Jean Seberg. An American actress immortalized thanks to French New Wave cinema and her iconic and unforgettable performance in Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless, Seberg’s career began with her tragedy-filled film debut in Otto Preminger’s Saint Joan where she sustained severe burns as the result of the burning at the stake scene gone wrong. Literally and figurately burned at the stake with the release of the film, Seberg was undeterred in her pursuit of an acting career and followed up Saint Joan with Bonjour Tristesse and The Mouse That Roared before striking gold with Breathless.

Constantly crossing borders between France and America, French New Wave and traditional American cinema, motherhood and marriage, emotional stability and instability, Seberg proved to be a complex and complicated individual. An actor, an activist, an icon, a woman, thanks to her association with the Black Panthers in 1969, Seberg landed on the radar of the FBI and became the main target of J. Edgar Hoover through the COINTELPRO Project; so much a target, in fact, that FBI records have shown that Hoover kept then-President Nixon informed of Seberg’s activities and the FBI investigation of her. Long a supporter of various civil rights groups, thanks to her acting profile, Seberg became the face of the FBI investigation and resulted in their abuse of her civil rights by defaming, harassing, stalking, intimidating, and surveilling her, as well as wire-tapping and surreptitious break-ins into her Hollywood home. The FBI even went so far as to create and plant false stories in the press about Seberg. This was indeed a time of “fake news.” The emotional strain proved to be too much for her, yet it perpetuated for years, forcing her back to Paris and effectively blacklisting her in the film industry. In 1979, her decomposed body was found in her car.

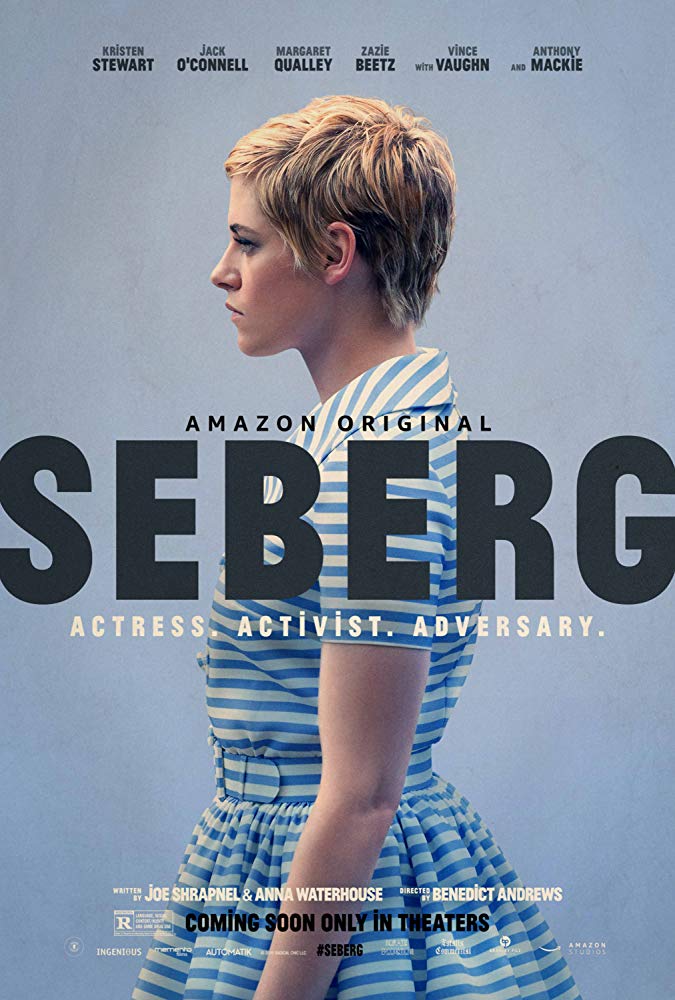

With script by Joe Shrapnel and Anna Waterhouse, and starring Kristen Stewart as Jean Seberg, director BENEDICT ANDREWS examines and brings to life the tumultuous period in Seberg’s life where she was under the invasive and intrusive microscope of the FBI and all that constituted their investigatory pursuit of her. Immersing us in the period through costume, cars, color, architecture, and lensing, we are transported in time and place in an almost voyeuristic sense as we see and experience this chapter of Seberg’s life through the emotions of Seberg and the gaze of the FBI agent heading the investigation. Co-starring Anthony Mackie as Black Panther member Hakim Jamal, Zazie Beetz as Dorothy Jamal, and Vince Vaughn and Jack O’Connell as FBI agents Kowalski and Solomon, respectively, under Andrews’ directorial eye, performances are rich and emotionally telling, with none moreso than that of Stewart and O’Connell.

