BIRD BOX. Riveting from beginning to end, Academy Award-nominated screenwriter ERIC HEISSERER (“Arrival”) and director Susanne Bier deliver a tension-building thriller that bodes not only one of the most exquisite cinematic payoffs but one of the most powerful emotional journeys of a single character to come along in many a day. Adapted by Heisserer from the acclaimed 2014 novel by Josh Malerman, BIRD BOX takes flight with the very human storytelling of director Susanne Bier while elevating and immersing the experience through sound and sight, and the absence thereof, creating a dystopian world filled with an uncertainty of what’s happening and what’s to come, and an unfolding of events through interwoven storylines of past and present which is both fascinating and frightening.

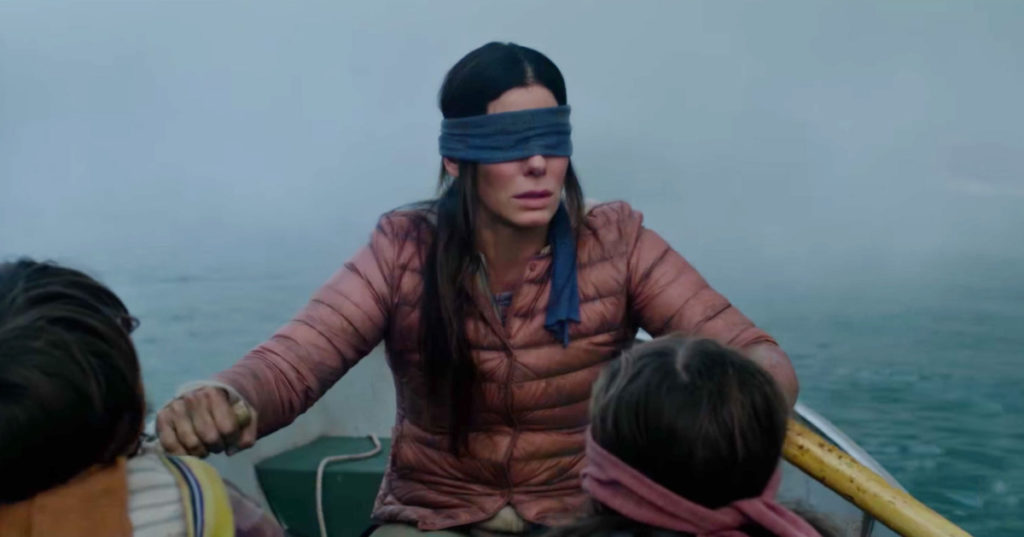

An unknown malevolent entity is infecting the world. Although “invisible” to the naked eye, when an individual looks directly at this unseen being, it causes one to see their greatest fears and commit suicide in the most violent and gruesome of fashion. Seen through the eyes of Malorie [Sandra Bullock], the story spans five years and is told via two timelines, one starting in the present and the other in the past, which as they move towards intersection over days, weeks, months, and ultimately years, builds tension and fear, playing on the Hitchcockian ideals of the unseen or unknown being more frightening than the known. Heisserer has artfully crafted a tapestried script that speaks volumes about each character, the world in which they inhabit, and the challenges each faces individually and collectively, even when we are met with nothing more than silence.

Heisserer is no stranger to the written word. An Academy Award nominee for Best Adapted Screenplay for “Arrival”, Heisserer is also responsible for the thrills and chills that unfold with films like “The Thing”, “A Nightmare on Elm Street” (2010), “Final Destination 5”, the positively frightening “Lights Out”, and of course, the tension-fraught terror of a father trying to save his newborn daughter during Hurricane Katrina with “Hours”, which also marked Heisserer’s directorial debut and one of actor Paul Walker’s final films. One of Eric’s greatest gifts as a screenwriter is his ability to delve into not only the human condition complete with its frailties and insecurities, while tapping into the courage and inherent nature of survival, as well as the best and sometimes worst of humanity. He reframes the language of how we look at things, going deep within his characters and the situations at hand. As we have seen with his adaptations of other works for films like “Lights Out”, “Arrival” and now “Bird Box”, Heisserer always bring added elements of depth and texture to the cinematic canvas with the language of communication as the connective tissue of the story.

It is always a joy to speak with Eric and this latest conversation and exclusive interview talking about the language of BIRD BOX was no different . . . .

