ALAN CASO is a name that many within the film industry immediately recognize as one that represents excellence in cinematography. With almost 50 years in the industry, Caso started his career as a grip, working his way through the lighting and lensing ranks into camera operation and ultimately cinematographer, garnering four Emmy nominations, three American Society of Cinematographers nominations and two wins, one being the prestigious Television Career Achievement Award. Along the way, Alan has delivered some of the most beautiful and telling imagery to be found on the big and small screens. From television series like Six Feet Under, Big Love, Hawaii 5-0, American Gothic, and Into the West, to made for television movies like A Father for Charlie and Running Mates, to television mini-series Frankenstein and George Wallace, to feature films like Muppets From Space, Reindeer Games, and First Sunday, Alan Caso is a true storyteller with light and lens. And he keeps on going!

And while many recognize Alan Caso for his outstanding cinematographic work, others may know him best for his recent, and very vocal stance on sexism and ageism, which he articulated on accepting the ASC Television Career Achievement Award, set forth here, in part:

“I’ve found myself ashamed and appalled, especially while working abroad or here with talent from other countries, by the blatant racism and sexism on display. I happily joined the choir of outrage about the Neanderthal ways in which this administration wants to send this country back. But it only took a couple of people rolling their eyes at my outrage that I realized how much of a hypocrite I was, complaining about racism and sexism while surrounding myself with an almost exclusively white and male crew.

I have no excuse, nor can I justify the many years I spent in a bubble worrying about only myself. Now, this isn’t an easy career for anybody. You book one job, and before that job even ends, you start worrying if you can book another one, so you can cover your kids’ insane tuition bills. But if that’s the pressure I felt throughout my entire career as a white man, I can’t even imagine what it’s like to try and have a career as a woman, a person of color, a woman of color.

I have sworn to myself that I will spend the remaining years of my career mentoring and kicking some doors in for aspiring cinematographers who don’t look like me. I started this effort last year, and I can tell you, those doors we installed over the years are many, solid, and not easily moved. And I won’t be able to do it alone, so I’m appealing to my peers and my colleagues in this room tonight. You can avoid a moment like I’m having here, standing on a stage admitting you were blissfully asleep in a bubble of your own privilege for the majority of your career. Let’s not only kick in some doors for members of minority groups, let’s uninstall them for good. Let’s surround ourselves with a crew who looks like the real world, not like an Ivy League fraternity.”

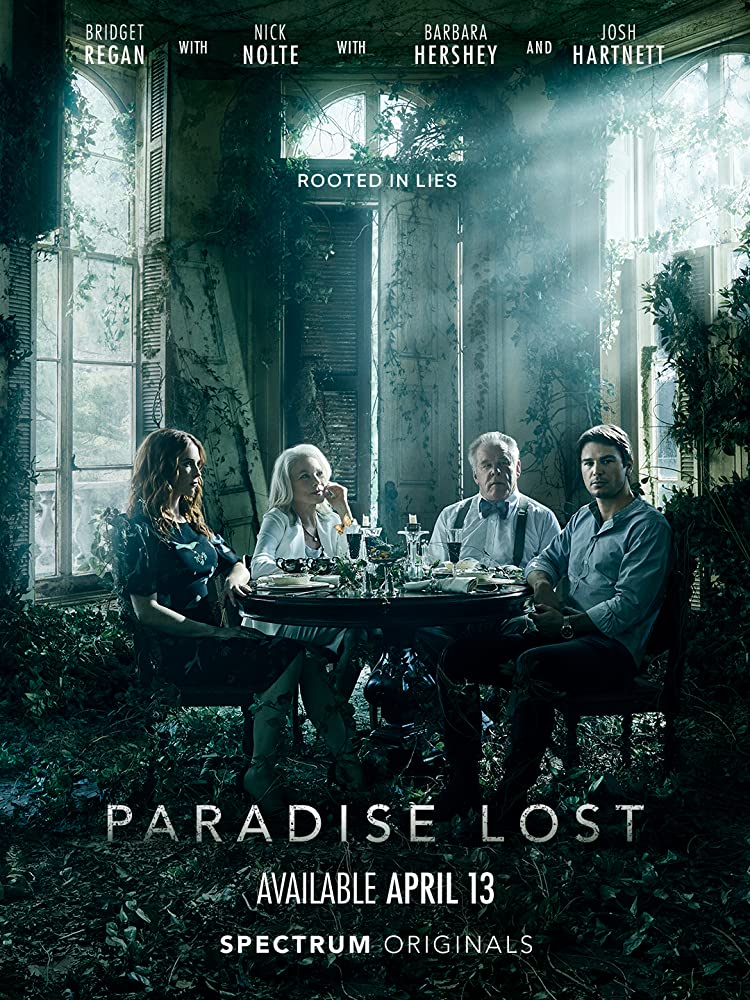

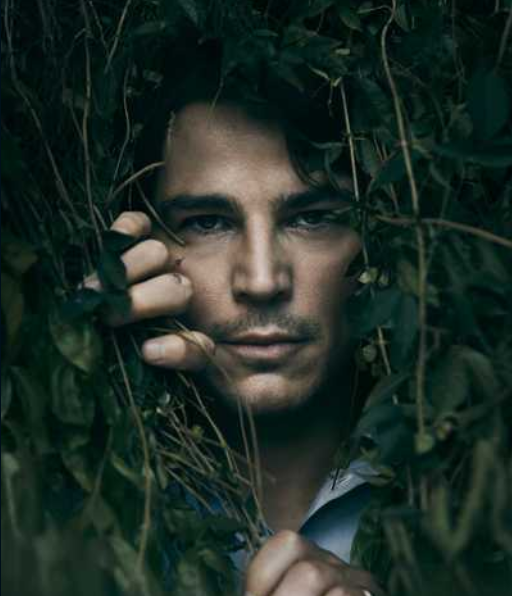

Those words rocked not only the film industry but spread like wildfire on social media and through the general public. What sets Alan Caso apart, however, is that he doesn’t just talk the talk, he walks the walk, as exhibited when pairing up with fellow cinematographer, NICOLA DALEY, for PARADISE LOST, a 10-episode Southern Gothic mystery series about a psychiatrist who moves with her family from California to her husband’s hometown in Mississippi where the Forsythe family reigns supreme with generations of secrets and skeletons just there for the digging. Created by Rodes Fishburne, PARADISE LOST is shot in the Deep South and boasts a cast led by Nick Nolte, Barbara Hershey, Josh Hartnett, and Bridget Regan as the Forsythes, and a supporting cast of luminaries which includes, among others, Gail Bean, Danielle Deadwyler, Elaine Hendrix, Shane McRae, Silas Weir Mitchell, and Jason Davis.

