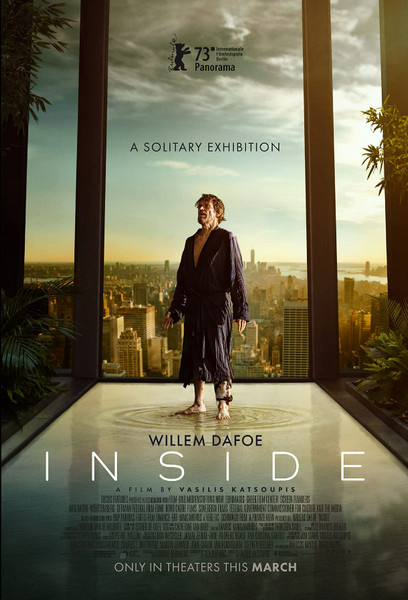

Is there nothing that Willem Dafoe can’t do? No character, no situation, no emotion in which he cannot immerse himself with believability, resonance, and fascination, drawing us into the world he inhabits or creates? In short, no. I always knew it was true but seeing his latest performance as Nemo in INSIDE, an art thief trapped inside a penthouse apartment and left to his own devices for survival, and entertainment, my belief was more than solidified. But with INSIDE, it’s not just Dafoe that drives the film but the vision of director Vasilis Katsoupis. Allegorical. Existential. Riveting.

An utterly enthralling and fascinating film, INSIDE is an intense introspective character study with two characters, Dafoe and the penthouse itself, while tacitly commenting on value; what does one value in life; what is the worth of a man? Using the setting of an art collector’s penthouse in which an art thief is “imprisoned”, gives great pause as to man’s valuation of the world around him and of his own life. There is also exemplary tacit visual commentary on the art world as a whole that speaks to how man values art versus valuing what goes into making the art.

Nemo is an art thief and apparently a very good one – until he’s not. We first meet him breaking into this Manhattan penthouse apartment which by design is cold, sterile, and stark but for some carefully displayed art pieces, be they paintings, sculptures, bronze works, etc. With a man on the outside, Nemo’s goal is clear; find three specific items, the most important piece being an Egon Schiele portrait, and get out. Unfortunately, he can’t find the Schiele and while searching (and meandering, gazing over all of the pieces within the home), the security system malfunctions. Nemo can’t get out. And because the system has malfunctioned, his men on the outside can’t – or won’t – try to rescue him. He is trapped. It takes a while though before he realizes that no one is going to come back for him – ever. His only hope is for the owner or staff person to return to the penthouse, but that seems bleak at best given Nemo’s extensive research giving rise to the theft and its timing.

Written by Ben Hopkins, the script is well structured with very minimal dialogue as the film is contained within the penthouse and the only individual present being Nemo for the better part of a year. In the second half of the film, we have a respite from “just” Nemo when he starts watching the closed circuit television which is trained on limited areas of the high-rise apartment building itself and allows Nemo to fantasize about Jasmine, the maid he sees cleaning the floors outside the impenetrable doors of his fortress. The film is taut and fraught with ever-escalating tension as the vastness of the penthouse becomes more and more claustrophobic with the passage of time and the absence of food, water, and even working toilet facilities.

Observational by design, it is Dafoe’s performance and emotional expressiveness through physicality and facial expression that drive the film while the cinematography of Steve Annis crafts the character of the penthouse and sets the visual tone. The cinematography is stunning and celebrates Thorsten Sabel’s impeccable production design and metaphoric hard-edged labyrinth nature of the apartment.

Normally, I would take issue with the number of ECU’s used by Annis to visually tell this story and design the visual tonal bandwidth, but with INSIDE it is not only appropriate, but necessary. As time passes and the luxuries of canned pate and caviar come to an end with desperation and innovation setting in as Nemo realizes he must find water and food as well as tools that can be used to help him find a way out or create some kind of exit, the camera hones in on each item within the penthouse with the type of scrutiny a collector would magnify and examine rare coins or stamps. The visuals raise the question, is this of value to Nemo? How can he use it? It is truly fascinating to watch this now tale of survival unfold.

Nemo’s prison is muted shades of bluish-grey cement with the only color coming from paintings, the greenery of an indoor garden which Nemo manages to keep going, and some very specific lighting notes. This is a world, and a man, filled with shades of grey. With no electricity after the “smart house” security system failure, natural light takes hold thanks to floor-to-high-ceilinged windows with pops of emergency lighting in a few key areas of the apartment. Natural light is beautifully apportioned and we feel the passage of day into night into more days, weeks, months. We see the seasons change and the grey notes of the sky outside. Shadowing is well done, particularly with Nemo’s corresponding physical and mental decline. But through it all, there is light to be found, literally and figuratively, much of which, thanks to Annis’ camera has a museum-like staging to it making Nemo a canvas unto himself.

Particularly effective is Lambis Haralambidis’ editing. Pacing is deliberate in not only creating tension and frustration but in allowing us to feel the passage of time, the slowness at which day-in/day-out monotony and loneliness take hold. We feel Nemo’s increasing desperation in the pace of the film and yet, as the film nears its end, a perfect blend of a widening camera and steady edit give us light at the end of the tunnel.

Directed by Vasilis Katsoupis

Written by Ben Bopkins

Cast: Willem Dafoe, Eliza Stuyck

by debbie elias, 03/21/2023