Who else would be the first choice to score a mini-series on CATHERINE THE GREAT other than RUPERT GREGSON-WILLIAMS? To call Gregson-Williams multi-faceted and versatile is an understatement. Capturing theme and emotion in everything from animated films like Over the Hedge and Abominable to tentpoles like Aquaman and Wonder Woman to light romps like Here Comes the Boom or What A Girl Wants to the heartfelt gravitas of a true story like Hacksaw Ridge or Hotel Rwanda or period episodic series like The Crown and The Alienist, there is nothing that RUPERT GREGSON-WILLIAMS can’t tackle or elevate through musical composition. And now he brings a truly musical cinematic presence to HBO’s CATHERINE THE GREAT.

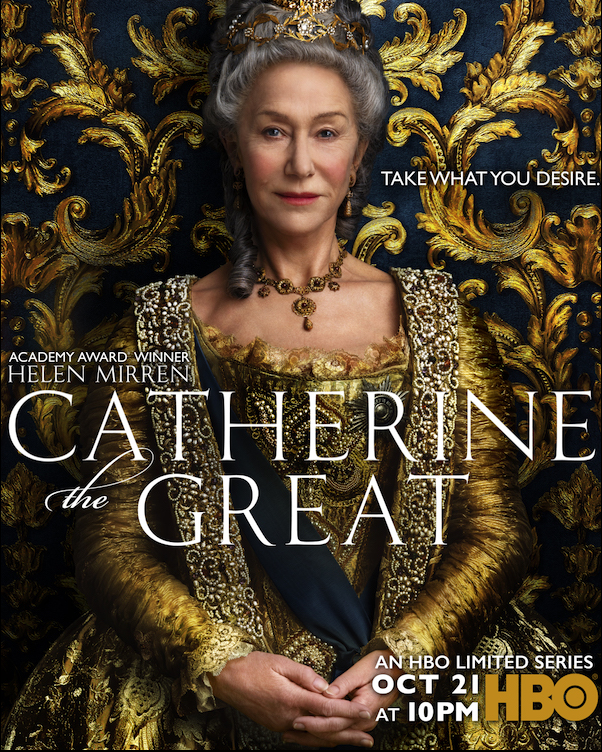

Starring Helen Mirren as CATHERINE THE GREAT, Catherine ruled the Russian Empire in the 18th Century, expanding not only its borders, but its culture, welcoming the philosophy, music, the arts, and even fashion, from Western Europe. This four-part historical drama centers around one of history’s greatest love stories, that of Catherine and Grigory Potemkin played by Jason Clarke, and Catherine’s rise to power after she removed her husband from the throne. Together, Catherine and Potemkin helped shape the future of Russian politics with their like minds and melded hearts. It is their love and melded hearts which are the heartbeat driving Gregson-Williams score through the high drama of politics, battles, family, and love.

Gregson-Williams submitted the fourth and final part of CATHERINE THE GREAT for Emmy consideration in the category of Outstanding Music Composition for a Limited Series, Movie or Special (Original Dramatic Score). And what a perfect segment to showcase his talents as a composer. Keeping the relationship between Catherine and Grigory Potemkin at the heart of the series and the music, this final episode is no different and, in fact, like a fine wine with age, intensifies in its vibrancy and musical color.

Filled with hope, heartache, drama, jubilation, subterfuge, and undying love, every emotion is beautifully felt through the scoring. A powerful and climactic episode that leads us to the deaths of both Catherine and Potemkin amidst a declaration of war by the Turks, Catherine recalls Alexi Orlov to the Council while Zubov is now used to spy on her as her power-hungry enemies loom like vultures, particularly her son Paul. Potemkin is very ill with a virus he caught in Crimea. Knowing her own end is nearing, she tries to keep her grandson Alexander from his parents and grooms him to succeed her. While Potemkin is in Crimea trying to achieve peace with the Turks without bloodshed, he dies. With Potemkin’s passing, Catherine is not only grief-stricken but heartbroken and she dies as well. Against her wishes, Paul succeeds Catherine on the throne but as we learn through the epilogue is that Alexander turns the tables of Paul within a few short years and as Catherine did with her husband, takes the throne from Paul fulfilling his grandmother’s dreams. But one of the most emotional moments of the film comes with a flashback to ten years prior and the wedding of Catherine and Grigory Potemkin. (Always believed to be true that they were indeed married, there has never been any solid evidence to prove it.)