NICOLA DALEY is an accomplished cinematographer in her own right, known for her work in Australian and British cinema. With almost 20 years in the field to her credit, much of which includes the dual duty of operating the camera in addition to the cinematographic work of designing and establishing lighting and framing to achieve the project’s visual tonal bandwidth, Daley has dazzled with her work on projects like the acclaimed short film I Am Emmanuel, the TV series documentary SEX: The Unnatural History, the series The Letdown, and the lauded Deborah Haywood directed feature Pin Cushion. But even with all of her experience, PARADISE LOST represents a new challenge for Daley as this is her first U.S. production. Of course, who better to partner with for this learning curve than Alan Caso.

While cinematography is cinematography is cinematography, with PARADISE LOST, the cinematographic experience is more than just “point and shoot”. It’s about bringing the vision of the director and producers to light. It’s about serving the story and designing and crafting the visual tone of each individual episode cohesively and synergistically to tell the complete story arc, something made more challenging by Daley and Caso each tackling different episodes, while still allowing each cinematographer to put their own stamp on the final product. Sounds difficult to achieve on the best of days; hair pulling on the worst. But the proof is in the pudding, as the cinematography of PARADISE LOST is exemplary.

While Caso was assigned an episode or two more than Daley, don’t think for a second there was any inequity in the division of labor, as Daley was the one responsible for what I believe are some of the most visually powerful and stunning, pivotal episodes in the series. Beauteous and telling, CASO and DALEY capture the authenticity and realism of the South, bringing that region and its residents to life on screen. Celebrating nature’s bounty, they each make magic happen from capturing the thickness and moisture hanging in the humidity laden air to exposing the beauty of a location defining algae-covered swamp. They create depth and texture drawing metaphoric walls between people and the past and present with light and lens. They show us the socio-economic and familial divisiveness that fuels the world of PARADISE LOST thanks to judicious framing applications. They immerse us in the ambience of this time and this space. They give us unforgettable moments defined literally and figuratively by their work. And what they each do lensing Nick Nolte and Barbara Hershey, the patriarch and matriarch of the Forsythe family, is glorious.

So how do two cinematographers from opposite sides of the world come together to create a world like PARADISE LOST? For Nicola Daley to be a “fish out of water” in the Deep South of the United States experiencing a union-driven work system for the first time? For Alan Caso to follow his own words and break down the barriers of sexism and ageism? The answer is easier than you might imagine. Collaboration. And this is one amazing collaboration.

I had a chance to delve into the world of PARADISE LOST in an exclusive conversation with ALAN CASO and NICOLA DALEY talking everything cameras, lenses, color correction, drones, logistic challenges, continuity threads, collaboration, and so much more. They are in synch at every turn, be it in the mindset towards filmmaking, approaching a story visually with camera and lens, or their appreciation for their craft. And they are fun! But our conversation wasn’t limited to just the series. Alan and I took a trip down memory lane recalling his early days as a camera operator on the film House, the fun of Muppets From Space, and the less than six degrees of separation between us over all these decades before finally getting to chat now, while Nicola reflected on British and Australian production versus that in America or “Hollywood” before we all dug in our heels discussing inclusiveness, diversity, sexism, ageism, and the whys/why-nots of cinematographers moving into directing.

Thank you so much for doing this today!

ALAN CASO (AC): No, thank you for having me aboard. This is terrific, I’m very excited.

So, let’s talk PARADISE LOST. I binge-watched this whole series not just once, but twice.

AC: It’s great. It’s a great show. Isn’t it? I wish you could speak to Rodes Fishburne on that, and also the people of Paramount. I don’t know why they decided not to do another season of it because I think it’s a great show.

I think it is fabulous. It is so engrossing and the characters are just fascinating. To see Nick Nolte in this role is wonderful. And then to pair him with Barbara Hershey, and in such an important role in the series? Fabulous. Fabulous to see him as the Judge. And the way that both of you light and lens Nick and Barbara. . . Barbara looks spectacular.

AC: She did, didn’t she? She looked really, really terrific.

NICOLA DALEY (ND): Yeah.

One thing that the two of you did that I noticed that was consistent through all 10 episodes, and I so loved seeing this, is that you took advantage and you really celebrated – especially with night shoots and lighting – you celebrated the humidity in the air because humidity in the South is like none other.

AC: You couldn’t have paid a bigger compliment than saying that right now, because that was definitely the single first order of business. At least I think, and Nic correct me if I’m wrong, but that seemed to be the one thing that everybody was preoccupied on as far as the visual scopes. That they wanted to feel the thickness, the humidity, the overbearing heat of the South.

ND: Yeah. And I think that went across departments, right? Because talking about Nick, and we were talking about Nick sweating through costumes and stuff. And I remember Rodes was like, “No, people sweat in the South.” It was part of the texture of the show. I loved that about it.

AC: He wanted to see the sweat rings and he wanted to see the perspiration on the faces and stuff like that. He was very adamant about that.

For me, it was about the humidity hanging in the air; that it was palpable.

ND: It was great. It was real.

AC: It was brutal. Then there’s just a lot of bugs.

I’m surprised you don’t have bugs stuck on the camera lens. I’ve seen that happen before.

AC: Yeah. It took some getting used to.

ND: I remember the crew kept saying, because a lot of them are from New Orleans, “Why are we shooting in June and July?” A lot of the time we have summer off, and then we start again in September. But that was such an integral part of the show, I think. What do you think Alan?

