Focusing on a specific event which occurred on September 5, 1862, when meteorologist James Glashier “hitched a ride” in a balloon belonging to aeronaut Henry Coxwell, with THE AERONAUTS director TOM HARPER fills us with all the wonder – and fear – that Glashier and Coxwell must have felt as they ascended to the heavens, going higher than any aeronaut had ever flown and opening up new meteorologic wonders to scientist Glashier. Coxwell had been working as a balloon taxi-service for Glashier since 1860 with Glashier always the passenger along with his multitude of weather measuring devices, and in this instance, pigeons. Travelling more than 37,000 feet – about seven miles – up into the air, the two not only suffered balloon sickness with Glashier passing out around the four mile mark, but the valve that would allow the balloon to descend was caught amongst ropes and ice formations on the balloon due to the frigid air temperatures. Coxwell was forced to climb out of the balloon basket and up onto to the balloon in order to release the valve. History documents that Coxwell used his teeth to release the valve.

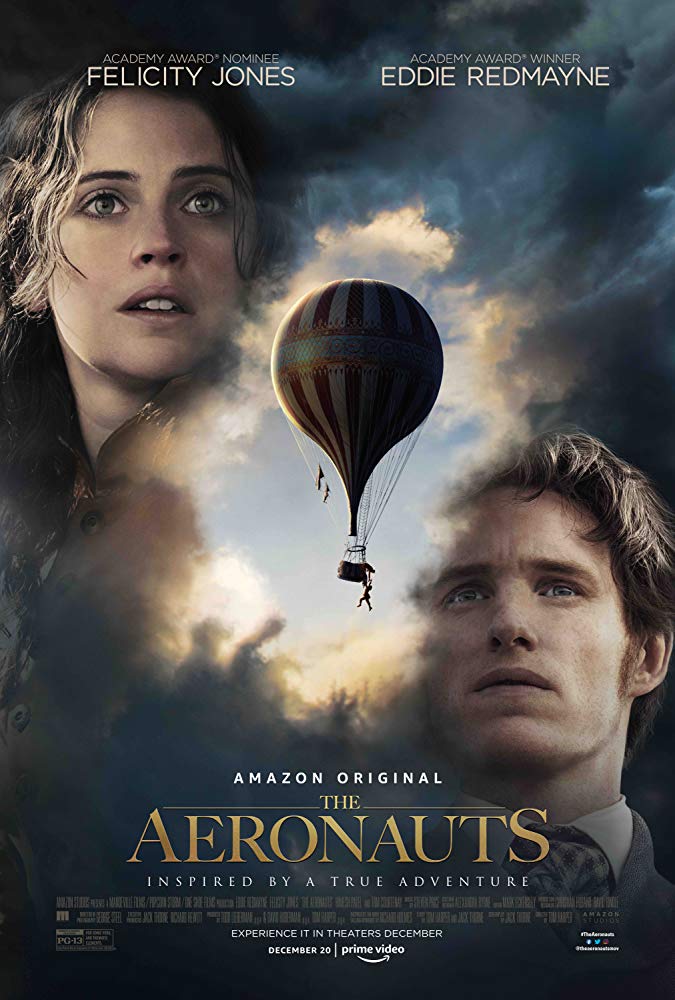

As if just reading about Glashier and Coxwell and this September 1862 adventure isn’t exciting enough, producers Todd Lieberman and David Hoberman team up with director Tom Harper and writer Jack Thorne to bring this story to the silver screen. Taking some literary license with history and replacing Coxwell with a female aeronaut named Amelia Wren, the story opens up with some added themes of feminism that are as timely today as in 1862, and it allows for a reteaming of Eddie Redmayne and Felicity Jones as James Glashier and Amelia Wren, respectively. The story is just as exciting, and perhaps even moreso, with Glaisher and Wren over Glaisher and Coxwell. Calling on the collaborative talents of cinematographer George Steel and VFX Supervisor Louis Morin and his team, from the beauty and the fury of Mother Nature to dancing yellow butterflies 20,000 feet up in the air to the whispers of snowflakes, to the unfiltered warmth of the sun, to the crystalline clarity of twinkling stars on the rich blue-black canvas of 37,000 feet above the Earth, this is the adventure of a lifetime and one of the most beautiful and visually exquisite films of the year. THE AERONAUTS is a true cinematic experience!

Perhaps known best up to this point for his work in television with series like “Peaky Blinders” or mini-series like “War and Peace”, Harper also delivered the dark and chilling feature film “The Woman In Black 2: Angel of Death”, and “War Room” written by Jack Thorne who again reteams with Harper for THE AERONAUTS. But 2019 is proving to be an exciting cinematic year for TOM HARPER thanks not only to THE AERONAUTS, but also the critically acclaimed “Wild Rose” starring Jessie Buckley.

I spoke with TOM HARPER in this exclusive interview talking about THE AERONAUTS and taking flight with sight and sound to create not only a unique immersive moviegoing experience, but to tell the story of this epic journey in history through flawed and fascinating characters. . .

This is one exquisite film that you’ve put together here, Tom!

Thank you very much.

You mesmerize with the visuals of this film and all of the thematic elements that you bring in deviating from the original story of September 5th, 1862, when Glaisher went up with Henry Coxwell. I’m curious, what led to switching up the facts of the actual event, replacing Coxwell with a fictional character of Amelia. Was it so that you could then take it further with themes?

