By: debbie lynn elias

There is little factual recorded history about the Mongols, let alone the man born Temudgin, who would later be known as Genghis Khan, one of the greatest rulers in history; the man who united all of Mongolia under one banner. The only known written Mongol history from the eras of conquest of Genghis Khan is a poem entitled “The Secret History of the Mongols. Written by an unknown author sometime after Khan’s death in 1227, the writing was considered lost until a copy believed to have been translated in the 14th Century was discovered in China sometime in the 19th Century. What makes this work significant is that is sparked a furry within Russian filmmaker writer/director Sergei Bodrov whose only prior readings on the Mongols and Khan up until the 1990’s was in schoolbooks, all of which portrayed Khan as a monster, in fact, so monstrous, that for over 60 years in modern times his name was not permitted to be spoken in parts of Russia. Always curious about this legendary ruler, Bodrov had initially stumbled onto a book by Lev Gumilev entitled “The Legend of the Broken Arrow”. Steeped in legend, the book details the history of the Mongols and the Turks. Fortunately for Bodrov – and us – the book inspired him to dig deeper still into the legend of Khan; the man behind the myth. Who was he? Where did he come from? How did he become Khan? And so Bodrov embarked on his hunt to learn as much as he could and bring Khan’s true story to the big screen. The result of Bodrov’s journey is MONGOL, an epic story of life, love, loss and loyalty, and a little boy named Temudgin who grew into the man history would remember as Genghis Khan and the woman who stood by his side from the age of 9, his first wife and most loyal advisor, Borte.

It is known fact that over the years, Temudgin often spent time in captivity, only to eventually be rescued by his tribe. During one ten year period, however, there is no fact, lore or legend for Temudgin’s life, seeming as if he vanished from the planet. Sergei Bodrov, agreeing with theories espoused by Gumilev, believed that it was during this time that Temudgin was, in fact, a prisoner somewhere in the Mongolian region and from this perspective and through use of flashbacks, tells Temudgin’s story. After all, when a prisoner, what is there to keep one going but their memories and reflections of life.

The time is 1172. 9 year old Temudgin is travelling with his father Esugei to the vicious Merkit tribe, sworn enemies of Esugei’s clan. And not just any enemies, but those with a personal vendetta against Esugei as he stole his wife, Temudgin’s mother, from one of the Merkit leaders. Under tribal custom, by Temudgin taking a Merkit wife, the tribes will “make peace.” But be it fortuitous or not, stopping along the way for food and shelter with a friendly tribe, Temudgin finds the girl he wants for his wife – Borte. 10 years old and full of fire and brimstone, Temudgin mandates that he pick his bride here and not from the Merkits. Selecting Borte, he promises to return for her when he is of age to marry and as a symbol of his promise, gives her his most prized possession, a wishbone with the power to bring her whatever she desires.

Sadly, on their way home, Esugei is poisoned and dies. And although leadership should be assumed by the young Temudgin, the power hungry Targutai seizes control of the tribe and all of Temudgin’s family’s possessions. A nicety among the tribes was an agreement that children could not be killed. Anyone seeking to spill their blood had to wait until the child was of a certain height, a fact which frustrated and angered Targutai as he needed to eliminate Temudgin, the rightful tribal ruler, before Targutai could be challenged and defeated.

Breaking free from his captors, the young boy takes off on his own adventure into the snow-covered mountains and steppes of the region seeking guidance from the spirits. Fortunately, Temudgin meets a friend in the form of Prince Jamukha, who comes to Temudgin’s aid. Their bond is such that they become blood brothers, swearing allegiance for eternity.

But freedom is elusive for Temudgin as Targutai tracks him down and captures him yet again. But again, Temudgin’s intelligence, strength and determination prove valuable allies and he escapes yet again. Managing to stay free from Targutai, it is not 1186 when grown into adulthood that Temudgin is again captured. Biding his time and with the wisdom of maturity, his wits and warrior instinct, he again manages escape with the intent on claiming his betrothed – Borte.

Difficulties abound as vengeful Merkits kidnap Borte leading Temudgin to call on his blood brother for help. And although tribal codes do not permit declarations of war for “wife stealing”, Jamukha nevertheless agrees to help Temudgin rescue Borte. Sadly, their brotherly love is put to the test as Temudgin’s sense of fairness to Jamukha’s warriors shifts alliances, shapes a people and a continent and devours the goodness of a 9 year old as Temudgin embarks on what would become decades of violence as he attempts to command the entire Mongolian and Asian region.

Although Bodrov desired an authentic Mongolian cast, particularly as to his principals, casting took place around the world. Ultimately, Japanese actor Tadanobu Asano was cast as Temudgin. Given the time period in the Mongol’s life depicted in this film, Asano is an ideal choice. With a dignified carriage and commanding demeanor, he also brings elements of humor and humanity to this man so long perceived as a monster. You are drawn to the character and it doesn’t take long before Asano has stripped away the mythological pretenses and bares the very real pain of a man.