AC: Yeah, exactly. I think Rodes did it on purpose. He’s from Mississippi, so he knew what we were getting into. He’s used to it. I will tell you something though. It gets really cold during the winter. I was down there in the beginning of 2016 in January, beginning of January, to shoot on Roots, and I spent some really cold nights. Some of the coldest nights I’ve ever spent in the swamps. It was below freezing, easily. And there was rime and frost everywhere. It was really cold. You get that too, but I think also it was an exceptionally cold winter for them down there at that time, that year.

Not only do we get to feel the humidity and see it in the air, but the way both of you, on your respective episodes, the way you use light – headlights, twinkle lights – that really just enhances it. There are so many shots in multiple episodes, night shoots with light, with this mist, which gets heavier at night with the humidity, and it creates this emotional tone of dread, fear, and mysticism.

AC: Yeah. I think that’s what Rodes was hoping to get. Nicola and I put a whole book together in the very beginning visually of what we wanted to do. So I think we had some pretty good guidelines on where we wanted to be, what kind of lenses we wanted to use, and the kind of lighting we wanted to do. We had a very clear plan laid out ahead of time before we even started shooting.

You shot the Sony Venice, and I think Sony A7S as well.

AC: Yes. We just used those. They were sort of like our crash camera. When you need to get a camera in some tight spot, or we were mounting it in a tight spot in a car or something like that. But we used the Venices because we had to deliver a 4K.

What are you going to do now when people want 6 and 8K? That’s one of the things I missed that they canceled the NAB convention this year. I always like to see what the new or next technology is. They’ve been dangling 6K for a while, and it was supposed to be a big 6K/8K presentation this year, but sadly Coronavirus had other ideas.

AC: Well, the cameras aren’t there yet. Really. I mean, not in any appreciable form. The Venice can be so interesting.

ND: It’s a big question for post-production of TV as well. Here in Britain we still do 2K for some shows. So it’s a big file storage question, like, how are they going to store all that 6K and 8K footage. That’s the big, big problem I think.

What lenses did you end up using for this? Something that I find striking with both of you is that you are very, very judicious, and very limited in your use of closeups. Similarly, wide shots. There are a few times you go wide, but everything is pretty much mid-shots, a mid two-shot, a closeup of two. So I’m curious what lenses you went with here?

AC: Well, a lot of that’s editorial. We shot a lot of the show in wide shots which they ended up not using. We wanted them to use it, we talked about it in the beginning, but usually what happens is that when you get into the negotiation stage between the showrunner, directors, producers, and the networks, they’re always pushing to get into the medium shots and all that. They just want to be closer. It’s just a culture. It’s something that’s been hard to break because everybody who markets for TV, they still think it’s a closeup medium. And it really doesn’t have to be nor should it be because the majority of people’s home screens are big now. They have gotten a little bigger in our houses. And so it’s just kind of some stuff that’s leftover. So really, I’m glad that they didn’t go into the real tight close-ups alot because then that would have just ruined the show. So at least they kind of held back and kept the main shots. But trust me when I tell you, Nicola and I used a lot of wide lenses and we shot a lot of wide shots. It just ended up not staying in them as long. We wanted to have them be in it longer than they used it.

ND: Yeah.

You’ve got the geographic area, the topography, the beauty of the forest, the woods. I want to see that ambiance. If you’re going to be there, show me. Show me that you’re there because this entire area, it defines who the Forsythe family is.

AC: I know that Rodes really fought for wide and medium wide shots that are in that show. I’m sure he fought for it because it was really important to him to let everybody know where we really were. Because dang it, you get these TV shows that shoot in these wonderful, exotic places and they’re shooting everything in closeups. And you even see that in feature films a lot. He’s like, “Why are you bothering shooting in these places when everything’s in mediums and closeups?” It’s aggravating. [Talking lenses], Nicola, do you want to answer this one?

ND: We used a mixture actually. We used H-series super speeds and some detuned Optimas, all from Panavision. So I think it speaks to what Alan was saying about the atmosphere. Those choices of lenses sort of take that digital edge off everything. I mean, the Venice is a beautiful camera and it renders skin tone in a gorgeous way and colors in a gorgeous way. But those lenses were beautiful in making it that atmospheric Southern landscape. And we looked at paintings and all sorts at the beginning.

AC: That’s right. You’re right. Yeah, we sure did.

ND: Yeah. Wim Wenders and William Eggleston and those sorts. It’s interesting about what you’re saying about landscapes. A few of my wides made it. I think that’s so important for the South, isn’t it, because that is a character in the film and that’s what Rodes always said as well. So it’s important to show the environment as well as the character’s frames within that.

AC: If you’d seen John Lee Hancock’s cut for the pilot, you would have seen a lot more wide shots. You know, it’s frustrating for all of us, because there’s just this insistence on these closeup shots. They just want to be there.

I want to feel like I am immersed in that world, that I am standing there. And that’s why I always appreciate the wider shots, because you really get steeped in time and place when you have that.

AC: Especially if you’re using wider shots with wide lenses, as opposed to wide shots on long telephoto lenses. It’s like the feeling that you’re looking at the top of a mesa from the next mesa, a mile and a half away, as opposed to being right up next to the mesa with a wide lens where you feel like you’re actually in there.

You do have some really incredible shots in here, in the newspaper office, for example. And I think this is an episode that you did, Alan, where it’s like we’re a fly on the wall up in the corner, shooting down in the empty office. Episode Nine, The Black Dog Barked. But it’s up high on the second floor in the newspaper office and it’s empty. And there are a few instances where we have a situation like that. Episode five, Danger to Yourself, where you’ve got dutching with the camera shooting up at the kid up in the rafters, and then looking down. I love some of those because it really jars the perspective and makes you feel like you’re a fly on the wall, or you’re on the ground and you’re about to get stomped. But where the two of you really get to play are with these flashback sequences.

AC: They were fun, right?

So much fun! Number one, the color dynamic. I love watching the progression of the color with the flashback sequences, as we get more into the yellow wash, the neon look, before ultimately getting back to episode 10 with the judge going through his scrapbook and having his own flashback, yet it’s not skewed with saturation. It’s not hallucinogenic. It’s rooted in reality, more or less telling us he’s now facing up to and realizes what he has done in life. And I love that progression. But those flashback sequences, the Memphis drug-induced flashback sequences are fabulous. All of Boyd’s little trips back. How challenging was it designing that?

