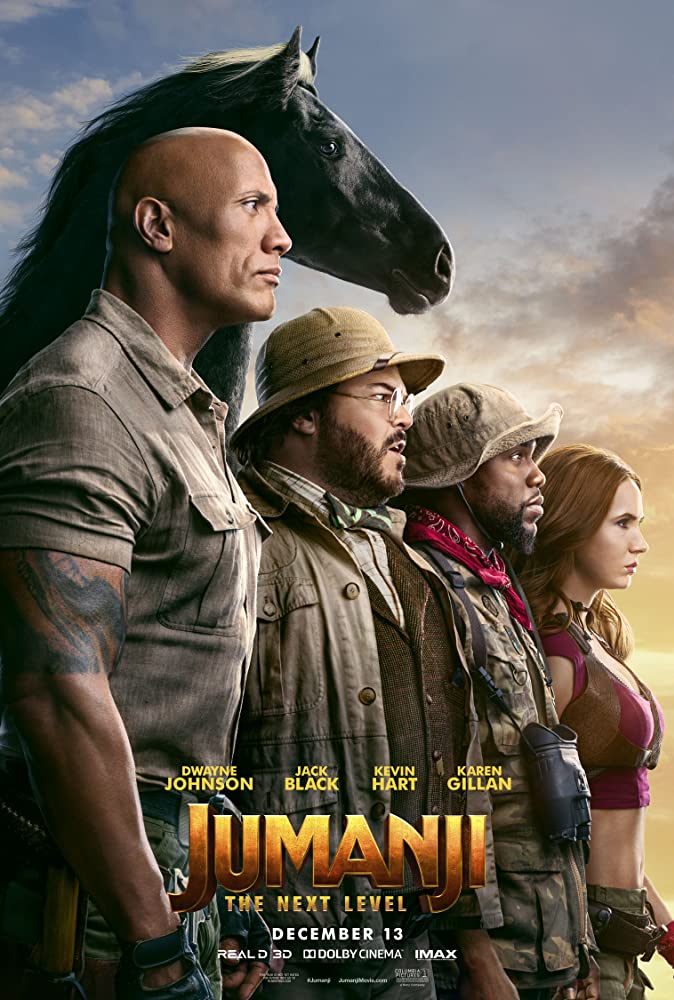

When it comes to digital effects, Weta is at the top of the list. Innovators and pioneers, no matter what the film, the artisans of Weta Digital always seem to push the envelope a little farther, taking it to “the next level”, challenging technology and their own creativity. We saw it with the reboot of the Apes franchise. We saw it with that explosive third act climactic “Avengers All Assembled” sequence in Avengers: Endgame. Weta had us doing double-takes with Gemini Man and a 100% CGI Will Smith playing opposite himself. And now we see their expertise and excellence again with JUMANJI: THE NEXT LEVEL.

Just as JUMANJI: THE NEXT LEVEL raises its own game with story, action, and adventure, so do the CGI needs in order to execute and deliver on that story. And this is where Weta Visual Effects Supervisor K EN McGAUGH and his team come into play. A two-time Academy Award winner, Ken has spent his career in visual effects, first at Weta working on the character of Gollum in The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers and The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, then jumping over to Double Negative for a decade working on films like Batman Begins, Avengers: The Age of Ultron, and Godzilla, before returning to Weta Digital as Visual Effects Supervisor on Alvin and the Chipmunks: The Road Chip, and The BFG. And now he tackles some of the most intricate visual effects of his career with JUMANJI: THE NEXT LEVEL.

While there are several effects houses involved in the film, it fell to Weta to handle the mind-blowing rope bridge sequence complete with bridges, mandrills, digi-doubles, live action, rapid-paced three-dimensional action, and then dazzle us with some terrifying hyenas. For my money, the award-worthy work of KEN McGAUGH and Weta Digital with the rope bridge sequence is a big reason to not only see the film, but see it more than once.

Chatting with Ken during global pandemic lockdown, we not only spoke in-depth about the effects process for JUMANJI: THE NEXT LEVEL, but the current production situation around the globe. While the whole of Weta is “working at home right now and all efforts are in maintaining business continuity for the current projects, the big fear is because you can’t shoot. Without the ability to shoot, you don’t have to edit and without the ability to edit, you don’t have ability to do visual effects.” As Ken notes, as long as the world remains on lockdown, even productions shot in New Zealand where Weta is located and where so many productions now shoot, are crippled because “we won’t able to import cast or crew like we often have to.”

