The time is 1995. The world is connected by landline telephones. As director Gillian Robespierre explains, “It wasn’t that easy to communicate with people. When you call them on the landline and made a plan, you’d better be on that corner [for a ride] or else you’re stranded. I think we called it LANDLINE because that was our lives. Everything was built around this phone and it was our only form of communicating.” And communication, and the lack thereof, is what LANDLINE is all about as told through the eyes of an average middle-class family in Manhattan.

In 1995, there were still an abundance of brick and mortar record stores and book stores. Starbucks hadn’t taken over the world. Internet was in its infancy and not yet found in homes. Cell phones were big clunky things and you’d only find them with doctors, lawyers and the 1%. If you didn’t have a phone in the house, or were using a payphone, other than for the postal service, the only other method of communication was in person. But without the immediacy and security of a digital wall, face-to-face confrontations and communication were the norm. And that norm, as it has for hundreds of years, often sets the stage for irritation between people and in this case, characters, forcing people to listen to each other whether they want to or not.

Meet the Jacobs family. Sisters Dana and Ali, and parents Alan and Pat. Dana is in her late 20’s, engaged to nice boy named Ben with whom she lives, and she works in the magazine industry. Ali is 17 and a senior in high school. Finding her footing in the world be it with her peers or her family, there is plenty of angst as Ali pushes almost every envelope possible that a 17-year old can push as she tests the waters of impending adulthood. She sneaks out to raves, tries drugs at the insistence of her best friend, sneaks away to the family vacation cabin to have sex with her boyfriend for the first time, and battles her mother and father at every turn.

As for Pat and Alan, Pat idolizes Hillary Clinton and in the workplace emulates Hillary right down to her shoulder-padded, wide-lapeled Nolan Miller-esque suits. She vocalizes her opinion at every turn and on every subject be it at work or at home, but at home, she drops the “F-bomb” as often as one sits down to a cup of coffee at breakfast. And she battles constantly with Ali. Alan is always toiling and slaving away at an advertising firm while dreaming of becoming a playwright. While his intentions seem honorable, one can’t help but sense a total disconnect with what’s happening in his own house so when forced by Pat to discipline Ali for sneaking out of the house, is not only surprised at what Ali has been doing, but can’t think of how to discipline her. The only obvious answer becomes to rip the phone out of the wall.

Needless to say, the sisters are as different as night and day, and thanks to an approximate 15-year age gap, also seem to have a generation gap happening which leads to constant sibling bickering. Ali thinks Dana has the best life with a sweet fiancé, impending marriage and a career. Dana holds a grudge against Ali because of all the things Ali does that Dana thinks she gets away with when Dana didn’t. Ali gets to sneak out. Dana didn’t. Ali is drinking and trying drugs. Dana didn’t. But all that feuding stops when Ali in a somewhat drunken and drug-induced stupor stumbles onto a floppy disk which on inserting into the family computer discovers hundreds of erotic (almost pornographic) poems written by her father to someone he only refers to as “C”. Convinced her father is having an affair, Ali confides in Dana as to her discovery. And while Ali is confiding in Dana, turns out Dana has something to reveal to Ali; she’s having an affair with a hunk of a guy she new in college. Dismissing her own infidelities, Dana teams up with Ali and the two set out to uncover the identity of “C” before confronting their father and telling their mother what they know.

Gillian Robespierre and Elisabeth Holm are a magical team. Their sensibilities and storytelling methods are similar and in the case of LANDLINE, stem from the same experiences. As co-writers, the two stumbled onto the theme of LANDLINE as they talked about their lives and how they grew up, and most importantly, how their parents divorcing was different than what one sees in the movies today. As Robespierre relates, “Our parents told us that we were getting divorced. Our families didn’t implode; well there was some obvious implosion, but what happened after that was that we grew closer. Our parents became human. They weren’t just these people forcing rules down our throats. Our mothers became these very vulnerable, strong women. They were always strong but for the first time ever, vulnerable, and let us into their inner dialogue and thoughts. Our older brothers became friends and not just these weird uncle types that were sharing a room with us. It was so cool that Liz and I had that shared experience. . .So we wanted to take that narrative, the divorce one, and sort of flip it on its ass and, we knew early on that we wanted the main focus and who we were following were three generations of women within one family and how they dealt with this ‘tragedy’, how they communicated with each other, how there was a communication breakdown within the whole family structure, and what makes them be put back together is this rustling of the nuclear feathers. That’s sort of where it started. And then it just became very clear early on that we wanted to do it in the 90’s because it happened to us in the 90’s. It started with our personal story and then it became something else.”

Staying true to the core idea of a family being forced to communicate, a family that had trouble communicating, had trouble being honest, and had lots of secrets and lies and privates lives happening, Robespierre and Holm take us on the journey of a family coming together and getting to know one other a little more honestly, and without texts, social media, or reading somebody’s email. They make the characters talk to each other. And they make the characters fully three-dimensional so they are relatable and resonant on multiple levels.

With a simplicity in the manner of storytelling, Holm and Robespierre allow the messiness and complications of life and being human to propel the story forward while maintaining a female perspective and point of view, much of which comes from Dana’s own self-psychoanalysis and finger-pointing at Ali.

The result is a sense of timelessness, a timelessness of story, character and human nature, that is so solidly told that it doesn’t take long before one forgets there are cell phones, no electronics. They allow the audience to become so absorbed in the story and the film that if any kind of social media or electronics beyond the old computer had been introduced it would have destroyed the unfolding human interaction. It’s a refreshing change of pace.