AC: So much of that, I’ve got to give credit to Maxine Gervais, who was the colorist of the show. She’s the one who actually came up with the initial idea. Nicola and I kept on banging our heads saying, “What do we really want to do about these flashbacks? What do we want to do?” One thing we all talked about, and I’ll say a little bit about John Lee Hancock and Romeo Tirone, who’s the producing director, we all thought let’s do the opposite thing. Let’s make the flashbacks actually more saturated than the real thing. The real-life stuff was more in the softer pastels that kind of represented that humidity thing that you’re talking about, Debbie. But for the flashbacks, let’s go a little more kind of brutal and more stark colors, skewed primaries and stuff like that. And that’s kind of all we did, but we really didn’t know what to do, and so I kind of passed that on to Maxine and said “Maxine, come up with something, just kind of show it to us and see what you come up with.” And she’s the one who really came up with this kind of skewed… They’re not primary colors, but they’re not basically secondary colors either. She found these other colors and she kept it to two or three colors. So she didn’t over-bombard you with a lot of different colors, but the few colors that she gave you were saturated and different and skewed. And I just thought it really worked well, as well, she kind of tweaked around with the contrast and stuff like that too.

I love the camera work in those flashbacks as well, especially the hallucinogenic one where we’ve got a triptych going on there that I know was done in post, but we’re looking at the camera, the movement. For the most part, you guys were shooting most of this on sticks or steady cam, but then when we really get into the flashbacks, talk about the camera movement! My God, it’s fabulous.

AC: You want to tell them what we did? Tell her about what we did, Nicola, with the 2C camera. This was Romeo [Tirone]’s deal and it was a good idea.

ND: We had the 2C 35 mil camera with the hand crank. So that was sort of the transition into the flashback and actually they used them a lot more than that, which was brilliant, I think, because it gives it that sort of jittery, secrets-falling-apart kind of mystery unfolding, which I think is brilliant. But basically, we hand-cranked it and then we reversed it and then we would jump around and it was fascinating actually. Whenever we got that out and did that, the operators would get all excited and everyone would have this sort of like, “Yeah, we’re doing the 35 mil bit.” It was sort of like everyone would just get reinvigorated again about using film and having this sort of grainy texture. But it was so much fun. I loved that, actually.

But those sequences are just eye-popping and they are, they’re fun watching them, because it comes at you, it’s so in your face that… It’s like memories, you put yourself in their shoes and memories, all of a sudden when they flood back, they can stop you in your tracks sometimes.

ND: Memories are so fragmented. You remember a bit and then another bit and kind of like a dreamlike world. So I think it’s a good tool to use for this, it’s perfect., especially that mystery unraveling, skeletons in the closet kind of angle.

There’s a lot of skeletons in this show. A lot of skeletons. And I’m talking beyond the body farm! One of the most fun scenes to watch is obviously when Dickie’s going crazy and he has all the dead bodies in his truck and he’s on Boyd’s lawn and going round and round, throwing body parts, flying out of the bed of the truck. I know from a stunt perspective, doing that, either you’re going to get it right the first time, or you’re going to have to redo it and redo it and redo it. And here, the camera is actually capturing those great donuts and movement from a crane or drone perspective as well as eye level. After the truck takes off, littering the lawn with dead body parts, we see the dirt, tire treads in the circle. It just amazed me, having worked on stunt units with similar stunts, to see the “cleanliness” of that. And all I could think is, “Did they do this in one take or how many takes did they do this one? It just looked so good.

ND: It was probably one of the most challenging things we did, Debbie. We talked a lot in pre-production obviously. We had a brilliant First AD in Jessica Pollini. We would all talk about, “Once we do this, that’s gone, that lawn, so we’ve got to get it right.” But I tell you, what happened is the truck came in and before it even hit the lawn it stalled and that happened about four times because it was an old truck. So it just hit a bump and would stall, and then we do it again and it would do the same thing. We’re like, “Well, how are we going to piece this together?” So I think we had three cameras mounted in the back of it, but all the bodies jigging around. So we had a lot of cameras on it. Then we sort of had to piece it together. We thought we could do one whole take with three cameras, but because the truck wouldn’t drive all the way in and around and out again, we had to piece it all together,. It was a lot of planning. We wanted the big reveal at the end where you go up high and you see all the bodies. Boyd comes out and switches on the security light and it’s like, “Oh shit, there are all the dead bodies all over his lawn.” It was important to have that emotional beat where you go, “Yeah. Boyd’s gone to another level now.”

The end result looks spectacular. I laughed when I saw that. That big reveal made me laugh out loud. And it’s a perfect tie in to episode one, Down the Rabbit Hole, or episode two, the Damn Beetles from Japan episode, when we actually experience the body farm through rotting parts, as the camera weaves through it. And I have to say, I do like the closeups in that episode of the body farm, Alan.

AC: Well, here’s the thing, is that when you use close-ups sparingly they mean something. But if you go into a tight close up in every scene, it has one tone and one tone only. And that’s why so many of these TV shows all have the same tone. There’s no hills and valleys in the drama. So I like shows that use close-ups sparingly.

How did you guys go about divvying up who would do which episodes here?

That was predetermined by the producers before we were even hired, how they were going to break those up.

When they’re broken up in situations like this, you’ve got a 10-episode arc here, they’re divvied up, you’re each doing something, how do you maintain the visual tonal bandwidth continuity through all 10 episodes with two different voices? While there’s one voice for the show, obviously you each have your own voice that will get infused in there some way. So I’m curious how that collaboration works.

AC: It’s always a tricky balance because you want variety. So you want the two people, Nicola and I, to have our separate inputs, but the threads that keep similarity through everything, running through it all, is stuff that has to be decided in prep. So once Nicola and I decided on the basic look and feel of the stuff that we would adhere to as a pair, as a duo, the stuff that we would do on the same plane, as far as our interpretation of those things, we each went our separate ways and did what we wanted to do. I certainly didn’t want to influence her in a restrictive way of what she would naturally bring in. I don’t think she wanted to do it with me either. I think we both wanted to feel free as birds to do our own things on our blocks, our episodes blocks. But we also knew that we had to have a common denominator for everything so that the show had a continuity and had threads that were going through it all that were similar. But you want the variety, you want the difference in the episodes. I think that’s what gives it a lot of flair and it also gives you the peaks and valleys, gives you the differences.

