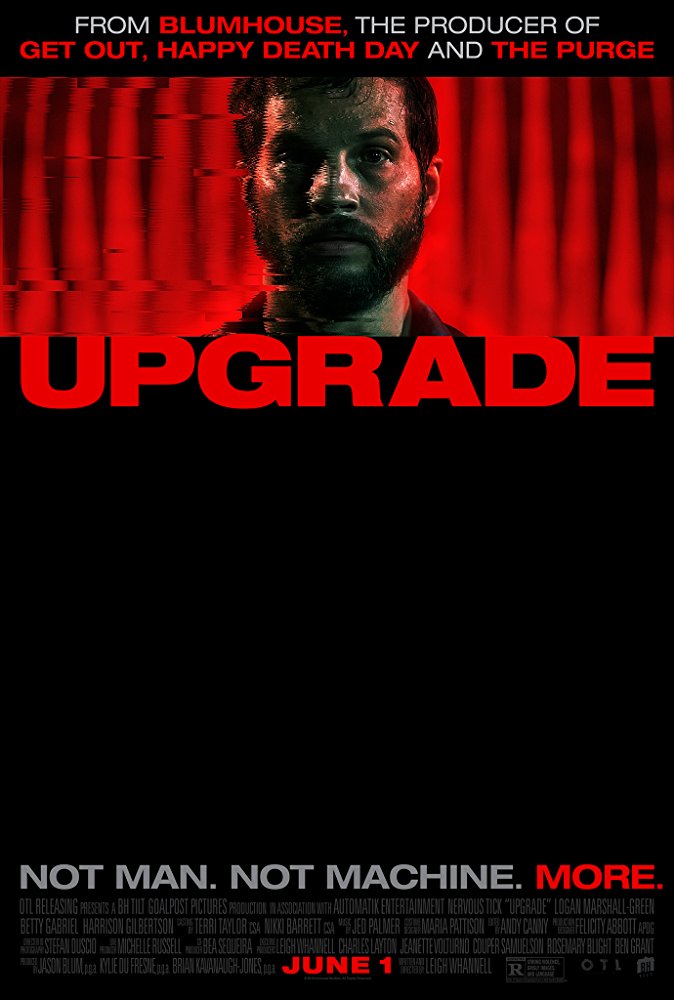

As comes as no surprise, writer/director LEIGH WHANNELL wows with UPGRADE! Best known to date as one of the creative forces behind the “Saw” and “Insidious” franchises, as well as playing the beloved “Specs”, right hand to Lin Shaye’s “further-delving” Elise Ranier throughout “Insidious” saga, Whannell now reaches further within himself, digging deeper into his own talents to pull out all the stops and deliver UPGRADE. Written and directed by Whannell, UPGRADE pushes the envelope not only with action but on a philosophical level in the ever-raging battle of man vs. machine.

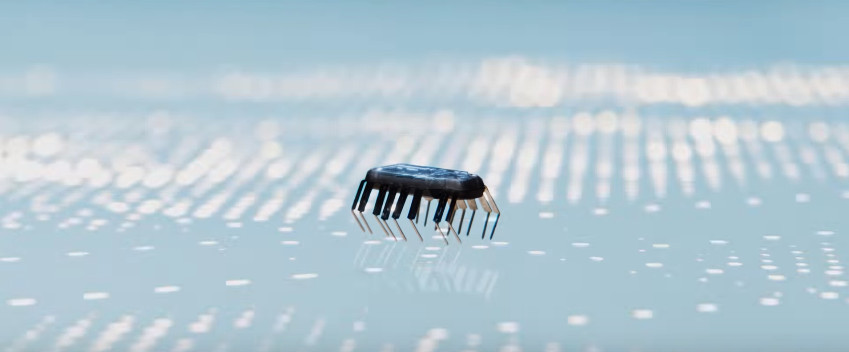

A mind-blowing cinematic experience, UPGRADE is not only a visual stunner with high polish and some lush production design thanks to cinematographer Stefan Duscio and Production Designer Felicity Abbott, but its Whannell’s story and conceptualization that is beyond exciting. Here we meet Grey Trace. A lover of all things old school living in a not-too-distant-world of computerized artificiality (and in many respects, the here and now), Grey accepts the hi-tech work of his wife Asha as part of existence, but for him it will never replace the sensory experience of getting your hands dirty with real work and a hands-on existence. Thanks to a brutal assault on the couple, Asha is killed and Grey is left a quadriplegic. But what if Grey’s physical functionality could be restored? What if he could be made whole again by the very technology he rages against? Approached by a genius billionaire who doesn’t look old enough to ride a bicycle let alone develop an artificial intelligence implant system known as S.T.E.M., Grey must face his darkest demons and fears. Does he remain in his paralyzed state or accept the technology that will allow him to seek vengeance against those who murdered his wife? And of course, everything has a price attached.

