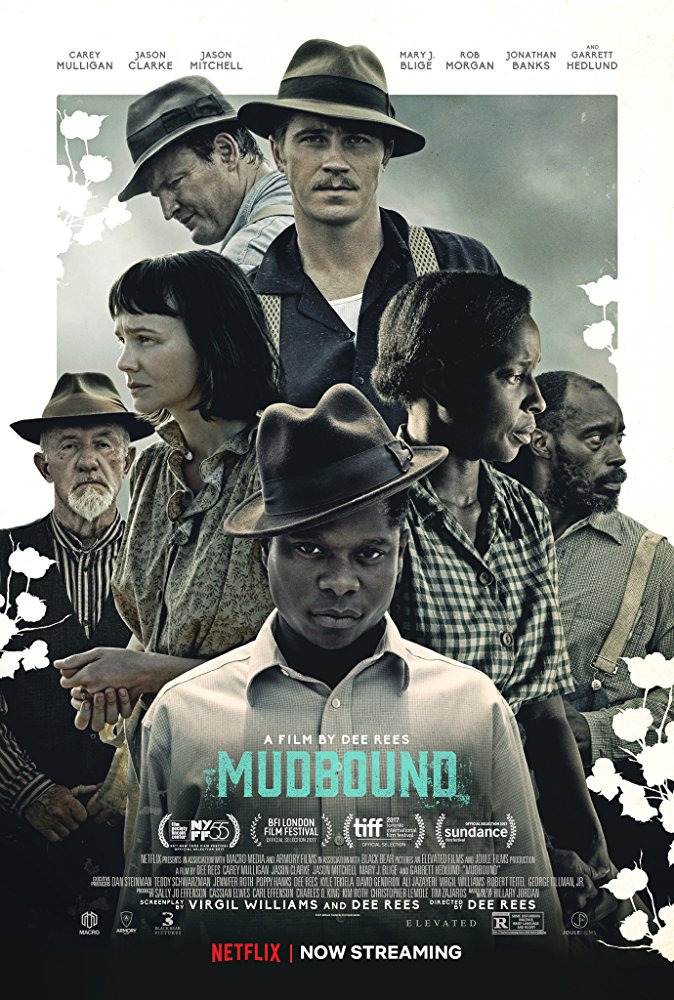

Cinematographer RACHEL MORRISON has been a visual voice in the cinematic spectrum of independent filmmaking for almost two decades. In that time, she has added texture to the storytelling of directors like Zal Batmanglij, Brad Leong, Tim Heidecker and Eric Wareheim, Daniel Barnz, Sara Colangelo, and most notably, Ryan Coogler with “Fruitvale Station.” She has a keen visual eye and understanding of story elements, making her a gifted asset as a cinematographer, and she knows how to appropriately and judiciously use all the tools in the filmmaking toolbox. Working with director Dee Rees on her latest film, MUDBOUND, Morrison was required to flex all of her cinematographic muscles as she helped bring the tapestried and textured beauty and brutality of a post-World War II southern United States to life through light and lens.

Tackling the muddied browns and greens of Mother Nature, the ethereal purity of an aviator’s horizon, the golden candlelit warmth of an overcrowded wood shanty, the softness of the moon, the darkness of ominous rain-heavy clouds, and most importantly, the life found on an individual’s face or in the dirt under their fingernails, RACHEL MORRISON delivers award-worthy work with her most beauteous and metaphoric work to date. So strong is her work with MUDBOUND that no one should be surprised if the name “Rachel Morrison” is announced as a nominee for an Academy Award for Best Cinematography come nominations morning.

During this exclusive interview with RACHEL MORRISON, we talked about not only the visual construct of MUDBOUND and the considerations of film versus digital lensing, but working within the confines imposed by Mother Nature. . .

I have so admired your work for so many years. What you did with Zal Batmanglij and Brit Marling on “Sound of My Voice”, I thought was really exquisite. And “Little Accidents.” I think it is one of the most beautiful and emotionally haunting films.