While Weta Digital and Ken and the world await normalcy and more movies in the production pipeline, it does give us time to view the films that we have available now for screening and appreciate the work of the artisans who brought those films to life; and one of those is KEN McGAUGH and JUMANJI: THE NEXT LEVEL. From 200 to 300 mandrills, 100 to 200 suspension bridges, an exquisite topographical backdrop, and beautifully composed and balanced foreground and background, Ken and his team left no stone unturned, no mandrill left hanging. . .

Ken, something that I’m very happy about is that you were with Weta, you left Weta, you came back to Weta and now you just worked on one of the coolest cinematic sequences in JUMANJI: THE NEXT LEVEL. I’m watching the film and the bridge sequence comes up and I’m immediately thinking of is MC Escher and that famous drawing of his with all the staircases, and Hogwarts with the moving staircases. Floating in air, going back and forth; it’s not one-directional. Everything is very volumetric in three dimensions as things are moving. You bring in rope bridges that are breaking with weight and you’ve got the weight of somebody like Dwayne Johnson that’s going to have a different balance and then counterbalances with somebody small like Kevin Hart. This sequence is masterful.

Well, thank you. I like your MC Escher reference because that’s the one thing that we actually had not really thought about, but the Hogwarts staircase shots were something that was on our mind when we’re looking at some of the shots with the counter-rotating bridges, just as a sense of vertigo and chaos. But, it’s meant to be confusing. In some ways that actually helped us. That meant that we didn’t have to maintain strict continuity and it was trying to maintain strict continuity in some situations because we didn’t want the audience sitting on what happens in what order and we just wanted them to be as confused as it was meant to be.

That’s what the whole idea of Jumanji is. The game is confusing and it breaks the rules so there are no rules.

Exactly. Definitely. We’re very, very proud of the work. They obviously came to us because we have a little bit of experience doing monkeys. So by the end, we had wanted a big shot, and it was really coming together and Mark Breakspear [VFX Supervisor] had commented how great the bridges look. He’s very, very witty and he made a joke about, “Well, that’s why they came to Weta because they’d come for our bridges.” Well, the bridges were secondary. But to be fair, the bridges actually ended up being less as much of a character in the sequence as the monkeys and technically a lot more difficult because we were used to doing monkeys and hoards of monkeys. We don’t have a lot of experience doing something like rope bridges, especially given they have to work with a hoard of monkeys. It’s animation on top of animation on top of animation and that broke all the assumptions our pipeline makes and we had to invent new ways of working to do it. It was a bit of a gamble but it really paid off at the end.

Something that I found particularly striking is the layering that you have here. You’ve got the gorge itself, you have thousands and thousands of green plants, you’ve got fog, you’ve got mist, you’ve got volumetric clouds coming in, you’ve got monkeys; Mandrills, which are very different than gorillas in many respects, and you’re making them mean and nasty and mandrills are not mean and nasty primates. So, you’re just building and building. And then you’ve got stunts happening so you’re doing digi-stunt doubles, I’m sure, and digi-principal actor doubles. So, this is just layer upon layer, upon layer and then all of that’s thrown on top of bridges. Where do you start with something like this?