This ideology of man versus machine and their interdependence is beyond compelling and thought-provoking. Man needs machines. No matter how hands on one may want to be, you still need a machine in this day and age, be it a computer or a drone, or in the case of Grey – STEM, but where do you draw the line on integration and implementation. Where does the point become where man ceases to be man and becomes machine – be it through robotic surgeries and enhancements or simply by not using his own brain? Whannell explores this and more with a script that twists and turns and takes you down the rabbit hole with a full sensory experience.

Starring Logan Marshall-Green as Grey Trace, Harrison Gilbertson as computer genius Eron, and Benedict Hardie in a chilling “Hitler-esque” performance as militant leader Fisk, UPGRADE is a perfect blend of action, terror and sci-fi.

Always a pleasure, I sat down again with Leigh Whannell, this time to talk about his own directorial upgrade with UPGRADE. . .

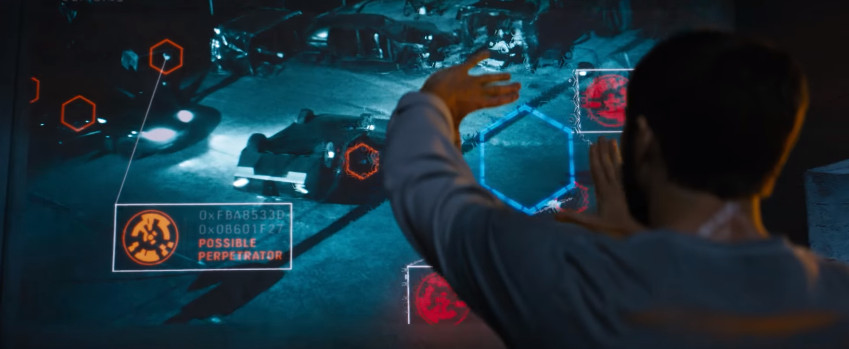

Leigh, My mind was reeling watching this. From the conceptional standpoint of man versus machine and the idea of where does the point become where man ceases to be man and becomes machine, be it from robotic surgeries, enhancements, or simply by not using his own brain? Then we get this great conceptualization that you follow through and develop with so many tangents and tiers that we get to look at. And you design your visual palette so perfectly so that it complements the ideology and story. And in addition to Stefan Duscio’s cinematography, you then have impeccable sound design. You use the same philosophy that if someone is blind, their hearing and other senses enhance. Here’s somebody who’s a quadriplegic, and then everything around him enhances with the color, with the sound. You left no detail overlooked.

Yeah. Yeah. He’s amazing, Stefan Duscio. That’s the thing you have to deal with, with a movie like this, where you’re being so ambitious and with the budget we had, your only hope of survival is planning, planning, planning, planning. I wanted to overcommunicate and overplan everything during pre-production. So Stefan, the cinematographer, and I, we had so many conversations about each scene and what the emotion of that scene was. We used it as an excuse to watch a lot of movies. We’d be in an office and I’d say, “You know, I want it to look like ‘SEVEN’ in that way that ‘SEVEN’ looked like a renaissance painting of something really ugly. Let’s watch ‘SEVEN’.” And the producer would come in and say, “Are you guys just watching movies or talking about the film?” But all that pre-planning pays off, which you then execute, because you know why you’re making each decision. You know why this blue or this person’s wearing this specific shirt or why we’re pointing the camera in this way. So it’s great to hear that you noticed it, and when you say the film is about man versus machine and how much of ourselves we give to computers, that really applies to today for me. It’s not even speculation about technology in the future. It’s about how much of our humanity lives in these things. I was just in New York and I was sitting there and I looked around, and literally every person around me had [cell phone] and was staring into it. I think it’s a full-blown epidemic. We’re putting so much of our humanity into and we curate these little second lives online with our social media accounts now. It’s a drug. So a lot of what this film is talking about is that modern problem, not even potential problems 30 years from now, but where we are right now.