Oh, thank you. That means so much to me. I’m so glad you’ve seen “Little Accidents” because that was one of those ones that I feel like sort of fell through the cracks.

It did, as did “Cake” to a large degree, but not as much as “Little Accidents.” You even did “Tim and Eric’s Billion Dollar Movie.” But then your pair with Ryan [Coogler] on “Fruitvale Station” – and now I can’t wait to see what you’ve done with him on “Black Panther”! These films really show this great progression for you as a cinematographer in storytelling. You have such a diversity of what you can do with lensing. But with MUDBOUND, this all comes together and I’ve got to tell you, you got one hell of a workout on this film.

Oh, thanks! Yeah, that much I did.

Your lighting and lensing is as much of the storytelling here as the script itself. It is exquisite, and I will not be the least bit surprised if I hear your name announced come Oscar nominations morning with a nomination.

Wow. Thank you. And even to get to the point that anybody would say that is very exciting for me.

How do you approach a film like MUDBOUND? This is very much about man’s relationship with the earth, more so than man’s relationship with man. As we see so eloquently in your visuals, we have a middle class, upper middle class family, with money, who buys a farm. They’re living in a shanty. Then we have a black family working the farm. They’re also living in a shanty. But when push comes to shove, they’re essentially the same, and everything in life falls to their respective relationships with the land. So how do you approach that from a visual standpoint before you even get into thunderstorms and rain and mud and everything else?

I think that the big challenge was how do you photograph the American dream contrasted with the American reality? It’s the land is idealized versus land as not unkind, but untameable. So, we started by deciding we wanted to be widescreen because that sort of seemed like the obvious choice to be able to look at isolation and how small man is when compared to the land around them. And then it was just talking about how do you find that balance between just enough beauty to denote hope and to show how somebody can dream of something more, and then contrast it with grit and dirt and the reality of things aren’t always what you hope them to be.

Before you can shoot anything, particularly with a film like this, you had to be very specific with your camera and lenses in order to achieve the visual texture that we see in lighting and in the tactile tangibility of the film. What lenses and camera did you land on that would give you the range that you needed to capture everything that you eventually went on to capture here?

You’re exactly right. “Tactile” was probably the number one word in my head because I wanted the audience to be able to sort of feel the mud. You’re trying to make something three dimensional that’s perceived in two dimensions. So my natural instinct was to shoot on film and I think Dees’ as well. Even the period is so rife for analog. When I think of the 1940’s and in the south, it feels more like the ’30s because things haven’t progressed quite as fast as they have in urban places, I just immediately go to the light photography. It’s so incredibly analog. So out of the gate was this “Well, we have to shoot on film” but the reality is, the budget set in and it came down to shooting days or celluloid, and we barely had enough shooting days to tell the story we were trying to tell in the first place.

I wanted the grit to be visceral and the elements to be visceral, and to feel like the audience was experiencing the weather and the mud the way that one would hope somebody could taste food in a scene or something. For me, it started with wanting it to be analog, and then we really wanted to have a visible grain. And we did a lot of testing. 16mm, the grain was perfect, but the resolution sort of broke down in the landscapes. I think it was sort of perfect for “Fruitvale” because it was all so small and intimate. But with this, we wanted to contrast these intimate scenes with obviously these much much bigger, kind of epic scenes that had a lot of scope to them, and unfortunately, the 16 didn’t quite hold up for the wide landscape material.

Then with 35mm, it would have been perfect except ultimately it just came down to a budgetary thing, and we were given a choice between shooting on film and losing two days of shooting time. And this was so ambitious already for the budget and the schedule that we had that losing two days just was impossible. So then it was all about how to make analog feel. How to make digital feel like analog and really, I wanted a perceivable grain, so we ended up adding some in-camera by rating the camera at a higher ISO than I normally would, and then adding more in post.