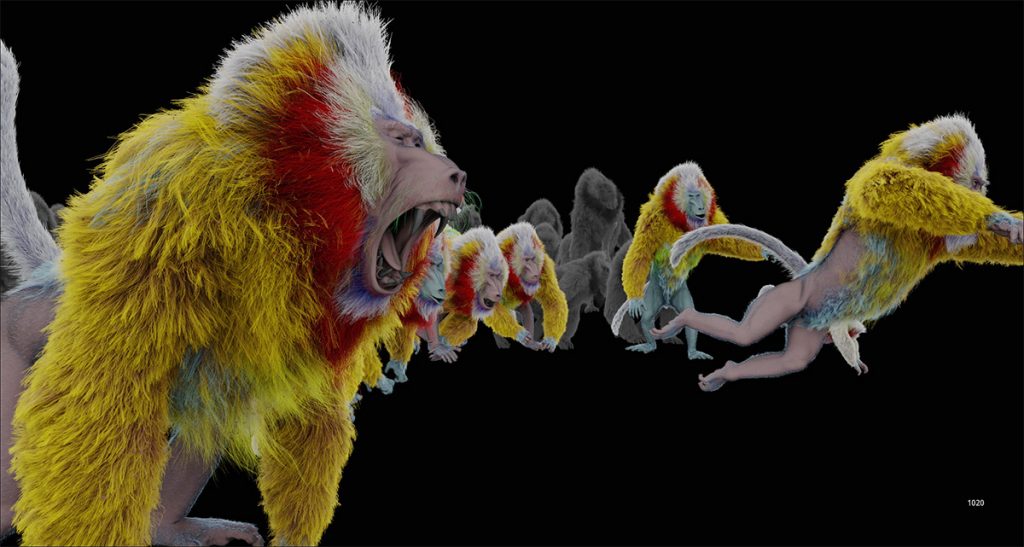

There’s two places to start. The first place is when it comes to the monkeys themselves, we just look for reference. As you mentioned, mandrills are not very aggressive and we could not find any reference of a mandrill being aggressive. A lot of the aggressive behavior and looks we had to model up from the baboons or other monkeys. So, there’s an extrapolation there. To those people that know primates, the first thing they’ll probably notice, I’m sure there’s some forum somewhere where someone’s had a winch about this, but our mandrills had tails and real mandrills don’t have tails. In our video, mandrills, they’re meant to be scary and they’re meant to be different so they’re actually not anatomically correct to real mandrills. But the main place we like to start, and we prefer to do this whenever possible is, we like to start with principal photography. Even if we ended up replacing pretty much everything in the frame or CG, it still really grounds the work, having something to base it off and if incorrect, they can remove little bits of the set or environments they didn’t match to. Unfortunately, there’s lots of photography in there. It’s all blue screens so we have tried to replace quite a bit of it with the environment. But that really grounds everything so all CG shots are quite a bit more work because you have to define what the shot is. Then you have to get the camera move to look real. And there were a handful of those CG shots in this. Our animation team did a fantastic job led by Simeon Duncombe, not only all the mandrill work, but just the camera and some basic photography needed to achieve this. Then we have to lay out a plan and do it one step at a time. I struggle every single project where I’m presented with, “here’s what the end goal needs to be, it needs to be higher to the mandrills on hundreds and hundreds of bridges, all moving, all reacting to each other and BCG environment chasing people on these bridge plates that are really messy and hard to deal with because they’re all stretches of ropes against the screen.” My first reaction is, how do I handle that. I remind myself that after so many years of doing this that, that’s good that you don’t know how you’re going to do it when you start; you just start laying out a plan and you just take it one step at a time and you just trust that every step is going to build on the previous step. And if you do it in the order that you planned it, then it will work and by the time you’re done, you won’t know how you got there. That’s what I love about the job, every project presents a new challenge that way.

Something I found interesting with the mandrills, versus the Apes films where they are really focused on developing the eye contact and light reflection within the eyes and the scleroderma around the eyes, here, you’re not paying as much attention to the eyes of the mandrills as the color of the face, because their color is beautiful and you have that captured beautifully. But then, the violence and the anger of fangs and teeth, actually look quite similar to some of the snarling with those hyenas that we briefly see within the film. So, I’m curious, how long the mandrill process took to develop their specific look before you start integrating and creating everybody else.

I think that the mandrills actually were one of the smoothest part of the process for us, in part due to just our vast experience in doing monkeys. Also, because they’re always moving and they’re always aggressive, it’s easier to do big action and aggression and animation than do anything in a bubble, like a drama. That’s where things like the eye contact, the eye darts, the very subtle facial expressions, they are really important. All the developments from the Apes films, we inherited. The way that I look at the techniques used to do on stuff, our animators are very experienced with. I will say that even given how action focused the sequence is, which means you can get away with a lot on the animation side when it comes to nuance, eyes still were repeatedly something that we had to go back and refine, refine and refine. There’s a handful of shots which are really focused on the faces for the mandrills and the comments usually coming were, “it looks great, eyes are bad.” The curse of doing CG animals or people or characters always will be, getting the eyes. That takes a lot of work and you still have to put nuance in there even at action sequences, if you really focus on the eyes. In many shots, we had lots of mandrills jumping over each other so you don’t focus on the eyes and you don’t have to do nuances quite so much.

