By: debbie lynn elias

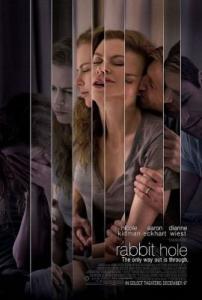

It is rare indeed to experience the adaptation of an excellently crafted and performed, emotionally impactful play, into an equally excellent film. Such is the case here with John Cameron Mitchell’s adaptation of the David Lindsay-Abaire drama RABBIT HOLE, the screenplay for which is adapted by Lindsay-Abaire himself. Not only equaling, but often excelling the emotional gravitas of the stage version, Mitchell expands the story beyond the four walls of a home, integrates nuanced characterizations and relationships, and plays with color, light and tersely dancing dialogue, housing all under a powerhouse performance from Nicole Kidman that, as we are already seeing, begs for not only accolades from the critics and public alike, but recognition with perhaps more than a few golden statuettes. Peeling away layer after layer of a couple’s existence 8 months after the death of their child, Mitchell ultimately lays them emotionally bare for all the world to see, with an understated elegance and complexity fueled by hope and rebirth.

Howie and Becca Corbett are your typical good looking, upper-middle class East Coast couple – a beautiful home, nice cars, tasteful understated clothing and mannerisms that give a sense of being “well off”, an impeccably manicured lawn and garden tended by Becca herself, elegant intimate quiet dinners for two at home often followed by quiet moments of reflection or reading. On the surface, their life seems perfect. But on second look, some of the veneer is cracked, allowing a glimpse into what lies beyond visible perfection. Although surrounded in the front yard by a white picket fence, the gate is always latched. The backyard resembles a “secret garden” with bowers and trees and hedges and a hidden gated door that is also locked, or is supposed to be. Looking out the front, beyond the street there is a lake, a river, completing the feeling of a medieval fortress. In the kitchen, there are a child’s drawings on the refrigerator. In the cupboard, sippy cups and insulated lunch bags with comic characters on them. Yet, there are no toys on the floor, no sounds of a child. And when Howie and Becca speak, it’s about the weather, ignoring a neighbor. Office water cooler conversation is more engaging and interesting than the conversation between them. There is a frigid distance between them; an empty hollowness to their relationship. And then we discover why.

Eight months ago, their son Danny ran into the street after his dog, was struck by a car and killed. Devastated, rather than bring the couple together in solace and comfort over their grief, Danny’s death has devastated them individually and as husband and wife, pushing them farther and farther apart with each passing day.

Howie wants, needs, to openly grieve for his son, but Becca does not. Howie wants to participate in group therapy, talk and listen. Becca does not. Howie wants to remember Danny with photos and videos. Becca has stripped the house bare of Danny’s photos. In fact, Becca wants to sell the house, move and start a new life. And now, on the 8 month anniversary, she has removed Danny’s drawings from the refrigerator and has begun packing up the things in his room, doing her best to strip Danny from her memory, ignoring Howie’s needs. Making things even more difficult is Becca’s mother, Nat, who herself lost a son some years back. Try as she might to help Becca, her efforts fall on deaf ears as Becca feels smothered and doesn’t feel the need to discuss anything. “I’m not you, Mom.” As we feel Becca’s pain and anger seething below the surface begging to explode, she is pushed even further to what has to be close to a breaking point, when her unmarried sister announces she’s pregnant. And then, as if by divine intervention, Becca sees Jason, a young teenaged boy, the boy who was driving the car that killed Danny.

This is truly an Oscar moment for Nicole Kidman. As Becca, she brings a cohesive range of emotion and incredible dry wit, concurrently nailing sarcastic one liners while evoking deep internal pain and vulnerability, all subtly layered beneath denial, sorrow and falsely placed ignorant bliss. The emotion is real, raw and honest. And although I hate to mention it, it was blissful to see Kidman’s facial muscles moving, to see brow furrows, laugh lines, small crows feet. She looks like a real person, a real mother, a woman who is emotionally torn and being eaten up inside. We see life in her eyes and with every line on her face. And it is beautiful.

Aaron Eckhart’s Howie is solid as he allows Howie to be visibly flawed, hurt and confused while retaining the sympathy necessary to propel the story. There are several exceptional emotionally charged scenes for Eckhart where he is mesmerizing, breaking the viewers’ hearts as we watch Howie’s break.

Interesting is the chemistry between Kidman and Eckhart. It’s very uncomfortable, very casual and off-putting. I never bought for a moment they were husband and wife, however, given the emotional estrangement of the characters, their pairing works well. Where both truly excel is in the conveyance of their grief and respective coping mechanisms. Their emotions are palpable, touchable and believable and never moreso than when each reaches their breaking point.

Particularly effective is the relationship between Kidman’s Becca and Miles Teller’s Jason. Incredibly dialed in and focused, teller touches your heart in a very dramatic way thanks to the great tacit sensitivity that he brings to the character. His scenes with Kidman are tender and gentle and although with minimal dialogue, it is crucial dialogue to the story. My only complaint about Dianne Wiest’s performance is not enough screen time. As Nat, she is wonderful, wise and at times, prolifically funny. Sandra Oh also compliments the cast as support group member Gabby, playing a pivotal point in the healing process of Eckhart’s Howie.

David Lindsay-Abaire’s story is very grounded; very honest and open. Already winning a Pulitzer for RABBIT HOLE, with this adaptation, he retains the very essence of what makes this an award winning story, but then combining his talents with those of director James Cameron Mitchell, gives us an adaptation that is extremely organic with a great natural flow and ease – much like the current of the river/lake that Becca and Howie look out upon every day. There is a silent truth and believability, connectability that good, bad or indifferent, pulls at the heart. Opening with Becca gardening, trying to “give birth” to a creation of her own – her garden – superb symbolism. One of the keys to the beauty of this film is the irreverent handling of grief. Never going for melodrama, Lindsay-Abaire and Mitchell humanize the characters with a delicate hand, allowing the actors to take center stage, letting raw energy flow as the cameras roll.

Frank DeMarco’s cinematography is crisp and beautiful yet minimalistic. Implementing a lovely color palette, thanks to lighting and Kalina Ivanov’s production design, striking contrasts are created that propel the various emotions and characters. There is a washed out yellowish sickly feel in the Corbett home for much of the movie with the only vibrancy found in Danny’s room. Contrastly, there is a stark clarity of exteriors and then the warming sun in park scenes with Becca and Jason which are exquisite to watch, adding volumes to the emotional palette.

A film adaptation that surpasses the excellence of the stage, RABBIT HOLE is a journey that is emotionally complex, candid and honest with an unflinching authenticity and genuineness of the human condition, topped off by a riveting performance by Nicole Kidman.

Becca – Nicole Kidman

Howie – Aaron Eckhart

Jason – Miles Teller

Nat – Dianne Wiest

Directed by James Cameron Mitchell. Written by David Lindsay-Abaire based on his play “Rabbit Hole.”