Eric, this is outstanding. You had me on the edge of my seat. This whole concept of not being able to see the entity, but then the messaging that we get by the end of it is that you see with the other senses and see with your heart – just exquisitely done. But the real strong suit here is your character development. This is one of the strongest characters you’ve ever written, Sandy’s [Bullock] character of Malorie. I have never seen an arc and a growth in a character like this. I’ve read the book and Malorie is not as strong in the book as what we see and feel on film. How did you go about approaching this and really digging into that character of Malorie to develop and deliver her full-circle? A totally new person comes out on the other end.

Yeah. Absolutely. That was like the best arcs are transformative. I tend to try and write protagonists who are better than me as people. There is sort of an aspirational quality that I can try and reach for. My connection to Malorie started with the thoughts that my wife has about motherhood and about either fears and hopes that are tied up with that. But I really think the script and the story of Malorie evolved when Sandra Bullock came on board. Sandy had very insightful experiences and thoughts and feelings that grew the dimensionality of the character and allowed me to rewrite and sort of the spoke version of Mallory just for her. And it all comes down to that idea of [being] in a world where our trust has eroded so horribly, and especially our trust in ourselves, which is one of the biggest arcs for Malorie, that learning to see a new version of yourself, learning to have faith in yourself in a new way, is the way that we get through these things.

And of course Trevante’s [Rhodes] character of Tom and this whole idea of self sacrifice out of love; we don’t see this enough, Eric.

No. Everyone’s motivated by selfish stuff.

After you read the book and they said “Hey Eric, we want you to write this”, how was the approach to this one in comparison to some of your prior endeavors?

It was still a battle. I mean, it was, the industry term is “a bake-off.” There were several other writers that were vying for it and I kept swinging my heart out for it. I don’t know how many pitch meetings I went in to try and continue to convince them and it wasn’t until I started just writing sample pages and I wrote essentially the opening set piece, where she’s counting out to herself the number of steps she has to make in order to get to the various places and what she says to the kids and the toys that they bring with them, all that kind of stuff, to give a sense of just how the look and the feel and approach should be. I think that’s really where I got them and they felt much better as soon as they got that first draft and realized that there’s a legitimate movie here. It’s hard, I think, when you read the novel to know if you can cinematically express a villain that you never can see and you never should see. But it’s what made me so excited and there are plenty of ways that I think you can begin to exploit that in film.

We see that beautifully done here. I’m curious how you went about tackling dialogue and tackling the descriptive nature of the exposition within the script with a villain that we do not see but can only experience from a sensory place, from the different senses. If your hearing becomes acute enough you can hear. You can feel the leaves, you can feel the rustle of the trees in the wind.

Right. You do feel almost a physical presence ’cause obviously interacted with the car that way. I would say that the revelation for me about this was anywhere I felt I had an opportunity for exposition I also had an opportunity for character because everyone in that house stuck there together had their own perspective on what it was that was killing everyone. And that perspective came from their background. It was a spotlight on who they were as a person; who ran to the sort of religious aspect, who thought it was biochemical warfare, who thought it was the government or one faction that was doing it.

We haven’t eliminated that possibility yet.

No. And none of them are really eliminated and they shouldn’t be, but there was plenty there. I think that some of that got condensed in, of course, the final cut of the movie so that it’s basically the Charlie character who delivers a whole bunch of options. But in plenty of iterations of the script you had everybody who got together around the fireplace to talk about what they think is really out there.

I’m curious how you create a fully sensory experience on the page, because you truly do. Granted we’ve got Susanne’s [Bier] incredible visuals and she just upped her own game with this while staying true to her core storytelling of the human condition and character and survivability. She just upped her game with the physical aspect of this film. But I’m curious because of the sensory nature of how this story is told, did you incorporate that into the script, such as when we’ve got Malorie and Tom and they’re blindfolded and they’re outside and they’re scavenging houses and trying to get canned goods and food or clothes or toys. Was that something that went into the script or was that just something that became inherent in Sandy and Trevante’s performance and in Susanne’s direction?