But there are a couple of shots where the mandrills are coming right at the camera and it’s very effective. Tieing into that effectiveness is the fur on all of these creatures. Gorgeous job with the fur, Ken.

Thank you. The fur is probably the one area where our past experience on films during various types of primates really paid off. Obviously, we go from concept art and we start implementing it. It will end up being a bit of a back and forth with the client refining it. That was a very smooth process and it’s because we have so much experience with those types of furry creatures. We did the hyenas as well. The hyenas were a whole other story. Getting the fur right; that was a lot harder than it was on the mandrills.

They are scary. Those hyenas are ugly and scary.

It’s amazing you say that because a lot of the back and forth we had to try to get the fur right was, they look too fluffy and too dog-like so we had to keep on making them scarier, scarier, scarier and scarier. It was very lighting dependent. We had help with that too as we had just finished doing the new Lady and the Tramp with the CG dog. We have a lot of experience doing CG dogs. Dogs and hyenas, now you think they’re very similar but when it comes down to it, they’re actually very, very different in the way they move and the way they look. So, separating ourselves from jumping dogs was hard but it was the thing we had to do in order to get the hyena look working.

Immediately, because they were hyenas, I was thinking about what Favreau and his people did in the live-action Lion King with their virtual experience of what they created. I have to say, I think that your hyenas look much more realistic in their stance, in the bone structure of the stance, especially of the front legs. With the curvature of the spine and the head going down, it looked much more authentic and scary as hell.

That was the whole point. They had to be scary. But, I think with the anatomical proportions, early on we based our hyena off of a lot of data that was available for hyena from the, I think, from Los Angeles Zoo. I don’t think it’s San Diego zoo. And then we got the proportions right but as we learnt, it’s not just about the proportions, it’s about the posture. It’s very, very easy to make the hyena look like a dog if you set the posture in certain ways or incorrectly. One of the things we discovered, the curvature of the neck, keeping the head low, keeping their rear hunched and rounded over almost like with a dog – you think a dog was weight-bearing or was being scolded with the tails tucked under – but the hyena, that’s actually a point of progression. Going against your intuition and how you work with dogs was necessary. We had these anatomical features that have to be graduated through the animation to sell it and that was a learning curve for us. We got there in the end. I’m very proud of the hyena work but it wasn’t an easy as we thought it would be.

Well, I love the hyena work! As I said, that’s really what stood out for me, that spinal curvature with the head down and that nice, smooth downward curve. I didn’t see that with Lion King. So, I was really happy to see the accuracy and the authenticity that you brought to the animation of these hyenas. It makes up for giving the mandrills tails!

Thank you. At first when we saw the mandrills had tails in the concept we thought, “Oh no. They’re just going to be swinging from those tails”, which makes animation a lot harder. Then someone pointed out that baboon monkeys actually swing from tails and even the tails are most definitely not new with monkeys. So, we were able to get away with not having swinger tails.

Going back to the bridge sequence and the mandrills. With all of these bridges, you’ve got weight factors involved. As we always see with rope bridges, you’ve got planks breaking depending on weight, so you’ve got weight differentials to capture and create. As I said earlier, between Dwayne [Johnson], Kevin [Hart], and the mandrills, some of them actually look like they weigh more than Kevin, but you have such great balance happening. When I look at the bridges, you’ve got perfect sway and you’ve got the weight dropping some of those bridges down and it’s all continually shifting and changing. I’m curious how you went about executing that and specifically designing these bridges, which I know were built practically to an extent. But, I’m curious how you went about designing them and capturing those weight differentials and weighting the bridges themselves because they have to have some kind of substance to them as well to hold the weight that’s being put on them.