With the reliance on technology and not using your brain.

Yeah. We delegate so much and we get so much of our emotions from these things. Those little hits of dopamine you get with “likes” and stuff, it’s a drug. I don’t know how we’re going to wean ourselves off it. I think our reliance is only going to increase before it decreases.

Something that I truly love in UPGRADE, particularly with the sound design, because it’s a cacophony of sounds, is that it’s layered so meticulously so that, of course, we have the sound of the muscle car, the humanity of man and old-school metal with that particular sound of the Trans Am as opposed to the sound of the police car or the sound of the computerized car that Asha has. Very distinct sounds, all differentiated, even when in same scenes. Then you have just the ambient sound of the drip of the waterfall in Grey and Asha’s home and also in Eron’s lair, because that’s truly how you designed that, as a lair. And you pick up the echo of walking on concrete. So all of these little things that are very tangible and very human set against this whole robotic undertone.

Yeah, and that’s so great that you noticed that because we were going for that. We wanted the tech in this movie to be imitating nature, and that’s really … The central theme of the film is the tech merging with us, becoming nature. And so, in the example of Aaron’s house, that lair we built, he has brought nature indoors. He has trees inside the house. He’s not going outside. He’s making nature come to him. I think that Felicity Abbott, the production designer, she and I decided early on that we wanted all the tech in this film to be trying to imitate nature. So, for instance, in the sound design that you talked about, I said I want all the computers turning on in this movie. I don’t want any blips and bloops like we hear in a lot of sci-fi. I said everything should sound like nature. In Grey and Asha’s house, when their computer screens come on, it’s the sound of rushing water, birds tweeting. Everything is trying to imitate the natural world, but it’s not the natural world. It’s almost like we’re digitizing the natural world to experience it without actually having to step into it.

Which is why with the sound design and the editing structure, it heightens it beyond what it would be if we were outside.

That’s good because you do that stuff in a sound mix, and when you’re sitting there in that room, you’re wondering, is anyone going to notice this? You’re going to put it in, but you don’t know. So to hear you say that it makes me realize that things that you put into the movie, no matter how small, are being received and processed and noticed.

It’s similar with the lighting design. I have to say I love how you and Stefan used spotlights, a lot of spotlights – spotlights coming down from the drones, spotlights on top of the operating room table, spotlight when Eron is showing off S.T.E.M., spotlights on the robotic arms in Grey’s kitchen. But you only use the spotlights when it’s artificial and robotic and technology. When it’s not focusing on that, lighting is more natural. Like you have the Trans Am in the garages. Natural, normal lighting. You go to the killer’s home where Grey is searching for information, and you’ve got the sun-kissed rays filtering through the drapes, kind of that filter but that golden glow behind it. Everything is natural. Wood tones and the light is softer. I love that visual distinction that you do with the lighting, and then you get to Old Bones and you throw in neon, and there, again, it’s a cacophony of visual tone.

Oh, thank you. That’s a great compliment. Stefan is a great cinematographer, and so we’re already working with someone who’s so good, and through our conversations, we decided we wanted the film, again, to be a mixture of organic and manmade. So the spotlights, as you said, are coming from the machines, but the natural world is trying to cave in on it, like vines growing in. It’s like I’m still here. Also, we love practical lighting, like lights that are in the scene. So instead of having a light up here lighting the scene, let’s have a lamp that’s actually a prop be a light. And so the machines allow you to do that with spotlights and let everything fall off. We loved playing with that. Any prop that someone talked to us about, we would try and figure out how that can light the scene, whether it’s the drone, as you say, being spotlit, or it’s a piece of tech. It just allows you to make the light part of the character, which I love that. I love seeing the light sources in the frame.

I think the last time I saw anything with light sourcing done this beautifully, Danny Boyle did it in “Sunshine.” All of the lighting was actually built within the spaceship, so it appeared to be natural lighting.

Oh, really? Interesting. I never saw that film, but I really want to.

You really should. There, again, it’s philosophical, thought-provoking, but visually with the design, they actually built in. It might have been Dod Mantle who did the cinematography in that, I can’t remember right now, but all the lighting was built within, so it was like an organic part of the ship.

Right, which you have an excuse for, because when you’re dealing with a spaceship, you get to invent. No one really knows what a ship of that era looks like, so you can put lights all up and down the walls. That’s great. I love that, too. It just allows the film to breathe more. I feel like when you can see the light the person’s using in the scene, it helps the film feel more real, connect with the viewer in a more instant way than a beautifully lit scene but you can’t see any of the light sources.