One of the big company continuities that I saw in every episode is you obviously set a tone with the use of light and windows. We see that with the newspaper office where you’ve got light streaming through the window, you’ve got the glass pane between the office and the quote-unquote press room. But what I found interesting is that there’s never focus on the background. The press room, anytime we’re in the office, there’s that glass there, and there’s always something. With the Forsythe family, there’s always something with doorways, with windows, and then varying degrees of light coming through. And I see this through every episode here, and I love that thread. I just love how that plays.

AC: That was one of the threads that we talked about – making sure that our compositions, and also the way we shot stuff, had the layers; and the compartmentalizing of not just the shots, what you see in the shots, but it represents the compartmentalizing of what everybody’s going through in keeping secrets, in keeping things from each other and all that. So all that stuff was integral and metaphoric as far as delivering the underlying message to the audience without being too obvious, I guess.

The entire series screams metaphor. And I find that positively delicious. I always love seeing that because it elevates cinematography. It’s not just putting a camera in somebody’s hand and saying point and shoot. When watching something, the cinematography is a visual storytelling in its own right. It’s its own layer of storytelling. It’s not “point and shoot”. And I love seeing that and I love it in something like this, where I see it consistently through the entire series.

ND: I think that’s where it was exciting, those layers and everything. Obviously they’re on the script, so I think that when I read it, and before Alan and everyone interviewed me, that’s what got me excited, was all those layers. And then visually, Alan and I thought about reflections as well. I suppose, good in the office because there’s all that glass and everything to play with, but reflections of people and what they really mean and the subtext and who they really are underneath, what they’ve been showing you in the first couple of episodes and all that stuff in a show like this is really fun to play with, I think.

AC: In hindsight, I kind of wish that I had done more of the reflection stuff than I actually did because it was something that we did talk about. But reflections are always such a difficult thing because they take time and they take concept and it has to be integral to the set design and the lighting. It’s very time consuming, so unless it’s a full-court press with everybody is on board, it’s a really hard thing to just throw together when you’re on the set saying, “Hey, let’s do this reflection shot, let’s whip it out in five minutes.” It doesn’t work out that way. To give you a perfect example of what we’d even planned ahead of time and it was impossible to do, in the very first episode when Yates is going back to his car after he meets all the guys for the pancake breakfast and he’s walking out and we see the sheriff for the first time. And he pulls up in his car and he pulls in right next to Yates. What we wanted to do is, we wanted to see the reflection of Yates in the sheriff’s window. And as he rolls the window down, there’s the sheriff. So you go from the reflection to the sheriff, but it just didn’t work. And it would have been a very time-consuming thing. We were way behind on that day and we just couldn’t get it in the time allotted. So it’s one of those things where, again, you need time to do it.

I’ve got to ask you Alan, about Claude’s adult bookstore-radio station combination. Love the lighting, the use of lighting. You’ve got the little red twinkle Christmas lights on the one hand, but then we move into an almost altar there honoring Janus [Forsythe] with, there must be at least a hundred, if not more little tea light candle lights there. It looks gorgeous. The way you’ve shot it, and with that lighting, it looks fabulous.

AC: It was kind of this warped thing, wasn’t it? And I love the actor who played Claude, with the little pencil-thin mustache. He was just fantastic. And the use of color, just to go crazy with the color in there was just so much fun. It was just audacious and bold.

That’s something that’s very interesting when you look at the series as a whole because you see the color that is in Claude’s adult bookstore, and then the only other place you really see color is in Gynni and Nicque’s Airstream. And as we watch this whole thing play out and we get to episode 10, who’s now stolen the Airstream, who has that Airstream, but Claude?

AC: That’s true. Exactly. Although, there is one other place that has a huge amount of color and that’s the riverboats. The prostitution riverboats. But once again, it has to do with sex and Claude and all the seedy underbelly of the area.

And Pouchy is a direct conduit to Claude because Pouchy was the one who was there the night of the fire. It’s interesting to see how that color ties in. Everything else is very similar, very muted, very pastel. Again, but for the flashback sequences, that are an animal amongst themselves.

AC: That’s true.

ND: It’s interesting, Debbie, as a lot of the motivation for the light is naturalistic, through the window, where’s the force in the real light. But I think in a show like this, when you’ve got elements of mysticism, you try to subtly put it in, like in the Mississippi Ophelia in Mrs. Timpken’s house. So there’s a very light purple glow when he comes in the door and when he steals the painting. It’s not very obvious because obviously, where’s purple light coming from, but it’s supposed to be this nod to the mysticism of the legends that they’ve told about the painting. So I don’t know, Alan, what you think about… It’s always interesting when you are motivating light but then you want to put in a sort of unmotivated color.

AC: I love that. I am such a fan of that, and especially what you did there. I thought it was terrific. And I don’t think you have to explain. There’s a weird natural phenomenon with light in life anyway. Several times I’d be looking at something and walking over and finding out why it’s coming that way. My wife would always laugh and say, “Nope, there he goes again. Trying to figure out some kind of light thing.” But if you are aware of it, you realize how much that actually occurs in daily life anyway. A lot of times it just has to do with the sun reflecting off a wall that’s colored a particular color, and it’s glowing on the inside of your house through a window. And you think, “Oh my God, what is that aqua blue light on my wall? Where’s that come from?” You look outside and realize, “Oh, because the building across the way is getting burned with sunlight.”

ND: Exactly. And I think being in lockdown has made me realize all those things in my house. Now I know the entire sun path of my flat. And exactly what you said. In the afternoon, it reflects off the building next door and comes in this yellowy weird glow. And you think, “Oh wow! I’ve spent a lot of time in here now.”

How logistically challenging was this shoot in terms of moving from location to location. You’re out in the woods. So you’re not just dealing with bugs and humidity and heat, but you’ve got poison ivy, poison oak, which are prevalent, along with brambles and briars that run around there. You’ve got a swamp scene.