I spoke at length with BENEDICT ANDREWS discussing his approach to SEBERG and particularly the very metaphoric visual design, starting with two captivating opening sequences lensed by cinematographer Rachel Morrison which set the tone of the film. . .

I must congratulate you on such a rich, lush, gorgeous film, Benedict. I was spellbound watching SEBERG, due in large part to your visual tonal bandwidth, your visual construct, and snagging Rachel [Morrison] as your cinematographer. The entire visual and structural design of this film is so well done.

Thank you very much.

It is a visual stunner. I’m very curious as to how you planned the design of this film, especially the visual design. From Rachel’s [Morrison] cinematography, which is bright, to your color saturation which is spectacular. But then you get into night scenes, and by the one hour mark of the film, it’s definitely taken a much darker noirish turn and we get inkiness, nighttime inkiness, thrown in there. And all of this starts with one of the first opening images that we see of Jean standing there, looking in a triptych mirror, almost as if telling us we’re going to see the actress, the activist, and the woman. So I’m very interested in how you approached this. What was your thought process for the design and construct of this film?

The kind of crystal [ball] of that mirror was also a very prolific beginning for me and that the film, as you’ve mentioned, is about those different facets of her. But it’s also a study of identity, and the identity of an actress, and the private space of an actress; and as somebody who’s been lucky enough to spend most of my life working in the theater with great actors and actresses, to be so aware of how they put themselves on the line and how they need to mine their own private space, their own memories and emotions, and raw nerves, and all the things that we usually keep hidden. The actor has to expose those facets of themselves in front of the camera or on the stage, and this is exactly the same place that the FBI’s surveillance cameras go into and destroy, it seems. So starting at the mirror was also sort of a bit like almost a backstage shot of seeing an actor in the dressing room mirror before the venture up to the stage, and before she ventures off into the world.

That really sets the tone. Of course, this is after we see the recreation of Saint Joan, which as anybody who knows anything about Seberg knows, the film’s director, [Otto]Preminger was obsessed with authenticity. And in filming Joan of Arc being burned at the stake, something went wrong, Seberg was burned, the flames were real. That also speaks to Seberg and her activism, play with fire and you’re going to get burned. So to open the film with that image, that also sets us up for a beautiful entré for what is to come in terms of she is playing with fire, hanging out with the Black Panthers, and she is going to get burned.

Interestingly, in that prelude as well, what I wanted to focus on with this theme with Preminger was that we’ll come back to it several times over the movie as a kind of red thread, or a clue. We’ll see it again; the actual real documentary footage of the on-set accident when the FBI character Jack is doing his research into. But in this first moment of the movie, it plays like a kind of dream or a nightmare, and a kind of prelude. What also interested me is the way that the camera is pushing in on Jean. Then we see her seeing herself reflected in the matte box of the camera as it floats in towards her. This was also sort of setting up for me where the action of the movie was going to be. Here’s this woman who’s living her life in front of cameras, both … so the hidden ones of the FBI, and then the ones of the movie she’s making. And this sense that here was someone who was also trapped in that gaze, and whose identity was about performing in front of the camera, and who was looking for something else, and looking for a way out, and looking for a kind of truth.

Of course, with the whole concept of being trapped under the gaze of the camera, you beautifully follow that through with your production design, and the Seberg house in Los Angeles, all glass. With all glass, the beautiful framing, the steel framing that portions out that very long glass hallway so that she is always under somebody’s gaze, but in a very confined manner.