Actually, a real mandrill probably weighs as much as Dwayne does. That was actually probably the biggest challenge we had. We thought that with the chaos and within the action sequence, we’ll be able to just have the bridges just randomly undulate around and then we put the monkeys on them but we realized that work flow wouldn’t actually be really conducive to the way we want to work. Also, it didn’t work as well as having the bridges actually respond to the monkey animation. We had developed a pipeline where we’d have a bridge; our CG bridges were based purely off of the practical bridges on set. What we did is, we had the bridges to be rigid and we had the monkey animation going across the bridge, across the ropes, doing all that. And then, we would feed it to another group of people that use this quite specialized implementation of some commercial software called Euphoria that does physical simulations from animation. They take the monkey animation and would run it across the bridges and it makes the bridges move and makes the monkeys fall over the bridge as well. The monkeys would stick to the bridges and fall off the bridges, too, and that gets the dynamics. But then the result that comes out of that still has lots of clean up to do because you’d have monkey paws going through planks or crashing through ropes. So, then it has to go back to the other team that cleans it all up. Going through all those processes, it’s very time consuming, so our biggest fear was coming at the other end and having animations that they would have us to go back to the beginning and then go back to all departments. But the clients are very, very accommodating.

We laid out our plan early on how we were going to tackle the vast majority of animations, what we call vignettes because we realized from the trailer early on that with having a vignette and just changing the timings of the vignettes and multiplying it out through the frame and through the scenes, you can get away with a lot of repetition and not know that it’s repetitive. With the trailer, we had exactly one vignette. The vignette was mandrills on a bridge, running across and jumping up the other end. With that one vignette, we were able to do all the trailer shots with. So that was a proof of concept. We ended up having longer vignettes and more of them. We did just a handful of them. I think some of them were actually driven by actions that were needed in a specific shot, but they were still generic enough that if you saw the background of another shot, you wouldn’t think twice about it. We had to build a whole pipeline where these vignettes are treated as shots, where they go through this whole animation process I just described and on the other end comes the end result, including all the effects of debris falling off and dust being kicked up. All the dynamics on the fur or the secondary dynamics on the ropes that were added after all the dynamics of the interactions as all packaged up as the vignette, our animation team was then able to go back and place vignettes as animated elements. That meant that, in a lot of those shots, by the time we had the pipeline finally working, it was easier to add a whole group of bridges full of dozens of monkeys running across it than it was to change the animation on a single monkey. We tweeted that with Mark Gee [Visual Effects Sequence Supervisor] and they got on board. They wasted no time in saying, “Okay, get rid of this bridge over here. I want to bridge over here to two bridges with monkeys fumbling onto a third bridge.” They realized that they could actually pick the frame with a lot of monkeys on bridges rather than trying to hand animate individual monkeys. And that is the only way we’re able to get that done because if we had to hand animate every single monkey and every single shot, we never would’ve been able to finish it.

Wow! Just, wow! I love the suspension aspect of the bridges because they’re all essentially pulleys. They’re like V-pulley suspensions and I love seeing that detail even come into play with the bridge work.

Fortunately, the ropes of the bridges just disappear into the clouds and then you can’t see where they come from. The bridges they had on set were held by these steel things. A real rope bridge like would just collapse on itself. In our bridges, there’s still those invisible frames that hold the ends away from each other, but then it looks too rigid. It didn’t look right so we had to allow a little bit of wobble in it but still fitting constraints so that the bridges can’t just collapse and just fold up on itself. Everything that we added, the details are complicated quite a bit. But, we were happy. Unfortunately, anytime we’d show a bridge with dynamics of monkeys running across it, the first comment we almost always got was, you can’t make the bridges move enough. We build them frequently early on and just go bigger and stronger. Eventually, we finally did hit that point where we could make it big enough. We finally had one shot where we’ve done another thing – you’ve made the bridge look too much stuff on it.

How many bridges and monkeys did you ultimately end up with? Total in shots.

I think some of the shots we had 200 or 300 monkeys and on about maybe 100 to 200 bridges. It’s been a while so I’m guessing right now, but it’s definitely in the hundreds. And the bridges were more expensive to render than the monkeys.

And then you have to add people.