I think it came out of the fact that the first flights I’ve read about was this one in 1862 and it was such a remarkable feat that I thought well, that would be a good thing to finish around once they achieved this amazing thing. But during the duration of the fight they didn’t really speak to each other because they were so busy taking measurements. So whilst that was sort of amazing and admirable, two people sitting in silence for 90 minutes in a basket obviously doesn’t necessarily make the greatest film. So, at that point, I realized that we needed to bring in elements, either from our imaginations or from other flights, and I started reading about other flights and other sorts of extraordinary things that happened. It meant that we sort of formed an amalgam of some of the remarkable things from a number of different flights and in that way, sort of created this extraordinary journey, epic journey in the skies, that drew from all sorts of amazing and inspiring people, characters, and events. Because I knew that we had to bring in different elements, I started thinking rather than just having two people who are reasonably similar in a basket, who would be the most different person to put into the basket with James Glaisher? And there was this fantastic aeronaut called Sophie Blanchard who I was really struck by. [She] was a sort of flamboyant firecracker of a woman who did acrobatics, who would set off fireworks from her basket in the air, and go on these night flights. And, so I thought, “Well, if you put her, who’s all about instincts, and James Glaisher, who’s a meticulous scientist, into the basket together, then you would get a really interesting character dynamic. So, that’s sort of how it came about.

It truly is an interesting character dynamic. It works so well. I’ve got to ask you about reteaming with George Steel, your cinematographer, and creating the visual imagery here. What the two of you have done visually, and then adding on some VFX on top of that, is just outstanding. I’m curious how you went about designing the visual tonal bandwidth, taking us up into the sky with the incremental footage which you employ, but then capturing the atmospheric bands of pressure and visualizing the stratosphere and the skyscape for us. We’ve never seen that in a film before.

I think that’s one of the things that really appealed to us about making the movie, and it sort of all came from story and from reality really. We wanted to give as a realistic depiction of what it would feel like to be in the air, as possible. Now, of course, I guess we’re one level above reality in the sense that we go to some of the most impressive things that you might see all in one ride. But, our starting point was reality and, if you were to be on that flight, what would that experience be like? So that sort of led us to building a balloon to try for real, just sending up all our ATDs (Assistant Technical Directors) in the balloon to experience what it was like for real, shooting Eddie [Redmayne] and Felicity [Jones] 3,000 feet above London in a helicopter whilst they filmed some of the scenes, to sending a stuntwoman on the outside of the balloon as she climbed up 3,000 feet above the British countryside. And then we were able to take all of that and then put it into this stuff that we couldn’t do for real, and use those experiences. But another sort of key thing to George and my sort of concept was in the vein of keeping it as real as possible. Every shot had to be possible to either shoot from a helicopter or be in the basket. So the idea was there’s almost like another character in the basket if you like, which was George. And that forced us onto wide-angle lenses and a lot of the kinds of stylistic decisions were therefore made as a result of, if we were going to do it for real, how would it be done?

I know that for producer Todd Lieberman, authenticity in his films and doing things as practically as possible are his watchwords. Something else that we have also never seen before is the balloon that you had built. It is actually a gas-operated replica of those flown in the 1800s. Anytime we ever see balloons in films, they’re always just current day hot air balloons. What was the significance for you in making sure you had the gas replica?

It was pretty fundamental really. You couldn’t have taken a hot air balloon to that height, I don’t believe. And the fact that all those balloons at the time they flew up in were gas balloons, it felt very important to replicate it. But also there’s a different feeling to them. They’re piloted differently and there are subtle differences in the flight as well. The fact that you don’t have the kind of constant burning, which is very loud, gives a serene quality and you really do feel like you’re escaping the world when you go up in them. And that’s sort of something about what the film’s about. It’s about these two characters trying to escape their lives on Earth and, through their relationship with each other, they sort of discover their place back on Earth, and part of that is about their escape. It’s all the subtle stuff. I think that in filmmaking in general, but certainly with this, it’s the small details that make it, that make all the difference. There’s that last two or three percent of the visual effects that’s the details or because the performers have actually experienced what it’s like to fly. They went to those lengths to kind of get their performance over the line. It’s the kind of the physical extremes that Felicity puts herself through that help us deliver, that really physiological, powerful physical performance. So all of those little details and trying to capture things for as real as possible made all the difference, I think.

Another thing that makes the difference with this film is your sound design. This is one of the most unique sound designs I have heard. We have periods of silence, we have the echoing reverberation from 2,000 feet down, 20,000 feet down on the ground. It’s absolutely stunning. How did you work with your sound designers and your mixers in coming up with this beautiful sonic scape for us?

I think it’s a gift of a film for that, actually, and I knew that it was always going to be a real opportunity here. Lee Walpole came on the set and the supervising sound editor came on very early, in fact. We spoke right at the beginning about ensuring sound, so even before we’d started filming, he went up in a hot air balloon with Tom Williams, our sound recordist, and they recorded a whole bunch of stuff from a real flight. He was involved in soundproofing the basket because obviously the wicker baskets creak an immense amount, but just really getting a sense of what the reality was and then building it. But there were lots of challenges actually because we had to give the sense that the balloon is moving through space at the same time as catching the silence. So it really was carefully crafted through all sorts of very small sounds really; like the tinkling of instruments, the sound of the flags moving through space. Another thing about balloons is that the movement comes from the balloon going up and down. That’s where the wind comes from because they’re moving at the same speed as the wind. So it’s very particular, and then the sense that, because it’s a balloon, it’s in three-dimensional space, so you can really hear what’s below you in sense of the ground and above you in terms of the balloon. So all those creaks, that rigging and the ropes, presented a real opportunity. And then there’s, of course, the storm and the falling, the descent. There was a lot of work went into it.

by debbie elias, exclusive interview 11/18/2019