It’s a beautiful house and was a very deliberate decision of ours, working with production designer Jahmin Assa and with Rachel, to say this film is so much a study of somebody who lives their life in public and lives in a kind of glass house. In the beginning, it’s like you feel her loneliness in that house; she’s throwing ice cubes into the swimming pool, and the camera is watching her drift through those empty rooms. And later on in the movie, that house will be filled with people when she has the party for the activists there. The spaces are important. To come back to your first reflection about the production design, it was important for all of us that the spaces in the movie became kind of characters, that they had absolute period authenticity and broke through clichés of the period, but that each of them also became characters in their own rights. The movie is about someone who is a kind of border crosser. In the first minutes of the movie, she moves from beyond what those prologues we’ve been talking about represent and also moves from her place where she lives with Romain Gary on the Left Bank in Paris where they’re the darlings of the French New Wave, and she flies to Los Angeles and comes to that beautiful glass house in the hills, and drives her car down to Hakim Jamal’s house in Compton, followed by the FBI. So in those first 10 minutes, we’ve crossed all of these different worlds. It interested me how she was a boundary crosser and she kind of dragged the movie through these different places with the FBI follow her through these different worlds. So each of the worlds wanted to have its own character.

And you define that so well with color. As you mentioned, it’s period-perfect with the cars, with the costuming. Michael Wilkinson’s costumes are fabulous. And your color selections, putting her in a lot of yellow. Caution. And in the third act, that rich emerald green, more or less metaphorically saying, “Go. Go on with life,” after that meeting with Jack in Paris. What were your considerations for the color and the saturation because you keep us in this heightened state, almost a slightly surreal element, that this is really happening to somebody. Is the FBI really pulling out all the stops to do this to somebody? Is she really as committed as she appears to be? It’s all very interesting and it plays into your color choices and the heightened saturation of it. So I’m curious as to your thoughts on that.

That’s interesting you touched on that sense of what is true and what is not true. She described this period of her life, looking back on it as a kind of long nightmare where she no longer knew, she says she possibly never would know, what was true and what was not true. And the movie depicts this kind of sense of the walls closing in on her, and also her sense of truth and her sense of reality being destroyed. As an audience, we get to see both sides of it, where Jack is a kind of voyeur, looking into her life and kind of pulls into the kick of that voyeurism, and the danger of that voyeurism, and the ethical choice that leaves him. And then we’re on the other side of it, going under with her. I was interested that while absolutely believing that she was completely committed in her cause and fighting to make real change, she’s also someone who is living between realities. One of the big scenes with her and Hakim Jamal, the scene is effectively an audition scene for Paint Your Wagon. She’s slipping between all these different roles that she’s playing. She’s kind of flying blindly in the first half of the movie and has that ground kind of pulled out from under her and the film does start to play into that kind of nightmare. I wanted on the one hand for there to be a real deep photographic beauty which led to the decision by Rachel [Morrison] and I to shoot on film and to use the same Panasonic C Series lenses that those great surveillance thrillers of the ’70s were shot on, with that kind of nod towards those surveillance thrillers. I love how those movies are simultaneously tense and mysterious, and the identity of the individual in crisis is also kind of taking the temperature of the society that is in very real crisis.

At the 50-55 minute mark the film’s tonal bandwidth shifts to a great noirish feel, deeply ensconced in the surveillance that’s happening. Seberg is out on a balcony in a hotel at night which, I have to tell you Benedict, is one of the most beautiful shots in the film; that blue-black inkiness with just peppered lights from other buildings. Absolutely gorgeous. And based on what you’ve created up to that point, you wonder who’s staring out of those windows, maybe seeing her as well. But I love how you take on a noirish tone by that point. Was that by design? Was that happenstance? Serendipity?