AC: This show is so ambitious, just because the scripts themselves were so dense. When there’s a descriptive paragraph, it’s not just a descriptive paragraph describing something. It’s sort of like saying, “Ben-Hur races and wins.” But what does that entail? Well, it entails about 2000 shots. That was kind of what this show was like. It was incredibly dense. So let me put it this way. When we were in our last four weeks of production, we literally had three units shooting consistently every day. It was that crazy.

ND: Plus the drone unit.

AC: Plus the drone unit. Yeah. We were just having to catch up with all the stuff that we kept on having to put off. We also got knocked out a couple of times with the weather. We’d have these horrific thunderstorms and we’d lose a third of a day of shooting. So just a lot of pick up and catch up. And because we didn’t have a hard delivery date, we were allowed to pick up stuff later. I think the whole production went a few days past what we were originally supposed to go. So it did go over a little bit.

Given the density of this series. I’m surprised it didn’t go over more than a few days.

AC: Yeah. And I think most of those days, if not all of them, were legitimate insurance days because of the weather.

ND: We had a hurricane warning, didn’t we? A couple of days. That was new to me, Debbie. We don’t have that in Britain.

I’m curious, for you, Nicola. This is your first US production. Yes? So, how was the culture shock of a US production with the union regulations? With working with crews here? How was this whole experience for you, and would you ever want to do a US production again?

ND: Yes, that’s correct. I loved it! I mean, it’s always nerve-wracking to go in and inherit a crew, but I’ve done a bit of that before. Alan brought the DIT and the Steadicam Op, I think. So everyone else was from New Orleans mostly. So yeah, it is always nerve-wracking because you don’t know anyone, but they were all so lovely and so good. We have a slightly different system here in the UK, with the grips and the lighting. Grips in the UK, just do everything to move the camera. They have nothing to do with the diffusion or the flagging off of anything. So I just said to the gaffer at the beginning, “Look, I’m from the British system and excuse me if I tell the wrong person to do the wrong thing.” And they were just lovely to me. They were so nice. And I loved it. I thought it was fantastic. I do normally operate because I come from the Australian and British system. So the US union didn’t allow me to operate, which was actually fine, because I could overview everything and really concentrate on the lighting. It is a lot to do when you operate and light. You do feel like you’re going a bit insane every day. But then it was kind of weird to sit in a chair for four months. But I loved it. I really loved it. It did make me laugh, Debbie, that they all called me ma’am, which was very southern, of course. I said, “You can’t call me ma’am. That’s for the queen.” And so I said, as a joke to them, “In England they call me gov’nor.” Well, that was it for the rest of the shoot. They just called me gov’nor with a fake British accent. And then we all got on like a house on fire. So it was brilliant.

Nicola, you couldn’t be working on a project with a more perfect person than Alan, who turned the world upside down with his speech a few years ago on inclusion and diversity. And this marriage here of the two of you just exemplifies and embodies that. And here you are now. You’re jumping into a US production. Thank God you did it with Alan. But I’m curious for both of you about the importance of this collaboration, in these times, in light of what you have been very vocal about Alan.

AC: This was such a success story on all those levels. And I’ve had some good success and not so good success trying to bring in inclusive situations. And it mostly has to do with the short-sightedness, and the blindness from hiring powers. It’s amazing how shortsighted and how closed-minded the people who are responsible for hiring us are, the people who have it in their power to make this industry much more inclusive. Nicole, you brought out probably the best point of what we’re up against when we go into places and hire crews from scratch. Maybe you can elaborate a little more, about your example about the list that we are handed.

ND: I was saying to Debbie, I was saying to lots of people actually, I just want to hire my crew to be a diverse crew. It’s very important to me because I think that’s the way forward and they should be like that behind the camera and in front of the camera because that’s how we tell the best stories. That’s how we progress the business, on the business side of things as well. But I’m always handed lists, always, that are a hundred percent white men. And I always question those lists because it’s not that women aren’t out there, which obviously we’ve heard a lot, or people of color are out there. It’s just that the lists are very traditionally what people have always looked at. So I question every list I’m given, even on this show that we’re on hiatus from, or feature films. Because we had to hire a local crew North of England, I just said, “Well, is there anyone else?” And then they were like, “Well, we don’t know.” So there’s lots of resources. In a way, you can go and look for those people, which is great. It’s just always questioning like Alan did. He said, “Oh, gosh. I’ve been hiring people that look like me. Maybe I should think a bit more about that.” And that’s just what we all need to do. And that speech that Alan made. He knows how amazing that is. But that went viral in my community because all the female cinematographers were like, “This is the most amazing speech ever.” So when I realized I was going to get interviewed by Alan Caso, I fell off my chair.

I love Mandy Walker’s work. And I think she’s very overlooked when it comes to The Academy when it comes to awards. Look at what she did with Hany on The Mountain Between Us. I talked to both of them about the challenges shooting up there in the snow. In lighting snow. It’s almost as bad as lighting humidity.

AC: She does great work. I’ve got to say, her work is really terrific. She’s a real tour de force. I think she’s terrific. She did a western with a director friend of mine, Gavin O’Connor. I forget the name of the western now [Jane Got A Gun] but it was a terrific piece that she did. Westerns are not easy to shoot. I’ve done quite a few of them now, and they’re not easy. And the worst part about a western is that if you want it to really look good, the worse the weather, the better the movie looks. Because that’s where you get all that dramatic outside stuff. But you go through absolute pure hell if you’re out there fighting hail and rain and snow, and the conditions, and dust and dirt. So you go through hell to get your art. And she obviously did her part.

Absolutely. And Reed Morano. For me, her calling card is Frozen River. But where do you see women becoming more of the conversation in cinematography? It just annoys the heck out of me that people are still not looking at women for this job. And this all goes back to Brianne Murphy, the first female cinematographer in ASC, and what she instilled in me.