Speaking with composer RUPERT GREGSON-WILLIAMS in this exclusive conversation about his musical approach to CATHERINE THE GREAT, we discuss developing the composition, musical influences, modulation, and instrumentation, finding that balance between Catherine as a woman and her deep love with Potemkin and Catherine as an empress building the Russian Empire, finding the humor of Potemkin and Catherine, and how it all climaxes in the finale episode of the miniseries.

So good to speak with you, Rupert. I have long been an admirer of your work going all the way back to What A Girl Wants. That has long been one of my guilty pleasure films.

I like that movie, too!

Your diversity as a composer is fabulous as you go from something like that to Here Comes the Boom, or The Crown, or the heavy drama of Hotel Rwanda. And what I love with your latest endeavor with CATHERINE THE GREAT is that I see all of these colors and textures that I’ve loved over the years from you, all come together here. This scoring is so cinematic, Rupert, so rich, so textured. I’m curious as to your approach with this one, given it’s a limited series. You’ve got four episodes and they span many years and much change geopolitically, culturally, and emotionally. Where do you start when you have the power of the story of Catherine and the power of Helen Mirren. Where do you begin musically?

Well, you’re right. It’s a rich subject and so I spent a lot of time talking to Philip Martin, the director, who got this show on the road with Helen. I had worked with him on The Crown so we had a relationship anyway. He was always the one on The Crown that I used to talk to the most or, at least talk with in an academic way about the story. So when we both left The Crown and went on to other pastures, he asked me to do this. One of the first things he asked me to do was to read a couple of books and some articles on Catherine. I didn’t need much pushing really, because I’ve got to be honest with you, I didn’t know much about Catherine. I knew that she was German and I knew that she overthrew her husband and that’s about it. She was friends with Voltaire and she brought philosophy over from France. She invited composers over from Vienna. And she admired all the Western arts or Western European arts. So that’s where I sort of started and realized that actually the Russian music, the musical sound of the classical musical sound, was very Viennese and Parisian and German. It didn’t have that sort of passion that Russian folk music has or the Russian music that we know from the 19th century, going from Tchaikovsky straight up to Stravinsky. So I then went digging into more of the liturgical music and the folk music which is where I found some lovely colors, that sort of passionate Russian sound. Then I brought my own, I hope, sort of the modern sounds that I used which weren’t deliberately used or forced onto it. It just felt natural to bring it up to date a little, or to make it feel contemporary.

That’s one of the beautiful things that I love her and it’s because Catherine was so renaissance in her thinking and in embracing everything so culturally. It lets you bring in during the balls, Viennese waltzes. And then you have a lot of whimsy when it comes to Catherine and Potemkin, particularly in episode one, the stairway scene, where he is singing and you really bring in some beautiful notes. The tinkle of the piano and a whimsical tête-à-tête. And you carry this through, almost as a motif, with strings with Catherine and Potemkin throughout all four episodes. Great use of strings throughout all four episodes.