Then it’s just obviously the texture of the lighting and the contrast. And it wasn’t beauty lighting. It was all about you want to just feel, read dirt on people’s faces. And there was no beauty makeup. A lot of the characters had no makeup, even to the point in the first few days I kept saying, “Hey, they’re getting super shiny” because it was a million degrees in the summer in the south, and I thought for sure we would powder down some of the shine. And Dee [Rees] said, “No. If this is what it feels like, we should read it. People should be sweating all the time.” So we leaned into that.

I loved seeing the sweat because that is exactly how you feel down there. I’ve spent time down in Omaha, Georgia, right on the Chattahoochee River and the Hannahatchee Creek, and it is a humidity bloodbath. You’re dripping and you are glistening all the time, and even if you’re not outside in the dirt, there’s dirt in the air so it sits on your skin. I loved seeing that in this film on everybody. And of course, when you talk about no beauty makeup, remember you’re lensing Garrett Hedlund, for God’s sakes. He’s going to look gorgeous no matter what you do.

Yeah, that is true.

I do have to say I’ve never seen anyone capture Garrett’s eyes as beautifully as you did. Those eyes of his are so expressive and they’re so vibrant, and that really fits the character Jamie McAllan whom he plays, with the frustration of life. I think it is the most beautiful and authentic, lensing of Garrett that I’ve seen.

Wow, thank you.

What lenses did you end up using? I’m guessing you went with anamorphics.

We did for most of it, but I actually ended up mixing anamorphic with spherical, which I had done for the first time on “Confirmation” but for a very different effect. I could go into why I did it on “Confirmation” but in this case, the reason I wanted spherical in it as well, initially it was because I wanted the fall off and the bulk of anamorphic that felt to me very, there’s an old quality to it. There’s a softening, a natural softening around the edges of the frame that reminds me of old photography.

But then, I wasn’t interested in the horizontal flairs that are so often associated with anamorphic glass, and that kind of J.J. Abrams flair feels so contemporary to me. So I initially got a set of spherical lenses for the express purpose of when I was pointing at bright forces like the sun, to replace, to shoot, that spherically just so that we would have that kind of round, analog feeling flair.

I realized that for a lot of the night work with some limitations of lighting – even if we had the biggest lighting budget in the world – I wanted to do so much of the lighting with candlelight because that was essentially in the Jackson household where they have no electricity. That was the source. In order to do that, I needed to stop from the faster lenses. So I got old spherical lenses as well; a sort of mixture of ‘ 60s and ’70s Ultra Speeds and Super Speeds. I really just had a battery of old glass. I don’t think anything was newer than the late ’70s. And I would say probably in the end, it was maybe 70 percent anamorphic, 30 percent spherical, maybe 60-40, somewhere in there.

It came out beautifully, and I’m glad you mentioned the candlelight. It’s so beautiful and what it does in the Jackson home, it really sets up the contrast that we have these two families, they are both living in essentially these shanties, these wood shanties with cracks in the walls. And even though one may have electricity, it’s not working. So they’ve got candlelight but not to the degree with the warmth and golden glow that you give the Jackson house. This is where the visual really takes hold in the story because we feel how much wealthier and how much richer the Jacksons really are over the McAllans, and it’s because of that golden glow and the warmth. The reflection of the wood is beautiful in the Jackson home, whereas in the McAllan home we get such small reflection because there might be just one candle lit instead of multiples lit. And it’s just lighting one tiny, little area so the rest of it, much like their own family and relationship dynamic, is in the dark. Stunning work, Rachael. Stunning.

Oh, thank you. You’re definitely astute to pick up on all that because that was certainly the intention. And even just the tones of the Jackson household where there was so much more exposed wood and then that sort of warm newspaper tones. Whereas the McAllans, there was more color in it but you didn’t feel any of that because it was just all faded and the lighting was so much colder and everything else.

