We all know the public story of Anne Frank and her family, thanks in large part to Anne’s diary. First published in its original Dutch in 1947, following publication by Doubleday of the English translation Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl in 1950 and thereafter in 1952 by Valetine Mitchell in the United Kingdom, Anne Frank’s story swept like wildfire throughout the world spawning plays, an Oscar-winning film, and with translation in more than 60 languages, it falls just shy of the Bible as being one of the most read works in history. Following Anne Frank’s death from typhus while incarcerated at the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, Miep Gies [a trusted colleague of Otto Frank who had helped the Franks, the van Pels family (changed to the Van Danns on the publication of Anne’s diary) and dentist Fritz Pfeffer (changed to Mr. Dussel on book publication)], who had found Anne’s diary after the Frank group was discovered by the Nazis and deported to concentration camps, turned the diary over to Otto Frank, the only family member to survive.

Thanks to Anne’s diary, we not only know a personal intimate perspective of the unfolding Holocaust, of the yellow stars, of Hitler’s rabid beliefs that permeated an ever increasing Nazi-occupied Europe, including Holland where the Franks were, but also a young girl’s hopes and dreams for not only herself, but the world. We also know what happened to Anne Frank, her sister Margot, her mother and her father, the latter whom survived the concentration camps and went on to spread the word of tolerance and tell Anne’s story until his death in 1980. But what most of us don’t know is the first chapter of the life of Anne Frank; the happy carefree life of a young girl; and then, the efforts to which Otto Frank went to save his family from the Nazis. The Anne Frank story didn’t start with her diary and going into hiding. It started long before, and continued long after, something that we discover in this stirring documentary from Paula Fouce, NO ASYLUM: THE UNTOLD CHAPTER OF ANNE FRANK’S STORY; as timely and topical today as in 1941.

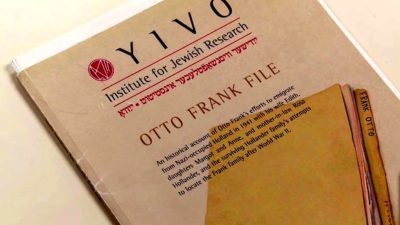

Approximately 10-years ago at New York’s YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, an archivist discovered a multitude of letters written by Otto Frank in 1941. The letters began with simple requests for assistance in helping the Franks emigrate from Holland to a “safe” country before Nazi occupation consumed the life and the lives, Otto Frank held so dear. But as the clock ticked down and it become more and more dangerous for Jews in Europe, Otto’s letters became increasingly desperate and pleading. It is these letters that set the stage for writer/director Paula Fouce and co-writer Michael Flores to tell the story of NO ASYLUM; a film as timely in today’s geopolitical climate as the original events in 1941.

Essentially breaking the documentary into three acts, Act One serves to present historical facts interspersed with Otto’s letters, giving us global geopolitical context, while the letters personalize his experience and his frustration with not only the situation in Europe, but with the rest of the world in their “turning a blind eye” to what was happening. It also tells us of his love for his family. From there, we move into interviews of family, friends and survivors, starting with the Frank’s cousin Buddy Elias and Rebecca Siegel. As with each of the interview subjects, the majority being survivors, they touch the heart as they speak. With both the pain and horror of the war and the death camps, and the wistfulness of happy childhoods playing in the street “when all the children would come out and play together”, you are in the moment with them. Particularly effective are the interviews with Siegel and Irene Butter, as well as Anne’s step-sister Eva Schloss. Eva’s mother eventually married Otto frank after the war ended.

As the chronology unfolds (and it is done exceedingly well) we are given an amazing timeline, albeit one of sadness, and in the case of the July 1, 1941 US mandate changing VISA procedures, a horrid take on our then Secretary of State and Congress. A back and forth of letters between Otto, Nathan Strauss and Julian Hollander, as shown through a very keen editing process by Michael Flores, is extremely powerful. As if the contents of each letter when viewed in the correct chain isn’t heartbreaking and infuriating enough, the editing is sharp, quick, tension building. You feel the urgency of “time running out” for Otto and his family.

Fouce and Flores also look to historical and religious experts who provide observation and commentary that “the whole world conspired to enable destructing of the Jewish people”. One is stopped dead in their tracks on hearing those words uttered.

