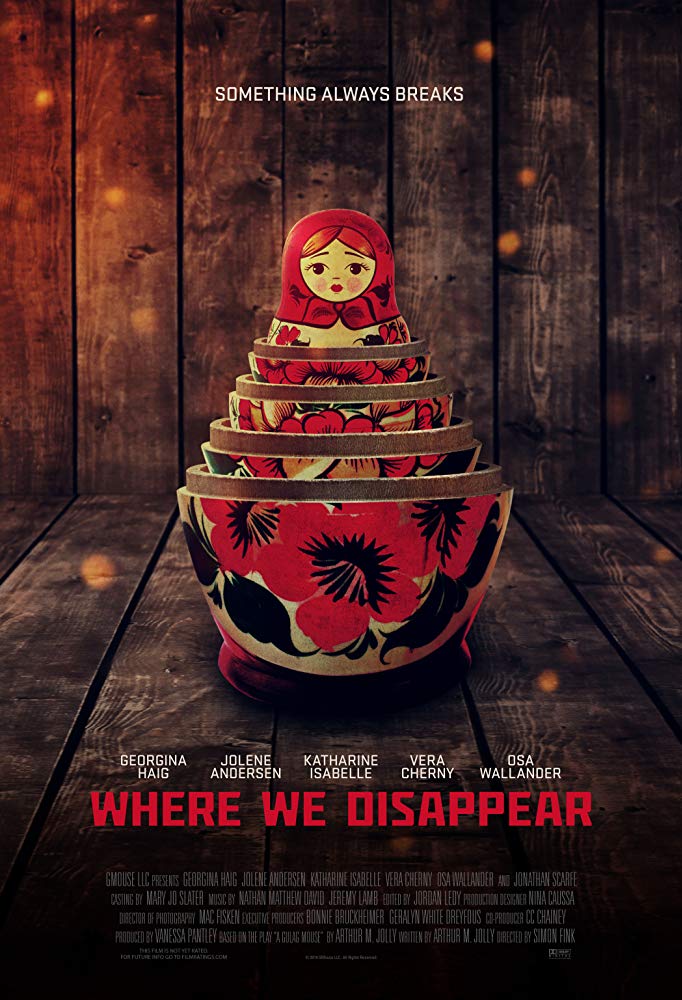

Adapted for the screen by Arthur M. Jolly from his acclaimed stage play, A Gulag Mouse, first-time feature director Simon Fink adroitly translates from stage to screen while keeping the story contained within one basic set – a Siberian gulag bunkhouse circa WWII era. Framed around five women sharing the bunkhouse, each imprisoned for various reasons, the story told is one seen primarily through the eyes of Anastasia, the newest “resident.”

Incarcerated for the death of her war hero husband on his return from the war, Anastasia’s pleas of self-defense and escape from his abuse towards her and her young son fall on deaf ears both with the authorities and her new roommates. Frightened, naive, and unfamiliar and inexperienced with the ways of the world, Anastasia’s fear is palpable. But what is more fearful? The gulag? Her roommates? Or herself? The answer may lie in this first fateful night in her new “home.”

While beautifully staged for the screen by Fink, having read Jolly’s play for the stage, a sticking point with this cinematic adaptation comes with the dialogue. Not only does it not feel natural in its delivery, but it appears that Jolly was a bit too precious with his words in retaining them in the adaption. Standout, however, are key monologues for each woman which are only elevated by passionate performances from some gifted actors. Particularly striking and effective is the monologue on sacrifice, survival, and lambs to slaughter given by Jolene Andersen’s Masha.

Performances are solid and given the distinctly different personalities needed for each character, casting is very well done. Georgina Haig is standout as Anastasia. Her wide-eyed facial expressiveness that ranges from fear to defiance is telling, adding to the arc of the character. Although the character of Masha is rather despicable, Jolene Andersen’s performance is rock solid – and very theatrical. Vera Cherny brings a beautiful naivete to the “mousey” Prushka while Osa Wallander provides an often pragmatic viewpoint on life in general, everything breaks, especially people. Katharine Isabelle serves the story well as Lubov, the “pretty one”, a woman who trades favors and food for the bunkhouse with a guard named Yuri.

The singular problem with the performances, however, comes with accents. This is one film where accents are important for immersion into time and place and for character believability and resonance. While Georgina Haig is from Australia, we don’t hear that inflection, but what we do get is a stilted cadence that goes in and out of what might be someone trying to speak English versus a European language. The others, Jolene Andersen, Katherine Isabella, and Vera Cherny all suffer the same plight. Osa Wallander, however, is perfection with dialect and attitude as Svetlana.

Mac Fisken’s cinematography is superb in its design and execution. Camera is fluid, moving around the single room as if giving it life. Lighting within the bunkhouse and the play of fading to the shadows the further from the stove and a single lightbulb one gets, fuels the idea of fear of the unknown and the darkness of the world the women are now in, while still shining a light on each woman. The golden tones punctuated with a light sepia wash are beautiful. Contrast with the nighttime escape (a gorgeous saturated inky blue-black) is stunning. Framing is very well done as he keeps the frame tight in this somewhat claustrophobic space while still finding moments to open up the lens to create a metaphoric emotional distance and view of life between each woman. Coverage shots are limited, which is preferable here as we see the reactions of each woman in the same shot. A few close-ups on faces in intense moments are very effective. Extreme close-ups are limited to objects – a gun, a knife, a shiv, a scrap of food. Adds a chilling fear to the mix.

Costume design is telling thanks to costume designer Megan Spatz. Given that in a gulag you essentially wear only the clothes on your back you arrived in, close inspection shows not only the walk of life from which each woman came, but gives an idea of the length of time each has been incarcerated. A faded print housedress adorns Svetlana. Bundled tatters cover Prushka. Masha seemingly fades into the woodwork and muted light in beiges while her persona takes center stage with rage and violence. Anastasia with her Jean Harlow-colored hair cowers under a winter coat with a blue handknit hat covering part of her hair. She shows style.

What is most intriguing is the structure of the story and the character of Anastasia. Given this is essentially her POV, the third act fascinates and prompts discussion and interpretation when it comes to Anastasia’s staging an escape. Out in the inky night amidst a dark forest and white snow glistening in the moonlight, she is speaking to a young man. As she speaks, Fink cuts to moments of each woman in the bunkhouse causing one to posit, were these women real or are they all parts of Anastasia created within her mind as a survival mechanism? Did she imagine these other women? Were these women real? Did she sacrifice them one by one in order to survive? Or was she the ultimate lamb, sacrificing her mind in order to remember her past and her son whom we last saw as a young boy at the train station awaiting for his grandfather? This stays with you long after the curtain falls.

One thing that proves to be an annoying oversight is the lack of visible breath, particularly when outside. We’re freezing in a Siberian gulag, but no one has visible breath?

The score is subtle, allowing the dialogue and character interactions to take center stage. A sad irony comes with the playing of Tchaikovsky’s “Sleeping Beauty Waltz” by a guard who is either ready to rape or “seduce” Anastasia.

Directed by Simon Fink

Screenplay by Arthur M. Jolly based on his play A Gulag Mouse written by Arthur M. Jolly

Cast: Georgina Haig, Jolene Andersen, Katherine Isabella, Vera Cherny, and Osa Wallander

by debbie elias, 06/19/2019