AC: I think it’s just a point of when they are no longer the exception to the rule, but they’re just a common face on the set, like everybody else’s. The ubiquity is what you want. You want to see women and people of color everywhere filling out the ranks and files so that there’s no longer a reason to say, “Well, they’re unique. They’re just special. They happen to have a special talent, but normally they wouldn’t be able to make it in this business.” That’s the attitude that we get. That’s the reason why you get these people that say, “Well, do they really have enough experience? Should we really be taking a chance on…” Fuck. You take a chance on these young white guys out of college. And giving them an excuse to say to them, when they fuck up, you say, “Well they’re just learning the ropes. They’ll get it once they give them a little more experience.” And if it’s a woman or person of color who made that mistake, it’s like, “Whoa, see, they really don’t have the talent to do it.”

ND: I did a feature film called Pin Cushion that went to Venice Film Festival about three years ago. It’s a million pound film, so it’s a low budget film, and we had a woman of color as our grip. She’s amazing. She’s been in the industry for years and years and she has been grip assisting for a long time, and that’s obviously because of people’s attitudes towards her. I remember I got her CV and I said, “I want to hire Grace” and the line producer said, “Yeah, but look at her CV. She’s not really done lots of bigger stuff for years. Why she’d been doing all these short films?” And I said to him, “What do you think? She’s a woman of color in the grip department. Why do you think she hasn’t got big feature films on her CV?” And he looked at me and he said, “Oh yeah. Okay.” I was like, “So let’s hire her.”

AC: Very good. That’s very good. That’s actually a great argument. And I’m going to remember that. That’s exactly what they always say. “Well, you know why she’s doing this stuff? How come she’s done all these little [projects]. . .” “Well, she’s a woman. What do you think!” Hello!”

ND: And people keep saying she can’t do it.

I see them so often on my end. Somebody only has all these short films to their credit and it’s like, “My God, your short films are so good. Why are you not working on a feature?” And it’s because nobody will give them the chance. It just aggravates me. So Alan, are you ever going to step into the director’s chair?

AC: I did that on Six Feet Under and the reason why I wanted to do it was I just wanted to get my DGA card so that I could go off and shoot and direct second units, which I’ve done a little bit of. But you have to want to be a director. You have to enjoy talking people into something they don’t want to do, which is what a director does. Or try to convince them that what they say they don’t want to do is actually what they do want to do. They’re just doing it to be contrary. Because that’s basically what happens when you’re dealing with an actor. And I love working with actors, but I’m not crazy about working with actors as a director, although my experience doing it on Six Feet Under was a great experience. And I turned out a really good show and they were really happy. They wanted me to come back the next season and do two more episodes, although that’s when I left to do something else. But I’ve got a DGA card, but I have no interest in being a director. And frankly, a director of photography is not entry-level to become a director.

I don’t know why everybody’s expecting all the cinematographers who are successful to then go on to direct. You know why so many of them do it? I’ll tell you the reason why is because when they’re working on a show, TV shows, but also even features, and these directors who come on who’ve never directed anything, the cinematographer basically is doing a lot of that director’s job. The cinematographer basically is doing a lot of that director’s job. And they’re frustrated and they’re seeing this director get all this money, plus all these residuals, which the cinematographer doesn’t get. And they say, “Well, why the fuck am I helping this person do this? I should just be doing it myself.” That’s why you’ve seen so many cinematographers become directors. But I can guarantee you every one of those cinematographers misses shooting. They miss the art form of shooting, but they’re just making too much money as a director. Frankly, sure. maybe I should have done that a long time ago. It sure would’ve been easier putting my kids through private school if I was making more of a director’s money. But I didn’t. It’s a choice I made and I don’t regret it because, you know what, I’m a really good director’s cinematographer. When I come on a show, I support the director. I don’t do what a lot of gentlemen do, especially in series work, where they’re sniping at the directors all the time. Because it’s “Well, this is my bailiwick and he’s just a guest or she’s just a guest.” I don’t do that. I try to incorporate and support directors. And I’m kind of old-fashioned that way, the way that cinematographers have always been with the directors, supporting them and trying to help bring their visual ideas up on the screen.

You came up through the ranks, Alan, and you learned old school and that’s what’s missing today. You brought up a very good point about why so many cinematographers go into directing. I can’t tell you how many directors I’ll ask them about the cameras. They can’t even tell me what cameras were used on their film, or the look or emotion of the lighting design, and say, “You’d have to ask my cinematographer. I don’t pay attention to those things.” If I were a cinematographer working for that guy, it would make me want to go direct because obviously the cinematographer is the one who did everything.

AC: The other thing too, is that because there’s been no sort of apprenticeship, kind of working his way up through the ranks kind of thing anymore like it used to be, you don’t learn. A lot of young cinematographers are really poor management people with their departments. They don’t have any feel or charisma with their crew because they actually don’t understand what the crew goes through and what they have to do. It’s sort of like people who are in management, who’ve never worked on the floor of whatever their company produces. I’ve heard such horror stories about the cinematographers who come out of AFI and immediately jumped into a job. And they’re abusive to the crew. They’re arrogant. They have no idea of how to manage the crew, how to get the best out of the crew, because they don’t even understand the jobs that the crew do. They don’t understand it. And worse than that, they don’t understand how to fix things on the set. They have no bag of tricks because they’ve come out of school and immediately start shooting. All they can do is copy what they see as art out there. They don’t have any life experience. They haven’t seen the world. They haven’t done enough of their own thing to apply. And because they don’t have a bag of tricks because they have no experience, or very little experience, there’s so much today where you have young cinematographers and everybody’s fixing it in post. They shoot basically raw stuff and say, “Well, I’m going to fix it in post,” because that’s also what they’ve learned to do. They learned all the tricks of stuff with all the new applications and stuff you can do on your own computer, can do in the post-houses. So they fix stuff in post. But it’s just like if you’re adding atmosphere smoke on your set. When you have atmospheric smoke, something that’s real on set, that you put into the set, it has a different feel and it has a more organic and fruitfulness to it then if you add smoke in post. Smoke in post is a very two-dimensional thing. It doesn’t build up unless you want to spend thousands and thousands of thousands of dollars painting in the smoke properly. So that’s the difference between fixing things in post or doing stuff properly on the set. The more you would do stuff on the set, the more you light properly. The more you light and fix things on the set, the more organic and the more textural and the better your imagery is going to look. I’m afraid that you have so many cinematographers now who don’t have the experience and who do shortcuts all the way through, that they’re contributing en mass all this material and product out there and the audience is now getting used to seeing that that’s the new norm. That’s what they’re used to seeing. They think that’s what the art is. I think that the art of cinematography is getting degraded every year, more and more. I’ll get off my soapbox now.