The violin I use, I actually recorded a lot of it before I really recorded or wrote any of the rest of the score and put it into my armory, just lots of little patterns that I had the violin player play, and I played a few bits and bobs too on double basses and cellos and things. They were quite useful in driving the story along. I always find Catherine and Potemkin’s relationship had lots of humor in it, especially Potemkin, so I use this sort of solo violin ostinato to represent his humor and good nature. Then obviously to the other side of it, Helen [Mirren] had this idea right at the beginning that she wants to sort of play it like Obama but by the end, she’s playing it like Mugabe. So you have this sort of “weight” that you can put in there. I use it with low brass and percussion and a low choir and all sorts of modern synths and things. So it was a really good fun project to do and I bet you don’t often get this sort of time to do something like this. When Philip first asked me to get involved he was still developing it, he hadn’t shot it yet, and I’d read the scripts and talked to him and did some reading and then started writing. So I’d already written about two hours of music before he even gave me a frame of edited footage, which was really nice because I’d already had a chance to get into the world rather than that sort of rushing into it, “now write, you’ve got 10 weeks”. This one I probably was on for about six months on and off. It’s good when you get that opportunity.

A lot of this composition also involves modulation of your tempo and your volume with crescendo and decrescendo. So I’m curious, did you write that into the composition? Or is that something that was worked out in the orchestration and then with the sound design?

I think I probably wrote it in quite a dynamic way so as we recorded it, or as I played it, or as I programmed it, whichever way the instrument was conceived, I think I wrote them with these volumes. It just helped a lot with the drama, pushing the drama from one stage into another because some of the drama actually wasn’t very fast, but really needed to get some story between Potemkin and Catherine, so I’ve sort of tried to use the music to push our story along a little. Also, that Russian passion that you get, I get that from the choral music that I listened to. And that, from very, very quiet, to very, very loud, really appealed to me. I will say when I recorded it, I kept the edges a little bit. I kept some of the edges to it. Sometimes you spend a lot of time producing things to feel really finished and polished, but I kind of left some of the rough edges on with the vocals and some of the violin playing because it just brought a bit of character to it, I felt, and a little bit more authenticity to it, rather than a big polished score.

I’m curious about your use of percussion within the context of this story. I detected that every time we’ve got the rioters, the people, the rabble-rousers, and we hear more of it come in, but you’re also using it at certain times as threads for not only drums of war but also a heartbeat. So I’m very curious about the introduction of percussion and your use of that.

Well, like I’d said before, it was pushing the drama along. It’s quite nice to give it a little bit of a pulse. Also, in other ways, using a pulse between Potemkin and Catherine, when they’re far away she’s writing him letters, I’d just do little pulsing moments to represent that they’re yearning for each other. It’s interesting you noticed the percussion. I had some live field snares and field drums that I did, and for it, my very clever assistant as well. Other than that, there was some use of electronic percussion as well, just to keep the edge going.

What was the most challenging aspect of scoring for CATHERINE THE GREAT?

Interesting question. I thought Catherine has two sides to her. She had a very humorous, deep love affair with Potemkin, and that for me was the whole story really. But Philip was always bringing me back to the idea that we are talking about an empress who started to build Russia into a big empire; so trying to get inside that, trying to make the tenderness between Potemkin and Catherine, but also to represent her as actually quite, by the end, a brutal dictator. Toward the end, in episode four, I’m dealing with the sensitivity of her losing Potemkin, and of her dying. To me it was deeply emotional but at the same time she has become a wicked dictator in many eyes of the Russian people. So I guess that to make us care toward the end, but also to show more how she’d become brutal, that was difficult.

Then of course you add in her wonderful, loving son, Paul, who isn’t concerned about his mother dying on a floor and is looking for paperwork, so you get his frenzy tied in there too. I thought that entire final sequencing in episode four was exquisitely done, Rupert. So well done musically.

That was great! I really enjoyed writing that. I kind of wrote the moment that she died or, in fact, she has died and her grandson sees her son not caring and rifling through papers. I played it quite badly on a broken piano, just a broken piano, and that moment was quite an emotional one. I enjoyed doing it. It was just one of those moments when you play rather than you write, and I always find if you can play the piano or if you can sing – I play a few instruments quite badly – but if I can actually get to be playing it for those moments of emotion, you can squeeze more out of it than just writing and having somebody else do it. But that moment was the broken piano sitting in my hallway of my studio here.

by debbie elias, exclusive interview 07/05/2020