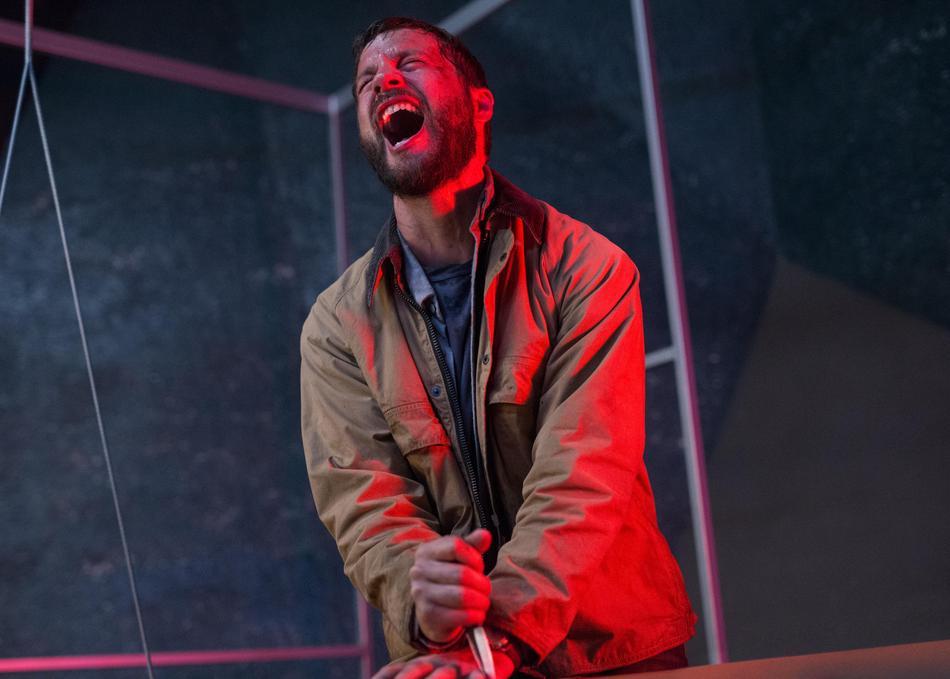

I have to talk about your casting, Leigh. Your casting is exemplary. You bring in Logan [Marshall-Green]. You see the distinction, the physical distinction, that he brings to the performance from before the injury to quadriplegia and then once S.T.E.M. is implanted and the robotic nature or the stilted nature of movement. He doesn’t have the natural flow body parts. How long did the two of you work on achieving that? Because it’s a constant reminder to us, especially when S.T.E.M. disconnects and all of a sudden he’s lying on the floor again, and he flops very naturally as a body does. But the physical distinction in his body movement is outstanding.

Full credit to Logan. He’s a very physical actor. He comes from the theater. He went to Julliard, so he likes working head to toe. A lot of film actors you talk to work here [indicates head and shoulders]. Logan wants to work right down to his toes. In this movie, he is the special effect. He’s not wearing an exoskeleton and he doesn’t have a high-tech piece of equipment strapped to him. It’s really just his body. I said that to him really early on when we first chatted on the phone because I had seen Logan in a film called “The Invitation”, which was a great low-budget thriller, and he played this character whose son had died and he’s carrying all this grief, and I thought, this is going to be great for this film. So when we first spoke on the film, I said, “You are the special effect in this movie.” He really took that to heart. Straightaway. I went to Australia to start pre-production. He was in LA emailing me videos of him in his backyard, moving. And I would send him notes. I would say, “Less Tin Man. Don’t robot dance, because you’re not a robot. Instead of moving like this, I want you to move like this . . . When the computer takes control, I want you to move with pure fluidity and grace. . . That control that a ballet dancer.” So he started doing that a little more, and then he got out to Australia a month before we started shooting, which isn’t a long time relative to what some movies do with training. So we just hit the ground running. He was in every day for a month, and we had him working with a stunt team, but we also had him working with a dance-and-movement coordinator, someone who’d worked for Cirque du Soleil. He was this stocky little guy, and every morning, Logan would come in at 5:00 and this guy would just have him moving, just getting his posture right. I remember Logan saying to me, “God, I never realized how bad my posture was until I did this movie,” because when the computer takes over, he’s sitting like this.

