s no sync. There’s no sync on the sound. So we had to find the sound. Then the computer that you go into to get sound recognized that as a different input. So all of a sudden they start scrambling it. We spent probably two weeks just on those scenes that we shot those two days because the monitor wasn’t plugged in correctly. And you’re hoping against God that you have the sound because I didn’t even know if I got it correctly. You’re just hoping, did you get it? Is the movie there? So we’re fighting against that. We’re fighting against this. We’re fighting against editing platforms. We did this thing in Adobe, and I was told Adobe was the way to go. Then I got to my editors and they said, “What’s Adobe?” They go, “Where’s the Avid?” And I go, “They told me that the output should be in Adobe. That’s going to be quicker.” He goes, “Well, not quicker to me because I’ve never worked on it.” I said, “Well, you’re supposed to be able to do the Avid, and the Adobe can make an Avid board.” It can create an Avid language. So you get a keyboard that’s Avid, but it’s really Adobe. So they did. And he goes, “Yeah, that’s true.” He goes, “But it’s not really. And it’s so intricate with the editors. I mean, these guys are dealing in a level of intricacy which is mind-boggling and I can’t help them because I have no idea what you’re doing. All I know is that I can’t see the scene. I can’t see the scene in both monitors. Why not? Well, it’s because of this. They say the kids are using Adobe but I don’t even think that’s true and anymore. I was told we’re going to save money. We lost money because I had to use three different editors, including the last one, Tara, who saved my butt because she did the final pass and it really made the movie. She has a wonderful ear and eye. She brought a lot to my movie. She kind of transformed it.

You’ve now made it through. You shot 3 DAYS WITH DAD two years ago. You survived editing. You survived shooting. Now, this film is coming out in the world. As you sit back and look, what was your directorial learning curve, and what did you take away from this experience that you can take forward into your next project, be it as an actor or as a director?

Well, that’s a big answer. But let me tell you, I really liked directing and acting and I was better at it than I thought. And, of course, that was the biggest challenge. Everyone was like, “Larry, you’ve never directed before. How are you going to pull that off?” I never really had a doubt in my mind that I could pull that off just because that’s just the kind of an actor I am. Of course, you’ve got to show that confidence on set. You’ve got to show it. You have to control a set, because if you don’t control a set, meaning if the first take of the very first day, you come in and they do the scene and at the end of it you go, “All right, let’s… Can we… All right, hang on a second.” If you show that you don’t know what you’re doing, the crew, inside, they’ll be like, “Oh God. On no.” Then the actors will be like, “We’re not safe.” Or have this feeling of like, “We’re working with an amateur. I was given a note from a friend who said, “No matter what the first take is, print it. Everyone’s going to go, ‘Thank God, this guy’s directing. We’re going to get through this day.'” So I think I did that. think I actually did the first take and went, “That’s great. Print that.” I think we did another angle after that. The learning process has been phenomenal. It’s something I want to keep doing. I’m really bored as a character actor, obviously, so I made this movie because I fall asleep on my sets now and I’m not challenged anymore. I’m bored out of my mind. Not to say that I’m not thankful. I like working. But it isn’t like they’re giving me the detectives who are like Kojak. I’m not playing those interesting guys. I’m playing kind of dull guys. And I don’t see that changing really. So I wanted to show Hollywood “This is my new reel. This guy, this big character guy, yes, he can actually lead a movie. He can also get the girl.” And they’ll watch a guy for an hour and a half who’s not Brad Pitt. And because I don’t second-guess their intelligence, and because I’m telling a good story. And because everybody looks like a real American family, so I made everybody big when I cast everybody. It was like I wanted Tom’s big face, and him and Mo, and Eric. I was like, “I want an American family.”

Then you counter that with petite stepmom Dawn.

That was all preplanned. Absolutely, and very much like life. But there is something about casting and size and character faces, that I don’t see. The casting world and film and TV is going a certain way. If you look, there’s a lot of beautiful people on TV now. I mean, they’re just beautiful people. And I get so tired of good-looking people. I hate to say that. But in the ’70s you had guys like Jack Warden or even Gene Hackman for that matter, who had a rich face, but you kind of fall in love with Gene Hackman. The guy was not handsome if you think about it. He was handsome, but he wasn’t handsome. He was a character actor who acted handsome. He had charisma. And I can give you a whole list of actors that we all used to watch and you fell in love with them. So is Brian Dennehy. He was this big, lumbering guy, and all of a sudden he’s playing sexy roles? He was downright sexy and charismatic. And people ate that up and they loved it, and there was a richness in the storytelling and a relatability to people that are like that in real life. What I feel like we’ve gone back to is the golden age of staring at movie stars and falling in love with beauty and perfection and people that don’t want to see fat people. Let’s perfect everything and let’s just stare at Brad Pitt for the rest of our lives. And we’ll all be happy and have sexual fantasies or something. Or just try to attain a goal of our bodies and an image that we’ll never, ever, ever, attain. Immediately, in my casting, I really wanted to show just a bunch of faces that were different. I would have loved to have gone with different ethnicities, but I was in Bel Air for Maryland, so I’m making the point about that. This is an Irish-Catholic community and my family’s all White.

