By: debbie lynn elias

Based on the real-life 1940’s murder spree of Martha Beck and Ray Fernandez, “Lonely Hearts” is nothing more than a poor man’s poor adaptation of Leonard Kastle’s intriguing and far superior 1970 “The Honeymoon Killers”.

Ray Fernandez is a sleazy con man making his way through life by seducing and swindling lonely, often wealthy, women. Using “lonely hearts club correspondence” much as we now use the Internet for dating today, Ray’s come-on is his being a sexy Latin lover. Enter Martha Beck, an overweight (although not so depicted in this film), slovenly and mentally disturbed woman with a penchant for obsessive kinky sex and love of money that rivals that of Ray, turning his potential mark into his partner. Head over heels in love, the two improve on Ray’s scam by having Martha pose as his sister with the two running a tag-team operation. Due to Martha’s jealousy, derangement and insatiable lust for murder, the pair now narrow their victims to primarily older affluent spinsters and widows. Taking money, jewels, savings and anything else they can get their hands on, Ray and Martha end each con by murdering the woman in what investigative evidence determines to be a bloodied sexual frenzy.

Detective Elmer Robinson is bereft with grief following the suicide of his wife, ironically after she decorated a cake celebrating their wedding anniversary. A bit slow to get back in the saddle again, Robinson gets a kick in the butt when a case he had become obsessed with (as did most of his cases in the 40’s and 50’s) yields some inexorable new evidence concerning the unresolved deaths of women who answer lonely hearts club ads. With his partner Charles Hildebrant, the two start working the case only to discover some similarities between the suicide of Robinson’s wife and that of a 25-year old “lonely hearts” club member found blood-soaked in a bathtub. With revenge in his heart and clues jumping out from every direction, Robinson and Hildebrant start to put two and two together. These aren’t random suicides. These are murders; murders that bear the stain and stench of Beck and Fernandez.

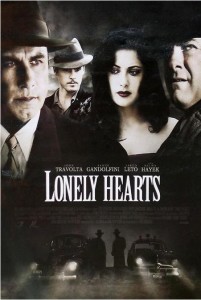

John Travolta and James Gandolfini unsuccessfully take on the roles of Robinson and Hildebrant. With ridiculous toupees and attempts at testerone-filled doe-eyed weepiness but with an hardened edge, the two are laughable. Despite auditioning over 400 actors for the part of Elmer Robinson, director Todd Robinson has only choice, John Travolta, and held out on the project until Travolta’s schedule permitted his involvement. That was a mistake. Travolta’s interpretation of the brooding work-obsessed Robinson is stiff and almost robotic at points, perhaps due to the character’s lack of dialogue, which is Travolta’s typical style, thus forcing him to texture the character visually. I can understand wanting to create the sense of being a fastidious, intent, distant, workaholic with blinders so tunneled that but for your work, the world itself is blocked from heart and mind. Travolta, however, is so forced and so stilted so as to be cardboardish, and with that toupee, cartoonish and unbelievable. James Gandolfini, while not as disappointing and unconvincing as Travolta, is fine with the basic mechanics of the Detective, but in his role as Robinson’s partner and friend and sole support system after the death of Robinson’s wife, is void of the sympathy and empathy one would expect to see between two guys as close as we are led to believe, giving a more cold and callous image that makes one wonder how Hildebrandt can be believed as the ship steering Robinson through his personal troubled waters. Likewise, as Fernandez, Jared Leto fails miserably as the Latin lover and garners laughter thanks to bad prosthetics. One joy is Salma Hayek as Martha Beck. Although the complete opposite of the real Martha Beck (obese, plain, dowdy with an obsessively disturbing psychotic ugliness to her), Hayek is not only psychologically compelling, but evocatively stimulating with alluring perfection personified.

Written and directed by Todd Robinson, the grandson of Detective Elmer Robinson, one would expect him to have stayed true to his grandfather’s legacy and not manufacture unresolved plot points or stilt the characters’ person or personality. According to Robinson, “My grandfather was usually very quiet but when he told stories he was a great storyteller. He would tell stories about scams and scams that led to murder like in the case of Martha Beck and Raymond Fernandez. He told me about when he found the crime scene, they pulled up floorboards and underneath the wood everything was covered in blood. He immediately knew someone was murdered there, though there was no body.” Emasculating the true facts with fabricated “glamour” and intrigue, Robinson does nothing more than make a joke of these heinous crimes and diminish his grandfather’s efforts. Although the style and methods of the Lonely Hearts Murderers were exceedingly twisted, gory and violent, Robinson resorts to what looks like gratuitous acts of violence, graphically shows a myriad of murders – a pregnant woman poisoned by Ray, Martha shooting another woman while in the sack with Ray, an old man and his dog being shot, and the highlight, the 1951 executions of Beck and Fernandez by electric chair at Sing Sing. (Of note, electrocution had to be delayed. Due to Beck’s obesity, she didn’t fit in the chair.)

Different from the prior film versions, Robinson structures “Lonely Hearts” so as to give the detectives equal time and a louder voice than the killers which is a minimal saving grace to the film. Unfortunately, he fails to give any voice or compassion to the victims. Visually the film is stunning thanks to cinematographer Peter Levy. Saturated in tones of red and black, one’s eyes are forced to the screen. To obtain that film noir look of the 40’s, Levy used an antique suede filter and minimal camera effects, electing to use extremely specific close-ups and mid-shots as opposed to anything panoramic, all of which go far in creating tension and laying the foundation for the cat and mouse game of intrigue. Adding to the look is the impeccable production design of Jon Gary Steele who captures the very essence of 1940’s New York.

A valiant effort filled with technical and design excellence, overall, as a film LONELY HEARTS is emptier and more alone than the victims of Beck and Fernandez.

Elmer Robinson: John Travolta

Charles Hildebrant: James Gandolfini

Martha Beck: Salma Hayek

Ray Fernandez: Jared Leto

Written and directed by Todd Robinson. A Millenium Films release. Rated R. (108 min)