As Fouce seamlessly moves into Act Two, there is more focus on Anne’s diary, as well as some poignant and sweet film footage of Otto Frank himself. But this is where the interviews of holocaust survivors really take hold as Irene Butter talks about the cattle cars. The specificity and detail of the memories, the time the cars would pull in on a Saturday and sit until Monday and then soldiers would read off names of people and herd them in the cars – shocking. But then Fouce and editor Flores interweave newsreel footage, (some of what was confiscated footage by the Germans) and still photos, making the words and the tears of these people even more moving, more poignant. Personal reminiscences of Sal de Liema and his friendship with Otto Frank nicely tie back to Otto and his letters.

One of the real standout interviews in NO ASYLUM comes from British Major Leonard Berney [Note: Major Berney, who ultimately attained rank of Lt. Colonel, passed away in 2016). It was Berney’s troops who arrived at Bergen-Belsen on April 15, 1945, which is where Anne Frank died mere weeks earlier. Hearing him speak as to what he saw first hand as a young 25-year old soldier is chilling – the piles of corpses, pit of corpses; even during these archival interviews done decades later, in his voice you hear his still overwhelming puzzlement of how to feed and help 60,000 people. You’ll find yourself cringing and crying as Berney tells horrifying stories of people in the camp taking hearts and livers from the dead, cooking them and eating them. Another testament to Flores’ editing is the tie-in between Berney’s recollections and the humanizing stories of Irene Butter as she talks about herself and Hannah Lee Goslar bundling up clothes and throwing them over the fence of the concentration camp to Anne, only to have them stolen by another prisoner.

Anyone who survived the Holocaust or knew of those who were imprisoned at various camps may take some comfort in listening to Berney. It is clear that he took his ultimate job as being in charge of the “Displaced Person’s Camp” very seriously. You can hear a tone in his voice that feels like “take that you Nazi scum” as he talks of moving everyone three miles up the road to an empty German army camp in order to give them some housing and minor facilities. And you hear the sorrow and pain as he talks about disposing of the bodies in pits but again, great strength as he talks about making the SS prisoners dig the pits and dump the bodies. Unknown to many for decades, Berney aided many young Germans intent of going to Palestine by giving them food and water; as if he was trying in his own small way to right the wrongs of the world.

Significant from an historical aspect is what Berney did to document the horrors of Bergen Belsen. Very little has been heard about his efforts in bringing in British media and newsreel photographers to show the British and the world what they were fighting for. That gives us as much emotional context now as it did to offer up visual proof.

A real surprise, even for many historians, is a recording of Dwight D. Eisenhower as we hear his thoughts and predictions that the Germans would deny these atrocities ever happened. One is taken aback and caught off guard hearing Eisenhower himself talk about rounding up the Germans and taking them to Bergen Belsen to show them what they did, what their army did, what their politics did. This British-American sequence is some of the most striking pieces of historical information to learn in NO ASYLUM. But hand in hand with that is the fast forward to Barney Elias as we see him walk around Bergen-Belsen and the headstone for Anne and Margot and a VO about the genocidal killing that has continued. “Humanity never learns.” It’s exciting to see him continue the work of Otto Frank, talking to young people about peace, learning through Anne’s diary and through listening to those who survived.

As Fouce takes us back to Auschwitz and Otto Frank – and Anne’s dear friend Pieter – we see the first visual sign of hope in the film, metaphoric celebration as Fouce gives us a shining sun, a brilliant blue sky and vivid green tree leaves, and we hear how Providence smiled on Otto in the choice he made to stay the camp; to not leave with Pieter; and how the guard ready to shoot the Jews in firing squad fashion was called away, thus saving Otto and many others.

But as our hearts are filling with some joy, Fouce then discloses the fate of Edith Frank. Tapping into every possible emotion through the construction of NO ASYLUM, we hear from wistful survivors, grateful for their own salvation, but saddened at the thought “if so-and-so could only have held on a few more weeks”. Undeniable is the hope that each of these survivors had. They survived because they never gave up and always had hope even in the darkest hours.

The research and editing on the doc as a whole is beyond impressive. As mentioned above, Flores’ editing sets a pace, builds tension and hits every emotional beat, tugging on heartstrings while inspiring deep thought and reflection. The entire construct with archival newsreel footage and stills are so succinctly reflective of survivor interviews, enriching not only the historical context, but the emotional resonance. And what of Luciano Start’s score? The end title music is gorgeous while the score throughout is uplifting and haunting.

As Otto Frank himself says during an archived interview, “I only learned to know [Anne] through her diary.” And as we see a bright blue sky, streaming sun, green trees wafting in the breeze, we get to know not only Anne Frank, but Otto and his love for life and his family.

Directed by Paula Fouce

Written by Paula Fouce and Michael Flores