Yeah. The people. We had quite a few digi-double shots and some of them were digi-double takeovers where we actually have a live-action play of one of the cast members or a stunt double and you have to take them over within the shot into a CG version of himself and those are always the hardest ones to do. For instance, when Karen Gillan’s character, Ruby, is on houses picked up by the monkey and thrown, that top down shot of her being thrown from her halter top, it’s all from the photography and her waist downwards is all CG throughout the entire shot. That was lovely because she had a stunt harness that would’ve been very difficult to paint out and we found it easier just to replace her whole mid-section with CG. Also, it really improved the contact with the monkey that’s holding her by the waist.

You have all of these components but then you set them against this beautiful, beautiful gorge and the backdrop with the mist, the clouds, snow-covered mountains in the distance. If it weren’t for your nasty monkeys, it would look beautiful, almost utopic.

Thank you. There was perpetually a sunset there as well.

I have to commend you on the lighting because we’re getting 360° of light. We’re feeling where the sun is in the sky so that when everything is spinning, when the bridges are spinning and people are dropping and monkeys are dropping and then we’re going back up on a rope, we at least have a temporal context within the course of a day almost. How challenging is that lighting aspect of this?

When it came to the lighting and when it came to the layouts, one thing I should point out is, we had to guess early on how big the gorge should be before we had the whole sequence turned over to us. A bit of a handful of shots in the preview, we made a guess how big the gorge was and we laid out all the spires. I don’t know if you noticed that some of the spires have animals’ faces in them. Actually, there is a monkey spire, there’s a crocodile spire and in the background on a cliff face, is an elephant’s head. But, we had the whole thing laid out because as the sequence developed we realized that the gorge was not a big one and we were a little bit too far into the work we had done to go back and start over so we had to break the whole sequence stuff into bits. For each bit, when looking in this direction, we would shift that cliff face away and rearrange the spires and when looking in the other direction, we would do the same thing. We did that for everything. We had our base global layout which had to become stretched and treated. One of the things, and just for composition as well, when looking at a certain direction, it was boring so we’d say, “Well, we’re going to look a little bit more this way or we’re going to drop an extra spire right here just to give us a good composition and some depth layering in the background.” And lighting followed suit with all these bits. We had to make sure that the lighting was consistent with the storytelling aspect. The sunset is traveling South to North and the light of sunset in the West and the place topography was very, very good at maintaining light direction. There were a handful of places where our creative choices and with the edit method they used, shots were originally intended for different parts of the sequence, so we had to get very creative with the lighting so that we maintain that kind of storytelling continuity as well as matching what we did in the photography. But surprisingly, it only ended up being a handful of times we had to do that. I thought that Jumanji’s lighting was fantastic.

Did you have any specific reference that you looked to for developing the topography, the snow-covered mountains, and the foliage? Because, as you know, foliage can be so specific to a region so I’m curious if you had visual reference for that.

Yes. The whole gorge environment is based very much also, I’m not even going to attempt to pronounce the name, but it’s this Zhangjiajie National Forest in China. It’s the exact same location that was the reference for the Floating Mountains in Avatar. Since we were working with that film, the unique thing is that we just stole everything they’re doing but they haven’t gotten to that stage yet on the Avatar so we had to do it ourselves.

So now that they can steal from you?

Yes, they can! They probably are already. But the look of it based heavily off of that. T here was some beautiful concept art done by IOS concept division of what the gorge looks like, not only for the geography and the foliage, but also the mood of the sky, the clouds, and the lighting, so that drove most of what we did of trying to match that artwork. The balance between was good. We expected it to be this beautiful sunset but we didn’t know if it really was there. But there’s a beautiful sunset, there’s lighting on the gorge. It was just what we expected. So, it’s a balance between beauty lighting to make the foreground pieces look good and sunset lighting on the background. And that’s the perpetual struggle that we have with visual effects, you always want the foreground stuff to look good but you want the background stuff to look real. So it’s funny the trade-off, the transition and the balance between them.

It’s very funny that you mentioned that because in my notes as I was watching the film, I have little stars next to it, “foreground and background”, because I was very impressed with how good the foreground looks but also how beautiful the background looks as well and how realistic.

Thank you. That was, I’d say, a large portion of the assembly work that went into finishing the shot was the ability to balance the foreground and the background. It felt like an endless struggle trying to get those balances just right and I’m glad that you appreciate that.