And I love the way that you captured the paint peeling off the wood in the McAllan house. We can see the paint actually peeling, the chips that are hanging. And that detail that the camera picked up added so much.

Yeah, thank you. A lot of that I would love to extend the credit to our fantastic production designer, David Bomba. I think the layering and the texturing was really one of the things he did so well. And then for me, it was just how to not screw it up.

You were, however, essentially at the mercy of the elements, so how challenging or what kind of challenges did that present for you? You’re shooting primarily with natural light, especially in the daytime and your nighttime exteriors. So how did that impact your planning and your shooting? Because I know the sun bears down, it’s hard, it’s hot, it glares.

It was rough, honestly. I’ve never had anything quite like that in terms of shooting. The elements were obviously a motif in the film, and we lived it. The idea that as much as you think you have the tools to kind of conquer the land or you could be prepared for any weather situation, the reality is the weather will always have you beat. For us, the hope is certainly that everything looks like it was natural light. The reality is that the interiors were very, very lit. It’s just to be able to kind of maintain exposure with what was happening outside we had to put a lot of light into the room.

But as you mentioned, outside – and there are a lot of exterior scenes – we’re very much at the subject, at the mercy of the weather, and it is tough in the south. You’d be hard-pressed to get three hours of consistent weather. We’d start a scene in the sun; within 45 minutes it would be pouring rain, and then 20 minutes later the rain will have cleared up, and now everything’s wet but it’s dry. And then you have patchy clouds. We don’t have that in L.A. In L.A., it’s either a sunny day or on rare occasions it’s sort of overcast all day, but it’s continuous. The idea of bright sun followed by thick clouds followed by bright sun becomes just such a challenge for continuity, and that was something that I was, I wouldn’t say ill-prepared for because there’s really at the end of the day, there’s really nothing can do about it. You can plan for the worst but like you said, there’s just no getting around it. You can’t break up scenes and keep going back and forth between three different scenes based on what the weather is, so you just end up oftentimes trying to wait for a patch of clouds to dissipate long enough to get a patch of sun and be ready to roll in those moments.

Then, for the first time in my life, I had a reverse cover set plan. Normally if it rains you go inside. But we had that one scene of digging out the grave for Pappy that we needed a certain amount of real rain for, for all the wide shots. So I had this crazy idea that anytime we knew we were getting rain, we would go get the wide shots for that scene, which to some extent worked. But even then, it’s like just when you’re set up and ready to roll, it’ll rain for two minutes and then the rain will subside and it’ll be a beautiful, sunny day and you have to go back to something else. The weather kicked our asses, but in some ways I think it certainly was helpful for the actors when you really start to live that. Laura [Carey Mulligan] says that she dreamt in mud, she dreamt in mud and she never felt clean. I think we were all in the same boat with her.

But then I’ve got to ask you the all-important question. I’m guessing you were shooting on sticks or trying to do dolly or tracking, so what does the mud do for you then in that situation?

It was tough. There was a ton of times, but two things about it were especially tough. One, is that Dee had really wanted to be able to shoot 360. We’re out on a plantation with no cover anywhere so not only is there no protection from the sun and the heat, but also there’s no real place to hide your gear. So then we would try to give ourselves this sort of pie slice where we would put all our gear so we could at least shoot 270, 270 degrees. And then when it was time to change pie slices and move all the gear 180 degrees from where it had been, it was all stuck in the mud. We literally had times where we’d need to bring in bigger vehicles just to pull our condors out of the mud or whatever it was. And as far as dolly, we did a lot of handheld actually out of, somewhat out of design, but also at times out of necessity because it’s true, it just would have slowed us down to be constantly trying to lay dolly track in the mud. We definitely did a lot of dolly shots, too. I think everything sort of starts on half apple boxes and those apple boxes are completely caked in mud for the entire duration of the show but just to get you above ground level. Then we also did a lot of crane work for that reason. Because at least with a crane, once you get the base where it needs to be you can kind of extend it out. I say ‘a lot’ but we were on such a limited budget it was more like whatever we could afford.