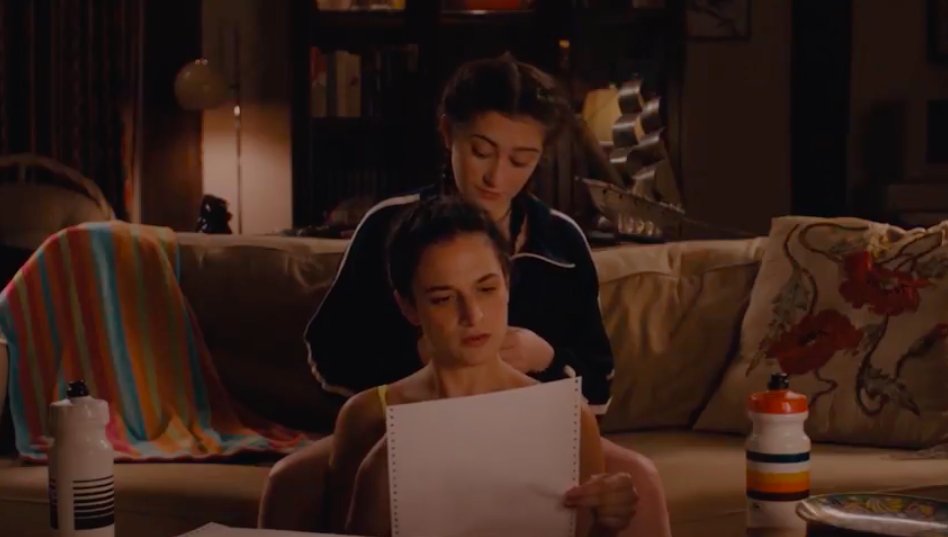

Reteaming with Jenny Slate who starred in the Robespierre-Holm work, “Obvious Child”, Slate IS Dana. Her sense of timing and delivery is perfection. Slate runs the emotional gamut from an ebullient successful woman who has it all to one who falls from grace thanks to self-doubt and even attempts at self-destruction. Slate easily navigates the bonds of romance, infidelity, sisterhood and the all important mother-daughter dynamic with a believability and confidence.

The real joy of LANDLINE, however, is Abby Quinn. Talk about a delight! Talk about a performance! In her first major leading role and going toe-to-toe with Jenny Slate, Edie Falco and John Turturro, as Ali, Quinn is a standout. Not even born until 1996, she embraces the world of 1995 with a carefree effortlessness, perfectly capturing the emotion-filled teen angst that comes with peer pressure, impending adulthood, sibling rivalry and mother-daughter head-butting. There is an honesty to Quinn that comes through with every nuance, every movement, every vocal inflection. Keep your eyes on Abby Quinn, folks, as her star is on the rise.

As Pat and Alan, Edie Falco and John Turturro are poetry in motion as they spin the wheels of a stagnant marriage, almost living separate lives while living under the same roof, oblivious to each other, but cognizant of their daughters. Turturro gives Alan a sense of desperation that is palpable while adding a daddy-daughter gentility to the role. Falco is tough as nails and digs her heels in as mother, executive, and family commander in chief, yet when tragedy and truth strike, reveals a heartfelt vulnerability.

And don’t miss Jay Duplass who makes Dana’s fiancé Ben one of the kindest and sweetest guys around.

From a production standpoint, production values are high, starting with the visuals and editing. Editor Casey Brooks keeps everything fast paced, a little bit frenetic much like the family so that the editing mirrors the family dynamic right down to the end where it slows down a bit as communication lines are reopened.

And then there’s Chris Teague’s cinematography. The lighting and lensing is beautifully done. Notable is the difference in Teague’s design when viewed against his work on “Obvious Child” with Robespierre. Here we have cinematic texture, the grain of a 1990’s film, but then there is also a warmth. The apartment for the Jacobs family is lensed so that it creates a claustrophobic sense of everybody being on top of one another so they are forced to communicate, but still don’t. On the flip side, when we get outside, Teague and Robespierre go with wide shots which, again, mirror story as when individuals are outside of the home each is more inclined to communicate or open up to someone. From a New York street to the openness of the woods in upstate New York, lighting is natural, framing is wide. Standout is Teague’s lighting and close-up work in a rave scene involving Quinn’s Ali. Beautiful neon lights set against inky blue-black of a club interior, tighter mid-shots to close-ups.

Calling on Kelly McGehee for production design, while 1995 appropriate, nothing sticks out like a sore thumb. There is a comfort and ease to the production design that helps fuel the timelessness look of the film and appeal of the story. Joining in McGehee’s expertise is costumer Elisabeth Vastola.

Kudos to music supervisor Linda Cohen who delivers one of the most eclectic, and fun, soundtracks to come along in awhile. With everything from Paul Simon to 10,000 Maniacs to African dance music to the burgeoning hip-hop tunes of the day to Steve Winwood’s “Bring Me a Higher Love”, the music, for the most part, is familiar, but songs not typically used in films which, again, adds to the refreshing nature of LANDLINE.

Timeless and refreshing, tether yourself to LANDLINE.

Director: Gillian Robespierre

Writers: Gillian Robespierre and Elisabeth Holm

Cast: Jenny Slate, Abby Quinn, Edie Falco, John Turturro, Jay Duplass

by debbie elias, 07/17/2017