Oh no! I love your soapbox. You need to do a presentation to film students.

ND: It’s always surprising that more cinematographers don’t come up through lighting, don’t you think, Alan? I always thought that was strange.

AC: Absolutely, I think some of the best cinematographers are people who are gaffers. We have all these wonderful tools and stuff to fix stuff in post, but you should only go to those things when you absolutely must need to do it at the very end of the day. If production was hampered because of weather or things that just beyond your control, that’s one thing. But to fix normal things, just because you don’t have the know-how, stuff that we would normally think is just simple, fix-it stuff – it’s really gotten to be dire now. You hear the horror stories I hear from directors who tell me, “I was working with a cinematographer who just couldn’t figure out how to do it.” It was a simple reverse or whatever, just simple, stupid things. And they just don’t know how to do it. These are the people who are getting hired.

And these are the people that are the future of the industry. That’s the worst part.

AC: It’s true. I think in management it’s the same thing. You have people now who are heading up the studios who have absolutely no experience in marketing and don’t even know how their own product is being made. They’ve never been on a set, anything like that. And you look at Netflix, you’ve got executives literally going through a revolving door. That’s why they keep on firing and hiring all these young people. Because these people come in, they don’t know what they’re doing, they get fired. B ring in the next lot. It’s like, “Just hire people who know what they’re doing straight off the bat and you won’t have this problem.” This love affair with youth in our industry, which is another problem. Ageism is probably the worst abuse that’s happening in this industry. Much more so than even inclusion. It’s rampant. I’m even guilty of it myself when I hire people. When I hire crew and I see some old guy come in, it’s like, “Oh God, he’s going to bring it all in his fucking closet. Skeleton in the closet. All his biases. He’s going to come in and say, “No, I really don’t want to do this. You know, I just don’t do stuff that way.” Bring me the young person who just is ready to go and ready to do anything. So I’m as guilty as anybody else. I’m terrible. It’s like, I don’t want to see the old guys coming in. And I know that’s true. Because if I’m saying that about people, what are they saying when I walk in the door? Like, “Who wants to hire this old guy? What a jackass.”

So Nicola, now not only do you have to worry about sexism, as you go through the industry, now you ‘ve got to worry about ageism coming up in 20, 30 years.

ND: I know, I know. I think the saving grace for that, is as cinematographers, you can be 70 and still be the oldest person on set. I call it the career that keeps on giving.

AC: Even with directors, they can’t be that old. That’s why I’m desperate to move to Europe because I think in Europe, they respect old cinematographers even more than here.

No, I think you’re right, Alan. This is so wonderful talking to the two of you. For my money, you both succeeded tenfold with PARADISE LOST. I love every episode. I love Nicola’s work and your shooting of the greenhouse, which is stunning. You both capture nature so beautifully. You make me salivate with those flashbacks. And then you throw in underwater photography. But before I let you go, I’m curious what was the best thing for each of you, the most gratifying thing, about working on PARADISE LOST?

ND: I think, for me, I was really quite nervous because, like you said Debbie, I’d never worked in America before. I never worked on a show that had this much money. And so, for me, I was like, “Wow, this is going to be a big learning curve.” But that’s because I always wanted those opportunities. I just didn’t have them. I knew I could deal with it. I just had never been given that opportunity before and I’ve been shooting for 15 years. I’ve been shooting a long time. So to have that challenge met, that I could handle a crew that big with all those [toys]. I’d never had a 50-foot Techno, I’d never had a budget to have a 50-foot Techno crane before. I was like, “Wow! I asked for a crane and I got one.” Normally I ask and they say, “Oh no, no way.”

Every girl’s dream is to ask for a 50-foot Techno crane and get it!

ND: Exactly! I’d been reading a few scripts in America since I had an American agent for about a year. And I think just reading this, I just knew it was a project that I really wanted, that Southern Gothic. It’s so different from anything I’ve ever done and to come to the South and sort of look at the South with tourist’s eyes. Do you know what I mean? You can see it afresh in a new way where I could think, “How are we going to do this?”, and look at the South from a British point of view. I think I said that in my interview with you, Al, didn’t I? I said Frances is a fish out of water and I will be, so, therefore you should hire me.

AC: That was a big thing that Rodes Fishburne and I wanted, is to have a new set of eyes on all this. We thought that you coming in, bringing in a different set of eyes, was going to be vital and stimulating, stirring the pot and getting the mixture going, which is the whole reason for inclusion. That is the essence of inclusion. The essence of inclusion is that I don’t want to be surrounded by a bunch of old white guys that look exactly like myself. Because we all have the same life experiences, we’ve all done the same things in life, and where’s the art in that? You get people who bring in all these different ideas and walks and experiences of life and that’s the way you tell great stories. For me, every so often you just get those shows that come on, that you get to do all the stuff you want to do because you’re in complete accord with the showrunner or the producer or the creative producers and directors. And you get to do all the stuff that you want to do; things that already are in your wheelhouse that you’re good at, but also stuff you wanted to do on other shows and haven’t been able to do. So this is just one of those shows. That’s why, to me, that’s what made this show so great for me, it was all the stuff I wanted to do. And having John Lee Hancock as the first director, who I did the pilot with, he and I, we just saw everything the same way. And to a lesser degree, but not so little also, was with Romeo. Romeo and I saw everything very similar. So it was a good experience. But I just knew that the material is the stuff that I know how to do really well. And I just wanted to do something different with that material that I’ve done with similar material in the past. And so it was good.

I can’t thank the two of you enough. This has been just one of the best conversations ever.

AC: Oh, that’s great. We sure appreciate being asked to do this. That was very nice of you. We’ll keep you posted and seeing what we’re doing. It’s really been terrific. It’s great talking with you.

by debbie elias, exclusive interview 05/13/2020

PARADISE LOST is airing now on Spectrum Originals.