Something that working in the elements gave you that I think a lot of cinematographers and directors may not appreciate is, because of that fluctuation in the weather every day, it gives you those beautiful, beautiful ‘magic hour’ shots and some real money shots in the film. You’ve got some stuff there that you just pull out and they are a money shot ready to hang on a wall somewhere. They are so beautiful, some with the clouds rolling in, others with the sun over the fields. I mean, beautiful.

Well, thank you. The interesting thing about this film is in wanting it to feel, in wanting to contrast the ideal with the reality. Even if we had had all the time in the world to be Terrence Malick, that wasn’t quite the right look. So for all the quote-unquote “money shots” in the film, if you knew how many times we were eating lunch during the most beautiful sunset I’ve ever seen! The DP in me was dying a small death watching how magical this all was. But the reality is it just wasn’t right for our film to be beautiful all the time. So that was also a first – just literally like taking lunch during magic hours sometimes because on that day we wanted harsh midday sun.

But I have to say, the shots you have – and I think not “going Malick” on the film, but having judicially placed just a few shots – really makes you appreciate the beauty of life set against the isolation and hardship of man against the earth.

Yeah, yeah. Thank you, and that was definitely the intent.

But you do also got to get out of the mud. You get to the pre-marriage scenes and the early marriage scenes of the McAllans which are beautiful and very period-perfect. Then you get action sequences in the war, aviation, and then the exquisite white-on-white purity that is metaphoric on multiple levels in Germany, which we know is a set. So you got to play with all of that as well. How did you approach those visual aspects of the film?

The starting point was just how do we make that feel different from life on the farm. Let’s say, the pre-farm scenes. In every case it’s how do we make each of these scenes feel different from life on the farm. And in the case of Laura’s pre-farm life, it was obviously more colorful, more saturated colors, richer, more velvety fabrics obviously in her costume design as well as the production design. I wanted a more neutral moonlight, which is what I associate with a city. In most of my films I always have treated moonlight as white. But with the farm, this is the first time I went into this sort of more wild kind of turquoise-y green-blue. I felt like there’s something about what moonlight is, it’s its own source and there’s nothing else but candlelight to kind of compete with it and nothing feels white.

For the war scenes, I wanted you to know immediately that you weren’t at the farm, but I also didn’t want it to feel too sort of flashback-y. And then I think there’s a tendency to, whether it’s [inaudible 00:24:35] shuttering or going with a crazy, intense sort of green-blue color palette or whatever it is, I wanted it all to fill the hole. I think that was sort of the challenge, too. We sort of have all of these different storylines, all of these different family arcs, and you want to show their differences, but you still want the piece as a whole to read kind of fluidly, especially when you do have things bouncing around at times. So it was trying to find that delicate balance where you know you’re in a different time and place, but it still feels cohesive to the whole film.

What I found striking is that the pre-farm days, we see Carey’s character Laura and we see her family life pre-marriage to Henry McAllan [Jason Clarke] very much akin to what we see with the Jacksons. I love that differential and that contrast that we see which explains why Laura gravitates towards the Jacksons at a certain point in the film. It represents what she had. But there again, we’ve got the ‘haves’, they’ve got money and they’re well-to-do but they’re still a close family. And then we have a family that has nothing but love for each other that is warm and wonderful. And I love seeing that in those two settings from you. But then I also particularly love the white-on-white that you did in Germany. Beyond striking.

I again kind of deferred it to David [Bomba] a little bit because that was a location shoot. We actually shot those scenes in Budapest and he went ahead to scout. He basically found the locations and sort of determined that they would work best and this is why. And of course, as a DP, I think my initial instinct is, “Are you sure about this white-on-white on white thing?” I think he had real vision in mind for it so I just did my best to support that vision. I agree that it worked really well. I just took inspiration from what I was given which was a white room and kind of decided not to muddy with colored light. But it was really, I think, his brainchild.