China adds its acting contribution to this multinational undertaking with Honglei Sun. As Jamukha, he graces the film with humor. For Bodrov, this is key to the film. “The more difficult your story, put humor in…Humor helps.” And Sun adds a lightness with familial banter that is believable and humanizing. Critical to conveying Temudgin’s story, however, is Borte. With two weeks to go before production, Bodrov still had no Borte. But at the last minute, his casting director found a non-actress; a complete unknown – Khulan Chuluun. As Borte, she is both enchanting and hard as steel. But it is the expressiveness of her face that speaks volumes. No sub-titles are needed in any scene with Chuluun. One look at her says everything. The real casting gem, however, is Mongolian born Odnyam Odsuren as the young Temudgin. He steals your heart and every scene.

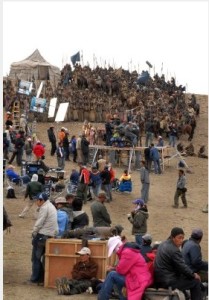

Written and directed by Bodrov, to call this film epic is an understatement. The story is fascinating not only for history buffs for just in the shear magnitude of the life of Khan. And no detail is overlooked when it comes to history (but for the missing 10 years) or the accuracy in depicting the time and the people. Shot over the course of two years with 25 total weeks of shooting, logistics alone would have decimated a lesser director. Demanding authenticity, locations were in remote locations in China, Mongolia and Kazakhastan – all lands that were part of the Mongolian Empire. Due to their being far from civilization (at least 12-15 hours), roads often had to be built to transport the crew of some 600 plus over 1000 extras (not to mention horses and livestock). Not relying on CGI but utilizing the available stuntmen and horsemen from the region plus those 1000 extras, battle sequences are impeccably choreographed and lensed with a heart pounding ferocity. Mid and tight shots capture the sense and strength of the Mongols and the ardor for battle pumping through their veins. If anyone ever had a need to release some aggression, this was the film to be in.

Compounding this massiveness was the daily drama of filmmaking with a few added problems I have never heard encountered before this, one of the biggest being food. “I brought some Russians [on the crew]. One day, they say, ‘We don’t want to eat Chinese food anymore. We want spoons and forks.’ 200 people said ‘we’re not working anymore. We’re on strike. We’re fed up with the food.’ I can’t send them home. I need them. 12 hours drive to the airport and then flight to Kazakhastan to bring forks and spoons for Russians. Every day there was something. [Then] you have 1000 extras and we have to train them. They came with their own horses. We have to keep them 4 weeks. But 4 weeks is not enough for the training. You have to keep them longer but they don’t want to stay. But we need them. Every day something was happening. There was no easy day.”

Calling on Dashi Namdakov for production design, Namdakov is from Buryat which borders Mongolia and serves as home to many Mongols. His inherent knowledge of the Mongols and their customs proved invaluable not only in the authentic sets, locations and costumes, but in paving the way for filming in towns practicing shamanism.

Calling on Dashi Namdakov for production design, Namdakov is from Buryat which borders Mongolia and serves as home to many Mongols. His inherent knowledge of the Mongols and their customs proved invaluable not only in the authentic sets, locations and costumes, but in paving the way for filming in towns practicing shamanism.

Critical to a film of this magnitude is cinematography and Bodrov had two of the best. Initially calling on Rogier Stoffers for the job, Stoffers lensed and lit the childhood portions of the film. But, when money ran out not halfway through shooting, Stoffers moved on to other projects and the following year when financing returned, he was unable to, thus turning the task over to the amazing Sergey Trofimov. A technical master, Trofimov ranks as one of my favorite cinematographers thanks to the vivid imagery of the battles of good versus evil in “Daywatch” and “Nightwatch”. And as luck would have it, the energetic style of Trofimov bode well with the sequences remaining to be shot in MONGOL – the sprawling battle sequences.

Given the tenor and authenticity of MONGOL, it comes as no surprise to me when I asked Bodrov had he watched any of Hollywood’s earlier movies about Khan before undertaking MONGOL. Hanging his head and shrugging his shoulders as if chilled, “I couldn’t force myself to watch them. . .They are laughable. ”

With a production to rival the armies of Genghis Khan himself, it is obvious that Sergei Bodrov was channeling the essence of Khan. From the hardships of filming to the fight for authenticity, as did his subject succeed, so does Bodrov, as he show us the man behind the mnoster with MONGOL.

Temudgin: Tadanobu Asano

Young Temudgin: Odnyam Adsuren

Borte: Khulan Chuluun

Jamukha: Honglei Sun

Directed by Sergie Bodrov. Written by Bodrov and Arif Aliyev. Russian with English sub-titles. Rated R. (124 min)