Especially with this sequence that you guys did in the film, because this is the one that has the biggest delineation between your foreground and your background. Everything else is pretty much in a very contained space whereas, this sequence is not, it covers a much wider breath of air.

I think there’s a lot of those shots, especially the shots where the camera is right there with the characters in the foreground but there actually was a gorge exactly like this and this is all real. If they had a camera out there and they shot them for real, it wouldn’t look good because you’d have such a distinction between the foreground and the background, nothing connecting them. So, a lot of our work was actually not trying to make it look real, it was just trying to make it look interesting. Sometimes, real photography looks fake so we have to try to not make the audience jump out of the sequence because the whole purpose of the sequence is to get the eyes engaged in the action and the drama.

Ken, because I know that ILM did some VFX on Jumanji 2, as did MPC Rodeo FX, so I’m curious, do you work in tandem with any of those or is everybody independent and somehow it all looks cohesive at the end of the day?

There’s definitely some sharing of work. I heard that MPC did work on the film, as far as I know, and ILM did the concept arts so they were involved as art resource but they didn’t do any shot’s work. The vendors were primarily Sony, Weta, Rodeo, and the Method out of Melbourne. Rodeo and Method, we had to share some work still on the hyenas. We were the hyena vendor but sometimes behind the shop in a CG environment, we had to put our hyenas into another vendor’s CG environment. With the case of the mountain top fortress, Jurgen’s fortress, that was Method doing the fortress and in those shots, we did the hyena and we also did the CG crowds as well. Then the oasis environment was all done by Rodeo. There was a couple of shots where there was CG crowds and CG hyenas that we had to put into their environment. So, we did have to collaborate with them in the ground workflows for extension data.

For you, Ken, because you’ve been doing VFX for so long, you’ve been with Weta, you’ve been with ILM, you’ve been with Double Negative, which by the way, I have to say, I am one of the huge fans of John Carter, let’s just get that out there, I love that film and I so wanted to see sequels because there are so many books in the John Carter series. . .

Oh, you’re one of the five! Thank you! I want to see sequels largely because that was one of those wonderful experiences working on a project. Andrew Stanton was just a dream to work with. We were so proud of the work we did and it was such a good experience. It popped on TV here and I hadn’t seen it in years. I was really pleasantly surprised at how well the visual effects held up all this time.

But, I’m curious, now that you’ve gone through this process tackling new things with the rotoscoping for the rope bridges and the building, rebuilding, cut and paste so to speak for the layperson, what did you take away from this particular project or what new technology that you came about that you’re going to be able to use in your next project?.

Well, I don’t know our next project but the workflow and technology that I’m most excited about to solve problems on other projects that we may be working on and potential future ones that I don’t know that yet I may work on was the vignette workflow for getting the large amounts of coupled animation between environment pieces and characters up to a really large scale. The workloads that were created for that, I think, works phenomenally well. I look forward to having an opportunity to do something like that again. There are small bits of technology that we’re quite proud of. One of them is rotoscoping of the ropes on the optical bridges. The ropes are so thin and when they’re moving, the motion below it, there’s no way you could rotoscope down. First off, you would spend a fortune rotoscoping them and then the rotoscope wouldn’t be useful for extracting the actual works of the place because through the motion blur they were so mixed with the stuff in the background and it’s really difficult, the way things are moving, for us to get really good blue screen coverage back there. So, you would end up using the rotoscope just to reconstruct something that looks like the rope but you wouldn’t have the ways to add texture or shaving or anything like that to it. Our component’s supervisor, Robin Hollander, came up with this technique for using open lines so our rotoscoping artists can have the option, usually they close those lines and they make a whole loop around something, but to keep it open, it’s not a common workflow, but you did indeed get the way of actually adding texture to it and you can also keep it a lot simpler. There’s this whole workflow technique where our rotoscope artists could very intuitively do a really rough blocked out outline of the ropes and then add detail just where they need to and then those lines they would draw would actually get textured to make quick ropes. We would just also replace the ropes on the bridges where they became problematic or they’re going over the actors. That was a system called a Ropo. It wasn’t used a tremendous amount, but where it was used, it was essential. It’s just really clever and we’re quite proud of it.

by debbie elias, exclusive interview 03/26/2020