He has the most perfect posture in the universe!

Yeah. And if you look at his character before that scene, he made sure to tell that story, and he was kind of hunched. He was kind of a drawn-in guy, and all of a sudden, he’s opened up. So that was really fun doing that with him, and I think if I had someone who wasn’t good at the physical stuff, in hindsight, I would have been dead in the water with this movie because you’re so reliant on looking at him and understanding that story through the actor. Someone who didn’t pull that off, I think, would pull the audience out of the movie.

Then you bring in Harrison Gilbertson. I know his work from Scott Waugh’s “Need For Speed”, but here! This is the whole bleached-out “Dennis the Menace” hair and innocent, cherubic face. But there, again, the innocence and quiet and the palpable fright that he has is outstanding.

Yeah, Harrison Gilbertson. He’s great. [Eron] doesn’t know how to talk to people. His character, in my mind, has been raised to talk with computers. That’s what he’s comfortable with way more than humans. Even my daughter . . . My daughter can already operate my phone. She’s five. She can unlock it. I’m sitting there looking at her. She thinks it’s perfectly normal to walk into the kitchen and say, “Alexa, play the ‘Frozen’ soundtrack.” And Alexa says, “Playing the ‘Frozen’ soundtrack.” It’s amazing to me that what we grew up with thinking as science fiction my daughter thinks is just how we live. And so when I was imagining that character, I was thinking of someone who had grown up talking to Siris and was way more comfortable with that. You put an actual human being in front of him and he’s like, “Uh, hello.” Sitting down in front of a computer, and he’s like Mozart. He’s like a graceful concert pianist when he deals with a computer, but it’s human beings that [frighten him]. . . So it’s like a reverse … that electronic babysitter. That’s what I said to Harrison when he got the role. I said, “Listen.” I told him, “If you can, I want you to go away for two weeks.” He had a house down the coast of Melbourne and I said, “I want you to go there and not communicate with anyone except via email. So I don’t want you to speak to anyone on the phone or talk to them. Just email.” He’s one of those actors who’s so up for that. He was like, “Oh yeah.” He loves these challenges. I just wanted him to be someone that could not communicate with other humans.

And don’t think I didn’t notice your nod to James Wan in UPGRADE!

Oh yeah. Yeah, that was there. You noticed everything! Thank you so much. Really awesome! Thanks.

Now that this is totally done and is finally coming out to the world, you always take something from your projects. What did you learn about you in making UPGRADE that you’ll want to take forward into the future?

Oh, that’s a great question. You mean as a filmmaker or a human being or both?

Both.

Both. As a filmmaker, what I learned is that you can do ambitious things for a lower budget. There is a tendency to sometimes think that a movie of big ideas needs a studio tentpole budget. What I’ve found with this is you don’t have to just make the haunted house movie the family in the house or the drama with two actors in one room on a lower budget. The way we were able to achieve things just through hiring the right people . . . Felicity, who you mentioned, and Stefan. I give full credit to them. I wouldn’t take the credit “a Leigh Whannell film” on the movie in the credits because I said, and I’m not being falsely modest, I said, “So much of this movie is the crew.” I love them. [But] it’s not my movie. It’s all of us. I really mean that and stand by it. I realized that with these people’s help, we can actually make a film like this, which is good. And the reason I say do that with a lower budget is because I love the creative freedom of a lower budget. Once you start asking a big studio for 40 million dollars, you’ve got a lot of chefs and there’s a big committee around you, and they’re saying, “Okay. Page one. Don’t like this.” What I like is having that autonomy but being ambitious. To be honest, I think the biggest thing I learned is that I don’t like being away from my family for too long, because we shot this film in Australia and it was interesting. I said to my wife afterwards, I’m like, “God, I want to have this career, but how are we going to do this?” I want them to come with me, and that gets harder and harder as kids get older and school. So it is an interesting crossroads to be like, “Wow. I don’t think I’m cut out for this traveling salesman lifestyle, but that’s what I want to do with my life.” So maybe I need to talk to other more experienced directors who’ve done it and ask them how they’ve merged family and that life. I don’t know any really experienced, big [directors] . . . James[Wan] is one. He doesn’t have a family yet, but I know there’s other directors out there with families. So that would be an interesting question to ask them about, about how they merged the two. Tough one.

interview by debbie elias, 05/23/2018

RED BAND TRAILER