Then you also get that similar tie-in of the war with Garrett’s character of Jamie up in the clouds, which is also white but you’ve got texture, which I’m sure that’s CGI. But still, you’re shooting this so you’ve got to light for that so CGI can balance and match it. Another beautiful, metaphoric tie-in that’s almost as if the purity of the war was better for these two men [Jamie McAllan and Ronsel Jackson] than being back on a farm.

Yeah, and certainly cleaner in its own way. I hadn’t thought about that but maybe that’s what the white, the juxtaposition is. I don’t think anything else in the film probably at all was white. The rest of their world is caked in mud.

There was nothing else that was white and that’s what really hit me when we would see that. Plus, it speaks to the whole underlying tones of a black man with a white woman. There’s so many layers at play, but it’s the visuals in this film that really bring it all to light. I don’t know how many people are going to see that, but they sure need to.

Hopefully, you can spread the good word. My hope is that enough people can see it in the theater. I’m thrilled, obviously, that Netflix bought it and they’ll up the mass release for it because they did sort of a nice playing field where most people at this point can get Netflix in their homes. But I also, there is a scope to the film that wants to be on a big screen. Also, I think it’s almost less about the size of the screen and more about what happens when you go into a dark room for two and a half hours and there are no distractions, and you’re not looking at your phone or getting up to go- well, maybe you’re getting up to go to the bathroom, but you’re not taking these little breaks because I think you can so easily be pulled out of the experiential element of a film when you watch it in your own home. I’m as guilty of it as anybody, but my hope is that there’s enough of a push to see it in the theater during its limited release or whatever.

This film has to be seen on the big screen to really appreciate the beauty of everything that is in there, particularly when it comes to Jason Clarke’s character of Henry. Although the character Henry is really despicable to a large degree, you understand him. Clarke’s performance is great, but it’s so much due to your framing and the idea of subjective naturalism and isolation that it just enhanced his performance to a such a degree that he commands the screen. Having seen Clarke in “Chappaquiddick” the morning before seeing MUDBOUND at night, I have to say that his performance here was totally elevated because of the cinematography.

Well, thank you. That’s certainly my hope, and that’s the goal is to always sort of support and elevate the performance by helping to mirror the emotional states with the lighting and with the compositions. I’m happy to hear that you think I succeeded.

Before I let you go, Rachel, I’ve got to ask you this. As a filmmaker, a cinematographer, you always take something away from every job that you do, every film that you make. What did you personally take away from the experience of making MUDBOUND that you’ll now take with you into future projects?

I think honestly, and we talked about this, but I think we all got our asses handed to us by Mother Nature. I don’t know if it’s that I’ve shot so many other films in more interiors or in tamer locations or whatever it is, but I think that was a real wake up call on how to better prepare one’s self for the elements. That was the biggest, I think, learning curve for me on this film. I guess it’s possible that there are even greater elemental challenges. You read about how hard it was on “The Revenant” and things like that. But when the script title is MUDBOUND you should have some sense of what’s coming, and yet I think we still were all a little bit blindsided by just how inconsistent and yet overpowering the elements were. So I think that now my tools will change as a result of that lesson.

Of course, now that you’re shooting a tentpole like “Black Panther,” a Marvel extravaganza, how does it compare to all of these smaller films that you’ve been doing?

I guess you bring all of the things you’ve learned on all the small films and then you put it in a giant arena. There’s certainly been a ton of new lessons on “Black Panther” because I’ve never done as much with the visual effects as I have on this film. So I got a really great education in how that world works. But at the end of the day, I think these movies – even the big ones – are made or broken in the intimate moments and the performances. Hopefully, everything I’ve learned about how to support a character’s performance with lighting, that will still shine through in that superhero context. That’s my goal.

by debbie elias, exclusive interview 10/21/2017