I think the kind of dance of filmmaking is always a combination of those two things. My team and I planned rigorously and looked for a whole series of period references and discussion of the different evocative qualities of each space. And then we were also making an incredibly ambitious period movie on a fairly tight budget, a movie that wanted to have all of that, to aspire to all of the elegance that you’re describing. For instance, in that balcony scene, we shot Paris in New York and LA. I had quite a few restrictions in that we’re looking out a window in Downtown LA and kind of making that speak for ’60s midtown New York. I think in filmmaking it’s where the life of the movie ultimately comes from. Even when you’re making a carefully constructed period movie, it’s a dance of accidents and contingencies, and I think that’s where a lot of the kind of beautiful life of the movie comes from. But even when we’re in that fantastic final scene, that amazing green shirt that you described, it also has a lot of emotion in it, and also speaks to me as a kind of shifted era. Now it’s starting to lean into the ’70s more, and not just in terms of period, but in terms of Jean’s life in the ’70s; her on kind of the other side of this wave that’s crashed over her life. That scene was originally meant to be in a bar on the Left Bank, and we used the bar of the Biltmore for Paris. But it gets another evocative quality, that as the audience is sitting there, I think they’re pulled deeply into the cinema and the dream of Jean’s life. So yeah, I think this is where things come alive on the screen; where there’s this balance between the construction and discovery, or else things start to feel too formal. I think this is something that I’ve always looked for in my work in the theater, that I’m proud of in this movie too, is this tension between a kind of formal beauty and a kind of raw and impulsive inner life so that you feel the things pulling at each other, and the friction of these two things. A lot of that also rests on the aliveness of the performances and on Rachel’s camera. So in terms of you’re talking about, there’s a shift. The audience gets pulled deeper under in the movie, and deeper into the kind of nightmare. Rachel and I also had the question of how do we portray the walls closing in on someone, and how do we make manifest in the camera her descent into paranoia. The first half of the movie things tend to be more on sticks or on Steadicam, and gradually the camera becomes more handheld in the second half of the movie. And with Rachel, not only do things have that kind of beautiful painterly lighting that you’ve described, she’s an extremely sensitive handheld shooter. You see that going back to Fruitvale Station. I was excited to see what would happen with that dance between her and the actors once the camera started to come off sticks like that.

It’s absolutely exquisite the way she captures Kristen [Stewart], in particular, in her performance. There is so much silence. And Kristen’s face in moments of silence, you can almost see the wheels turning in her head, and you very smartly and judiciously let the camera just rest on that, in a slightly skewed closeup. It’s perfectly framed, but it’s slightly skewed, via either profile or just offside face frontal. It tells us so much. It speaks volumes, just those quiet single images like that, and it’s just beautiful to see.

I think it speaks to a real trust between Kristen, Rachel, and myself, and that we’re all chasing down that same living kernel of the movie. Those closeups – I was playing with them a lot in my first movie Una as well, and I think they come out of someone who works between theater and film. Now, Ingmar Bergman’s incredibly important to me, and that idea of cinema as a closeup, the landscape of somebody’s identity, and the invitation to try and go into the secret life of their thoughts is something that’s so important in his cinema.

I know we’re almost out of time, but I have to ask you about the score and working with composer Jed Kurzel. Jed’s work is absolutely exquisite, Benedict. I love the piano, a lot of single-note piano that adds a haunting essence to it. Just so well done.

The score is by Jed Kurzel. He’s a really old mate of mine. We’re both from the same town in Australia, both from Adelaide. He’s done a lot of incredible scores for different people. His brother Justin Kurzel, I used to work with in the theater as well. Jed did the score for my first movie Una and he’s also done the score for several theater productions of mine. We faced a kind of real challenge with the movie to have very evocative, emotional music, but at the same time to kind of talk of a thriller, and to lean into the kind of period elements while not being a nostalgic score. We wanted it to have a kind of contemporary urgency, but also to not feel like it was making simply a kind of period movie. There was this kind of beautiful deep cut in terms of the soundtrack, the Scott Walker song, or the “Blood of an American” track, or the Nina Simone song at the end, that are all really emotive songs. They’re not period clichés. They offer a kind of new look on the period, and the turbulence, and the emotion of that time. I’m sure he won’t mind me saying, but obviously a key movie for us was The Conversation and that David Shire soundtrack in that which take those jazz motifs and make them so haunting. That was something that we worked with a lot. And that’s full credit for Jed for sort of overcoming a kind of tempting influence from one of the great soundtracks of surveillance movies and absolutely making it his own and making it speak in a new way.

by debbie elias, exclusive interview 02/18/2020