I did not make this movie with a commercial bone in it. Everything was true to myself. And I wrote it in front of a live audience in this particular actor’s night that I go to. We were able to bring in 10 pages. That’s how I created it, at this reading night that I do every week. So I really wanted to hear it and see if I could write something dark and funny, so the laughs were very important. Then I started to get this tone and this style. Then when I would go a little too dark, I’d ask the audience, “Was that too much?” They were like, “No, we love it.” They really got the absurdity. So I started to develop this tone and I finished the piece. So I had this thing. But in a way, it’s a script that Hollywood never would have made. They won’t make this. So I said, “I’ve got to do it myself.” And that’s pretty much how I’m going to approach the rest of my career. I will stick to my guns because I love the dark comic tones. I’ve got three more movies that I’ve written. They’re ready to go. They’re similar films to 3 DAYS WITH DAD. Some of them are a little more, I would say, commercial, but I want to move people and I want them to laugh and I want to do it through great dialogue and rich characters and challenging situations. So when I write, I want to stay interested as an actor every time I turn the page. And if it’s not, I’d change my writing. I did the same thing with the editing. I was like, “I’m being bored. Cut out. Let’s get out of the scene.” You’ve just got to constantly keep your nose to the grindstone, your hand to the fire because that is what I’m going for. I’ ve got to keep pushing it. And that’s the challenge of storytelling. You tell a story where you say, “I have a story and I’m going to keep your attention. And I want to keep your attention. Obviously, yes, I’m going to make it thrilling at points. But I want to keep your attention with stillness. I want to keep your attention with focus. I’ll introduce heart and love, and people love that stuff. And a lot of filmmakers are afraid to do stillness. They’re afraid to do broad strokes and topics like this. They’re like, “Oh my God, you’re going to scare everybody.” I got feedback when I wrote this. They go, “Oh my God, you’re starting with the funeral? No, I can’t make this picture. You’re starting with the funeral? Put the funeral at the end.” And I said, “No, it’s not about the funeral. It’s actually about Eddie. It’s about Eddie coming alive.” Eddie kind of grows up and that’s what the picture’s about. I don’t want to tell a traditional story, because you tell traditional stories, our audiences are so quick these days, they’re so fossil. They’ve seen everything. So you’ve got to challenge them. You can’t just lead them by the nose and tell them what your movie’s about. The audience WILL get it.

Making 3 DAYS WITH DAD has been one of the most challenging experiences of my life. I think that moviemaking is the hardest thing to do in the world. If you don’t think that’s true, then try to make a movie. That’s all I can say, is that. At one point, near the end of this, I don’t think my line producer will mind this, but it was one of the last days of shooting. I was so burned down. I was sick. I had bronchitis the entire time I shot the movie, horrible bronchitis. I had to stop coughing to do my scenes. At one point I had to get my ear drilled out because both my ears were blocked up with fluid. I was sleeping three hours a night. I wasn’t doing well. I’m done. So I’m across the street having breakfast. It’s 7:30 and everyone’s doing their load-in. And I talk to my line producer. She’s like, “We’re doing the load-in.” I go, “Great. Just tell me. I’ll see you guys at 8:15. I’m just going to have a nice quiet breakfast and prepare for the chaos of the day.” I wanted to be completely alone because I knew for the next 14 hours it was going to be an assault of just constant, “Larry. Larry this, Larry.” Everyone’s always saying your name and you’re having to solve problems. I get a call 15 minutes later from someone else. They go, “The line producer just tripped over a box and she dislocated her elbow. And five fire trucks are now in front of your house. And your neighbors are angry because they can’t leave their driveway.” You know what I did? I said, “Handle it. She’s going to get taken away, and I’m sure she’s going to be fine. I’m going to finish my eggs.”

by debbie elias, exclusive interview 09/10/2019