Oh, yeah. It’s still definitely a Susanne Bier film! I had a lot of fun with the script on this one and I try to be as evocative as possible especially when it comes to characterization. Like in the supply run, everyone had their own version of a blindfold. Felix had a motorcycle helmet that got blacked out. One of the other characters had a sleep mask. Someone else had a bandana. It got to be sort of an indicator of who they were as a character. And their approach to doing something as a group had to be very sense oriented. But I think that the experiment on this script, and I don’t know if anyone will get a chance to see it just because it’s always sort of a blueprint document for the actual final product, but I was aware of the experience of being with Malorie and the two kids by themselves and then the experience of everybody crammed into one house together. I was looking for a way to subtly even represent it on the page. So I gave myself some boundaries so that any time we were on the river with Malorie I could only do 100 words for that page. It had to look like haiku. It was a whole bunch of white space to evoke the idea of silence and loneliness and tension. Whenever we got into the house, which was noisy and crammed with people, I started doing dual dialogue. I went large with blocks of text to give you a crowded sense of sort of a claustrophobic nature and tried to sort of design the script to let you know how the feel of the movie would be.

You typed it visually! That’s so cool. I love that, Eric.

I did. I don’t always do that but I did it with this one. It’s not that anybody else gets to see it but . . .

But as I’m watching the film, I can see that with the dialogue on top of dialogue and everybody talking over everybody else and then the silence and that silence is deafening even though you’re hearing a roar of the rapids and the river. It’s the silence.

Oh totally. No jets overhead, no car sounds, no other … nothing.

I can just imagine looking at this page, I really can, because that’s exactly what the screen looks like. Amazing. Something that I really appreciate with this film and with your script is the fact that with the superfluous supporting characters you don’t give any of them the short shrift. We actually get a full story with each one them as to who they are. You didn’t go with the expected tropes like, any time you have a horror movie or a thriller movie the black guy is the first one to go. That didn’t happen here. You really bucked the system with a lot of this. We didn’t even have annoying Olympia [Danielle Macdonald] go out first! Then we get Tom Hollander as a seemingly bland supporting player but he turns out to be anything but. How fun was it for you to be able to really craft out each of these people? Not just your leads but everybody so we actually know everything about their lives.

It was a real challenge because you really want to make sure you spend time with characters that you know you won’t get much time to spend with later on because they just aren’t gonna make it, and if you don’t deal with them early on then they don’t have a chance to sort of shine. But at the same time, this is Malorie’s story so you don’t want to pull too far away from her. Her transformation is so important in this story. It meant that we had to be as economical as possible with those other people and understand them in a heartbeat. What I did was I just overwrote those characters and gave a whole bunch of extra pages. In fact, when you do sides for auditions there are scenes that aren’t going to be in the film but explain more about them and in hopes that you get to pick sort of a greatest hits at the end of the day when you’re in the editing room. It’s like, “Okay, what’s our favorite moments here that continue to zip, land it in?” There had been some dialogue between one of the other residents and Lucy [Rosa Salazar], the Academy cadet, that was basically “Are you with the neighbor’s landscapers?”, and she’s like, “No, I live here!” and it’s that prejudice that you can lean into. It’s about reframing the way we look at things so, of course, you have to do the same thing to your characters.

How long did it take for you to draft this script, the first draft?

The first draft, 40 days.

How long did it take you to polish it up?

4 years.

I was going to say, this is not a 40-day script.

No, but I was just, full head of steam so passionate about it. Got a chance to talk with the author a lot.

Is that helpful for you to talk to the author as to their original intent and what they see?

Oh, sure. I am, maybe at the frustration of the studios, I am first responsible to that author’s message and to their material. I don’t ever want to betray them in whatever it is, be it the spirit of their project if not the letter of it. So, having a good relationship with Josh on this was vital.

I’ve got to ask you about writing for “Boy” and “Girl”. It’s never easy writing for children. It’s even more difficult, I imagine, writing for children who spend much of their appearance blindfolded and who have not had the chance to interact and really develop verbal skills with other people. How did you go about creating the empathy that we feel for them?

Well, in the script I gave them a home-brewed special language that’s sort of a Morse Code they can learn from each other that they do it by touch. So that when they are close they just do this [demonstrating a two finger tapping] and they tell each other something. So, that helped me into the insight of the world of these two and it allowed me to grow out their characters a little bit more from just a single communication style. I gravitate towards interesting languages.

What did you take away from this one, what did you learn with crafting this script? I know what all you took away from “Arrival” and how close that was to your heart with language and your dad. So I’m curious what did you take from this one that you’ll now take forward?

I think it’s that if anyone is gonna save the world it’s women.

by debbie elias, interview 12/04/2018